Reader's Choice

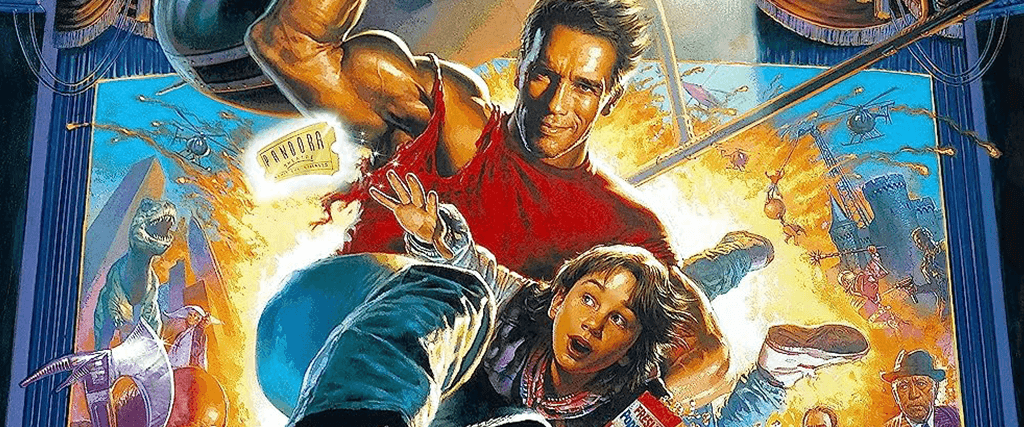

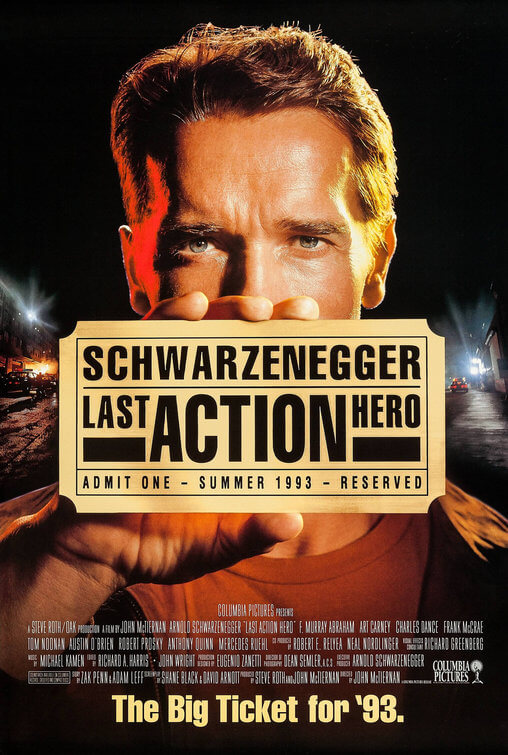

Last Action Hero

By Brian Eggert |

Somewhere between Planet Hollywood restaurants and Last Action Hero, Hollywood’s hubris spun out of control in the 1990s. Tinsel Town has always been self-referential and basked in its own glow. But in the ‘90s, its self-congratulatory nature got swept up in action-hero celebrity worship, boosting the likes of egomaniacs such as Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Jean-Claude Van Damme, and others into commercial icons who sold the general notion of Hollywood to the masses, as opposed to building the concept with quality storytelling. Released in 1993, Last Action Hero is a movie made by a committee—half a dozen screenwriters, studio execs, and Schwarzenegger exercising his star power—with each member having a different idea of what the movie should be. The outcome is hollow and messy. Whole scenes, lines of dialogue, and subplots don’t make any sense because of its many rewrites and rushed post-production schedule. Yet, there’s enough gloss and enthusiasm behind this ungainly product that warrants occasional admiration, though not enough to smooth out its lumpy, patchwork construction. In a shut-your-brain-off kind of way, it’s entertaining enough. But it’s more fascinating as a behind-the-scenes account of Hollywood’s worst impulse to engineer a self-satisfied blockbuster.

But let’s start by setting aside any extratextual factors that might shed light on why Last Action Hero is such a debacle and consider what’s onscreen. Inside a once-glorious New York movie theater, a plucky 10-year-old named Danny (Austin O’Brien) watches Jack Slater III, enthused by every action movie cliché. Embodied by Schwarzenegger, Slater is a cigar-chomping cop who doesn’t play by the rules. The opening scene finds him defying his ever-shouting Lieutenant (Frank McRae) to confront the axe-wielding Ripper (Tom Noonan) on the rooftop of his son’s elementary school. Danny eats this stuff up, having befriended the theater’s old projectionist, Nick (Robert Prosky), who invites the boy to preview the upcoming Jack Slater IV before its debut. Along with Looney Tunes cartoons, movies are Danny’s life and, doubtlessly, a coping mechanism to escape his home—in apartment number “3D” no less—where his concerned single mother (Mercedes Ruehl) tries to keep him in reality. But after a home invasion, where the intruder handcuffs Danny in the bathroom, the boy is desperate for an escape, though he’s full of cuts and bruises from this curiously never-again-addressed attack.

What happens next might be magic or, as I suspect, the delusions of a boy who consumes too much media and is grappling with the trauma of a home invasion. Either way, Nick gives Danny a golden movie ticket, which he acquired from Harry Houdini, though its origins stem from a series of Orientalized mystics in India and Tibet. The ticket allows Danny to enter the movie world of Jack Slater—a Looney Tunes environment full of ACME dynamite and cartoon violence, where, when Slater blows up, he’s left blackened with soot, but not dead, like after a bomb blows up in Daffy Duck’s face. Entering Slater’s precinct, the movie’s playful energy deploys cameos by Sharon Stone and Robert Patrick as their characters from Basic Instinct (1992) and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), respectively. Inside, the LAPD seems to employ anonymous, skimpily dressed female cops whose outfits look like rejected designs for a futuristic Madonna video, complete with their cone bras and vinyl. The LAPD also employs a cartoon cat voiced by Danny DeVito. Although Jack Slater IV is supposed to be a parody of Hollywood action movies, the film-within-the-film looks like no actioner we’ve ever seen (except, of course, Last Action Hero).

Accompanied by Danny, Slater attempts to locate mobster Tony Vivaldi (Anthony Quinn), the killer of his “favorite second cousin” (Art Carney). But it’s Vivaldi’s top henchman Benedict (Charles Dance), sporting a flashy glass eye gimmick, who learns about Danny’s magical movie ticket and eventually brings other movie characters into Danny’s real world, Ripper among them. Along the way, the tongue-in-cheek humor finds Danny quipping about Schwarzenegger’s catchphrase, “I’ll be back,” and making several references to Amadeus (1984) because he recognizes F. Murray Abraham, who plays a corrupt cop. There’s even a sequence involving Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), where Ian McKellen plays Death emerging from that film. But amid a mobster named Leo the Fart, Quinn’s downright silly performance, and no end of cameos (including digital renderings of Laurence Olivier and Humphrey Bogart), the movie scrambles the viewer’s brain with its nonsensical hodgepodge of metatextuality.

Accompanied by Danny, Slater attempts to locate mobster Tony Vivaldi (Anthony Quinn), the killer of his “favorite second cousin” (Art Carney). But it’s Vivaldi’s top henchman Benedict (Charles Dance), sporting a flashy glass eye gimmick, who learns about Danny’s magical movie ticket and eventually brings other movie characters into Danny’s real world, Ripper among them. Along the way, the tongue-in-cheek humor finds Danny quipping about Schwarzenegger’s catchphrase, “I’ll be back,” and making several references to Amadeus (1984) because he recognizes F. Murray Abraham, who plays a corrupt cop. There’s even a sequence involving Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), where Ian McKellen plays Death emerging from that film. But amid a mobster named Leo the Fart, Quinn’s downright silly performance, and no end of cameos (including digital renderings of Laurence Olivier and Humphrey Bogart), the movie scrambles the viewer’s brain with its nonsensical hodgepodge of metatextuality.

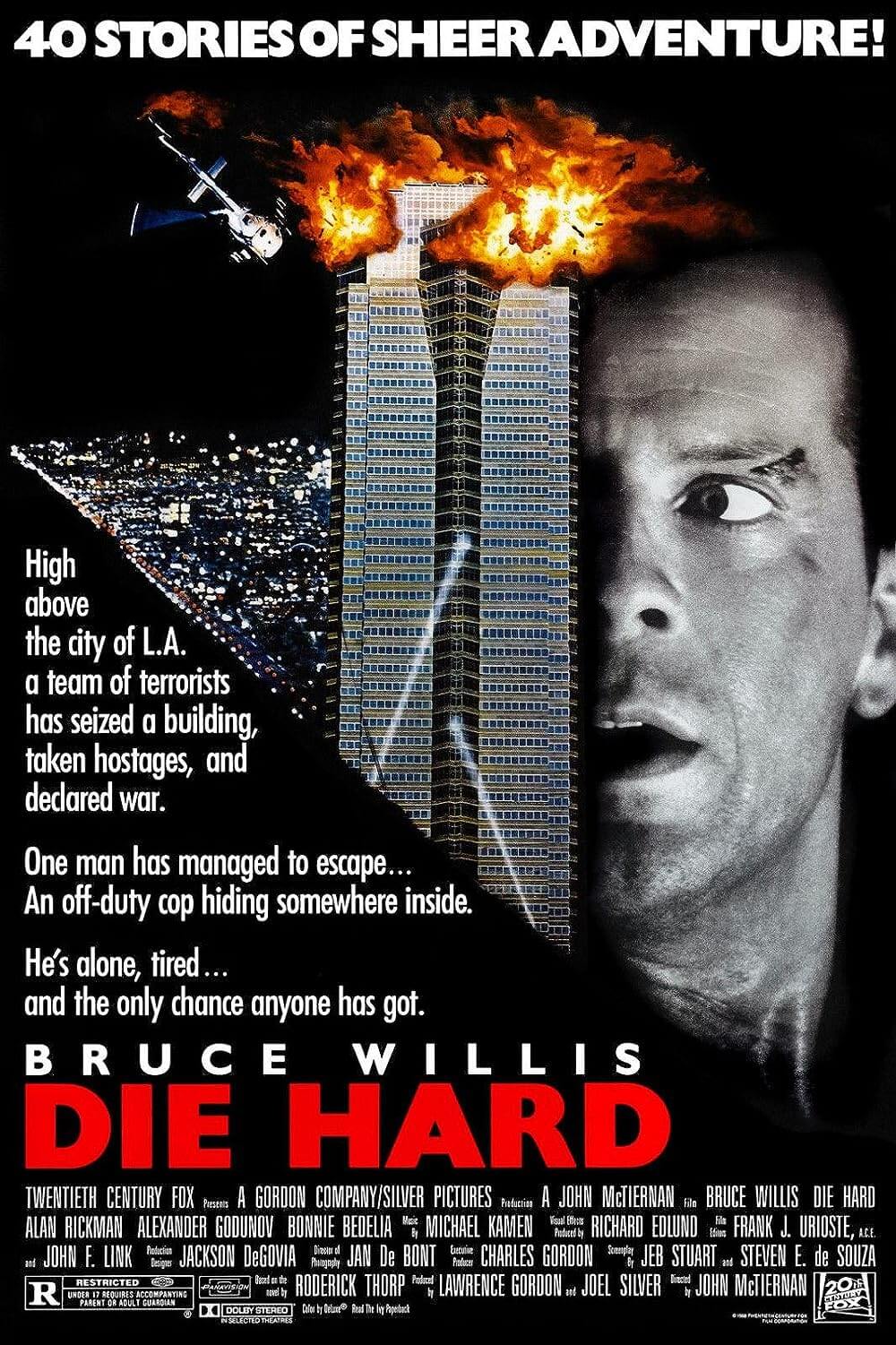

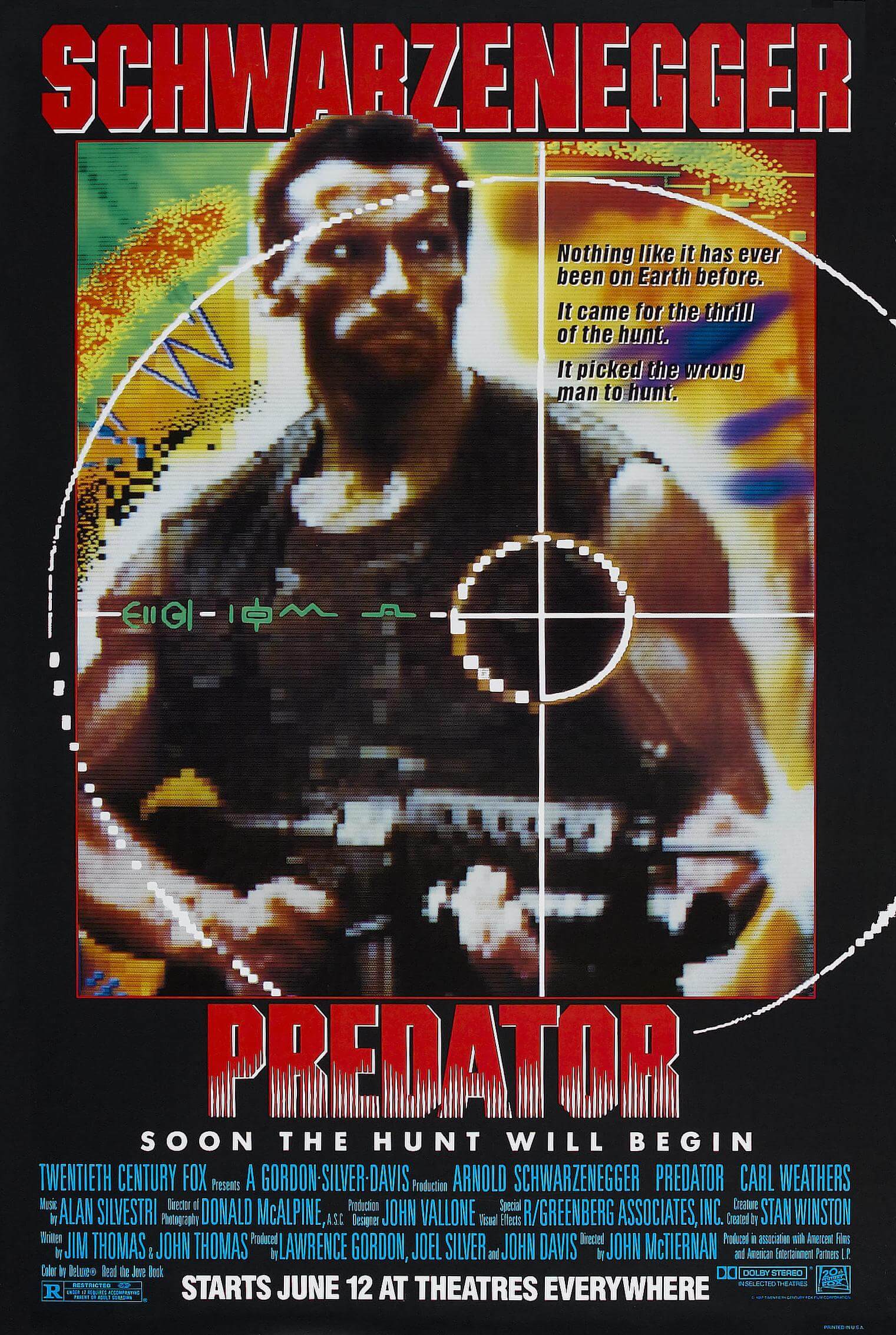

Even so, everyone involved should have made Last Action Hero a winning prospect. Director John McTiernan had helmed some of Hollywood’s best actioners, including Predator (1987), Die Hard (1988), and The Hunt for Red October (1991). The many screenwriters involved have all written better things elsewhere. But the Hollywood machine interceded, leaving the movie without a perspective. Although it’s meant to be a send-up of shoot-em-ups featuring the likes of Schwarzenegger and Stallone, the movie has no argument to make about them, and the manner of its parody seems to be spoofing a brand of action movie that didn’t exist until this film created it. How Last Action Hero ended up like this is arguably a more entertaining and cohesive story than the movie, which has occasional moments of levity and escapism along with just as many scenes that prove bewildering or annoying. The result never comes together into a satisfying whole, and the behind-the-scenes accounts suggest why.

Zak Penn and co-writer Adam Leff laid the groundwork for Last Action Hero just out of Wesleyan University, intending their spec script called Extremely Violent to lampoon Hollywood’s obsession with shoot-em-ups in a style reminiscent of Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985). Their original concept followed a teenager whose dad dies of cancer, so he works through his grief by imagining himself inside an action movie, where he knowingly subverts the world with his knowledge of the genre, helps along a dull good guy who never rises above a tired trope, and learns to become the hero of his own story. When their script hit Hollywood, Columbia Pictures won the ensuing bidding war after Schwarzenegger showed interest in starring. Penn and Leff couldn’t believe their luck; after all, their script’s hero was originally named Arno Slater. But they learned the hard way that getting your script bought in Hollywood doesn’t mean your movie is going to be made. At the height of his popularity, Schwarzenegger negotiated a deal that included a $15 million payday to star and creative powers over the script, which he wanted to be rewritten into a more family-friendly mold.

Although the actor had just finished making the R-rated Terminator 2: Judgment Day, public outcries about violence in the movies convinced the musclebound star to change his image from a remorseless killing machine in several ‘80s action movies to the family entertainment giant of the ‘90s—as seen in Kindergarten Cop (1990), Junior (1994), and Jingle All the Way (1996). In an ironic twist, the studio replaced Penn and Leff with writers Shane Black and David Arnott, the former being the writer of Lethal Weapon (1987) and The Last Boy Scout (1991)—the sort of movies Penn and Leff’s script sought to satirize. Black and Arnott added elements such as the first sequence on the rooftop, Slater as the focus of the story, and the third part of the four-act structure when Slater leaves the movie and spends time in the real world. After arbitration with the WGA, Penn and Leff received “story by” credit, but the revisions weren’t over.

Although the actor had just finished making the R-rated Terminator 2: Judgment Day, public outcries about violence in the movies convinced the musclebound star to change his image from a remorseless killing machine in several ‘80s action movies to the family entertainment giant of the ‘90s—as seen in Kindergarten Cop (1990), Junior (1994), and Jingle All the Way (1996). In an ironic twist, the studio replaced Penn and Leff with writers Shane Black and David Arnott, the former being the writer of Lethal Weapon (1987) and The Last Boy Scout (1991)—the sort of movies Penn and Leff’s script sought to satirize. Black and Arnott added elements such as the first sequence on the rooftop, Slater as the focus of the story, and the third part of the four-act structure when Slater leaves the movie and spends time in the real world. After arbitration with the WGA, Penn and Leff received “story by” credit, but the revisions weren’t over.

Last Action Hero quickly became a production marred by Schwarzenegger’s ideas, the studio’s meddling, and feedback from Columbia’s marketing department about appealing to various demographics. The star convinced Columbia to pay screenwriter William Goldman—whose The Princess Bride (1985) was seen as a model for genre deconstruction—to provide an uncredited rewrite for a cool $1 million. Goldman turned what was originally an evil movie theater projectionist into a nostalgic old fart, built up Danny’s innocence by making him a preadolescent instead of a teen, boosted the secondary villain Benedict (similar to how Count Rugen is much more intimidating than Prince Humperdinck in The Princess Bride), and turned Slater into a more interactive hero instead of a mindless character behaving as he was intended. The director observed, “Goldman gave Arnold a character to play, and he excised 150 toilet jokes.” Carrie Fisher, another of Hollywood’s go-to script doctors from the era, also completed a draft that, according to Columbia, would account for the female perspective; however, watching the film, it’s difficult to imagine of what that might consist.

Meanwhile, everyone and no one was in charge. Columbia chairman Mark Canton was so intent on micromanaging the production that he paid $1 million to the credited producer, Steve Roth, to back away, a tactic he had attempted on the production of The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) during his time at Warner Bros. to disastrous effect. Schwarzenegger took on the role of executive producer, seeing the title as his ticket to oversee every aspect of production. Columbia wrote whatever checks necessary to please their actor, and they pressured McTiernan to hit their June 18, 1993 release date, despite the crammed production schedule. Still, they spared no expense to move the production along, ballooning the budget to $85 million, not to mention countless more dollars spent on marketing. By contrast, Universal’s Jurassic Park, released only a week before Last Action Hero, cost about $63 million and made over $1 billion. Eventually, it was Jurassic Park’s dominance at the box office that took the blame for Last Action Hero’s measly $50 million in domestic grosses.

The critical reception ranged from mildly amused to outright disgust over the production’s blatant commercialism. Writing in Entertainment Weekly, Owen Gleiberman observed that “There’s a deep cynicism at work in making the film-within-a-film such a deliberate piece of junk,” before concluding that the movie “makes such a strenuous show of winking at the audience (and itself) that it seems to be celebrating nothing so much as its own awfulness.” Indeed, Schwarzenegger’s interviews about Last Action Hero seem more interested in the ostentatious promotional campaigns and lucrative product tie-ins than the movie’s substance. He boasts about a multi-million-dollar Burger King deal, a publicity stunt to pay NASA $500,000 for putting the movie’s logo on the side of a space shuttle, and the $200,000 spent on a 40-foot blow-up doll of Schwarzenegger displayed at the Cannes Film Festival. The actor’s interviews from the period and today seem so enthusiastic about the money feeding this big corporate product that he almost forgets to talk about the movie.

The critical reception ranged from mildly amused to outright disgust over the production’s blatant commercialism. Writing in Entertainment Weekly, Owen Gleiberman observed that “There’s a deep cynicism at work in making the film-within-a-film such a deliberate piece of junk,” before concluding that the movie “makes such a strenuous show of winking at the audience (and itself) that it seems to be celebrating nothing so much as its own awfulness.” Indeed, Schwarzenegger’s interviews about Last Action Hero seem more interested in the ostentatious promotional campaigns and lucrative product tie-ins than the movie’s substance. He boasts about a multi-million-dollar Burger King deal, a publicity stunt to pay NASA $500,000 for putting the movie’s logo on the side of a space shuttle, and the $200,000 spent on a 40-foot blow-up doll of Schwarzenegger displayed at the Cannes Film Festival. The actor’s interviews from the period and today seem so enthusiastic about the money feeding this big corporate product that he almost forgets to talk about the movie.

While the star celebrated the film’s lavish expenditures, a few critics, including Roger Ebert, saw glimmers of inspiration amid the chaos. Certainly, Last Action Hero has some fascinating ideas and meta-brand commentary that amuses. Black admitted, “There was a movie in there, struggling to emerge, which would have pleased me. But what they’d made was a jarring, random collection of scenes.” It’s also overlong at 131 minutes, without the structural cohesion or narrative thrust to justify its length. Occasionally, a performer such as Noonan or Ruehl does something memorable. However, when O’Brien’s gobsmacked, obnoxious, know-it-all kid should be pointing out the clichés and leading the story, he’s more often a passenger to Schwarzenegger’s Slater. The star clearly wants to be central, to the degree that he cannot be the butt of the joke without being in on it. At one point, on the red carpet for Jack Slater IV, Slater comes face-to-face with Schwarzenegger and tells him, “You’ve given me nothing but pain.” But that kind of self-harm is inextricable from Last Action Hero, where the movie invites ridicule with bad jokes and disorganized plotting.

Thirty years later, the movie has earned fans who embrace its messiness and apologize for its ungainly qualities. Amid the many celebrity cameos and half-hearted commentary on how movie violence influences teens, Last Action Hero keeps the viewer’s attention for much of its runtime, but around the 100-minute mark, we begin to agree with Slater’s observation: “This hero stuff has its limits.” A product of Hollywood’s insipient, ‘90s-era self-indulgence in productions like Hudson Hawk (1991), Last Action Hero has potential. Imagine a version not unlike Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), with a harmony of theme, character, and aesthetics that push the genre forward by remarking on its formulas instead of jerking itself off. But instead, the movie suffers from an identity crisis, propelled by its Frankensteined screenplay and lack of a single authorial voice. Even company-engineered products from today’s superhero fare seem to have more continuity of vision. Here, the viewer watches random ideas spill out onto the screen, as though Hollywood was vomiting money. It’s sort of fascinating to watch from a safe distance as this bauble shatters from its own weight, but it rarely invests us in what’s happening.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on September 27, 2023. Thanks to Dustin for commissioning a review of the film, which I didn’t love, but it intrigued me to no end. Thank you, Dustin, for your patronage and continued support!)

Bibliography:

De Semlyen, Nick. The Last Action Heroes: The Triumphs, Flops, and Feuds of Hollywood’s Kings of Carnage. Crown, 2023.

Ebert, Roger. “Last Action Hero.” RogerEbert.com, 18 June 1993. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/last-action-hero-1993. Accessed 15 September 2023.

Gleiberman, Owen. “Last Action Hero.” Entertainment Weekly, 9 July 1993. https://ew.com/article/1993/07/09/last-action-hero-2/. Accessed 15 September 2023.

Konda, Kelly. “An Oral History of Last Action Hero: A Crash Course in Hollywood (Part 1).” We Minored in Film, 8 September 2015. https://weminoredinfilm.com/2015/09/08/an-oral-history-of-last-action-hero-a-crash-course-in-hollywood-part-1/. Accessed 16 September 2023.

—. “An Oral History of Last Action Hero: The Ultimate Cautionary Tale (Part 2).” We Minored in Film, 11 September 2015. https://weminoredinfilm.com/2015/09/11/an-oral-history-of-last-action-hero-the-ultimate-cautionary-tale-part-2/. Accessed 16 September 2023.

Taylor, Larry. John McTiernan: The Rise and Fall of an Action Movie Icon. McFarland, 2018.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review