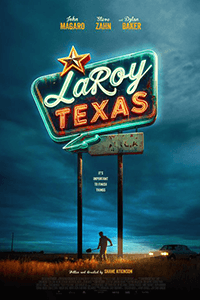

LaRoy, Texas

By Brian Eggert |

Note: LaRay, Texas will play at the 43rd Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival. For the full lineup of films available between April 12-25, check out the schedule here. The film arrives in theaters in limited release on Friday, April 12.

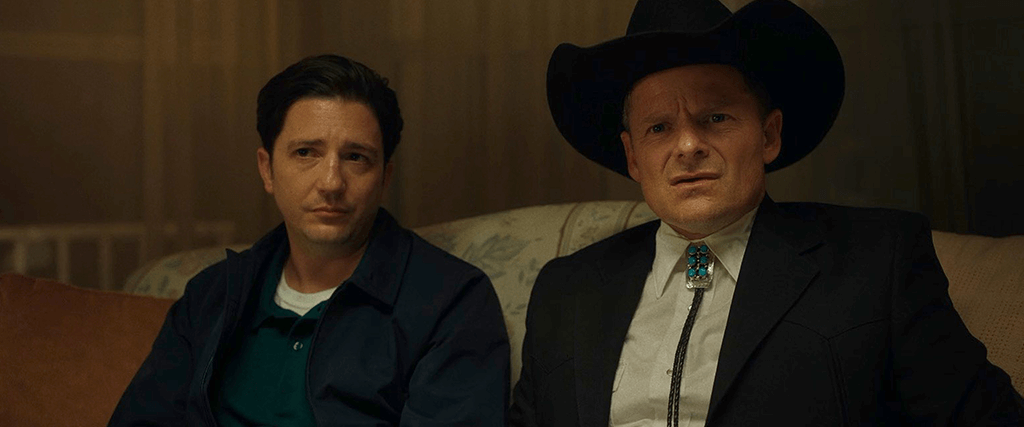

LaRoy, Texas teaches a valuable lesson in its opening scene: Never accept a ride from Dylan Baker. The Happiness (1998) and Trick ‘r Treat (2007) actor specializes in playing seemingly average, unimpressive men with a dark side. Here, he plays Harry, who stops at night to pick up a man whose car has stalled on a Texas backroad. They get to talking, and each of them points out how it’s considered generally unsafe to invite a stranger into your car. But then, so is accepting a ride from someone you don’t know. “Maybe I picked you up so I could kill you,” Harry jokes, suggesting the man’s wife might’ve paid him. The man doesn’t find the suggestion funny and worries there’s some truth to Harry’s claim. Cut to a short time later, when Harry buries his passenger in a field, a moment punctuated by a sharp edit like the punchline of a sick joke. Baker’s character is a hitman in the film, which involves a bag of money, unfaithful spouses, a private detective, and more than one murder. The pulpy scenario doesn’t offer many surprises, but writer-director Shane Atkinson handles it so well that one cannot help but delight in the juicy crime material.

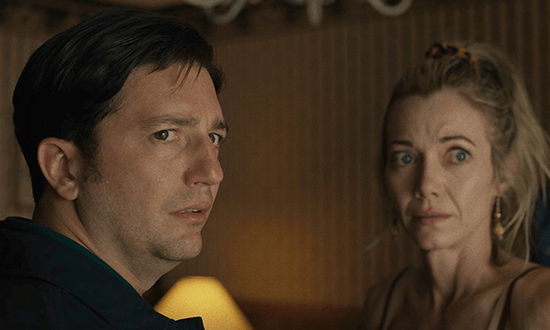

Atkinson makes his feature debut with LaRoy, Texas, borrowing his tone and familiar scenario from other Southern neo-noirs. A clear antecedent is the Coen brothers’ first film, Blood Simple (1984), with perhaps a hint of William Friedkin’s trailer-park noir, Killer Joe (2011). Even though Atkinson isn’t blazing a new trail, he handles his twisting yarn with confident filmmaking, a capable script, and several well-honed performances. Central to them is John Magaro, who also produced the film. Magaro plays Ray, who runs a hardware store alongside his smarmy brother (Matthew Del Negro). Ray agrees to meet with Skip (Steve Zahn), a private eye, though Ray never hired him. Skip, donning a faux cowboy outfit that makes him look like a goofball, snapped a few photos on a recent job and happened to spot Ray’s wife, Stacy-Lynn (Megan Stevenson), having an illicit rendezvous in a seedy motel. Although Skip believes he’s helping Ray by showing him the photos, Ray cannot accept what he sees and tells Skip to mind his own business.

With Skip mocked by local police for being a phony, Zahn brings his usual energy to his private eye role, recalling his dynamic in Out of Sight (1998) as a vaguely criminal but good-natured fellow who wishes he were a big shot. Skip means well, and Zahn conveys that with his generally affable persona. Magaro’s performance is more complex and marked by worn sadness. Stacy-Lynn means everything to Ray, so when he learns she has been cheating, he visits a gun shop. The clerk suggests a shotgun, which Ray tests by aiming the weapon at his temple when no one’s looking. “I think I need something shorter,” he decides. Such macabre, deadpan humor purveys LaRoy, Texas, giving way to its sly manner of getting under the viewer’s skin. But Ray has secrets, too. Take when he trails a mark—used car dealership owner Adam Ledoux (Brad LeLand)—intending to kill him for money, which he needs to fund Stacy-Lynn’s dream of opening a salon. Ray can’t convince himself to pull the trigger, inciting a whole slew of trouble.

Atkinson’s film takes place in a fictional town filled with sordid clubs, scuzzy motels, and neon-glowing bars, shot by cinematographer Mingjue Hu in atmospheric light tinged by orange parking lot illumination and the iridescent glow of unsavory nightspots. These spaces are populated by characters who look shabby, cheap, and desperate. But the film isn’t as miserable as its look suggests. Take a sequence where the dopey Skip and passive Ray confront an unfortunate witness who might know about some missing cash, totalling $250,000. Skip tries a strong-arm tactic and plunges the guy’s head into a toilet. He drowns almost immediately, requiring Ray to revive him. As the interrogation continues, the situation repeats itself to a hilarious effect. All the while, the excellent, twangy score (credited to Delphine Malaussena, Rim Laurens, and Clément Peiffer) consists of acoustic guitars and a persistent but downtrodden melody, lending a light yet weighted personality to most scenes in a manner similar to Carter Burwell’s music on most Coen brothers movies.

Atkinson’s film takes place in a fictional town filled with sordid clubs, scuzzy motels, and neon-glowing bars, shot by cinematographer Mingjue Hu in atmospheric light tinged by orange parking lot illumination and the iridescent glow of unsavory nightspots. These spaces are populated by characters who look shabby, cheap, and desperate. But the film isn’t as miserable as its look suggests. Take a sequence where the dopey Skip and passive Ray confront an unfortunate witness who might know about some missing cash, totalling $250,000. Skip tries a strong-arm tactic and plunges the guy’s head into a toilet. He drowns almost immediately, requiring Ray to revive him. As the interrogation continues, the situation repeats itself to a hilarious effect. All the while, the excellent, twangy score (credited to Delphine Malaussena, Rim Laurens, and Clément Peiffer) consists of acoustic guitars and a persistent but downtrodden melody, lending a light yet weighted personality to most scenes in a manner similar to Carter Burwell’s music on most Coen brothers movies.

The milieu of stolen money, hitmen, and double-crosses, with everyone after the missing cash, adds to the potboiler quality of LaRoy, Texas. Of course, LaRoy is a main character, just small enough to pass as an average American town. But the closer you look, the more you notice it is infested with duplicitous and back-stabbing pests. Still, there’s a tenderness beneath Atkinson’s treatment of his characters. Unlike the Coens, whom critics often accuse of hating their characters, Atkinson allows Ray and Skip some human dignity. Ray is unabashedly devoted to his unfaithful wife, never considering why a former beauty queen would choose someone like him. Later, defeated, he finally musters the strength to ask, “Why’d you marry me?” Her answer is more devastating than one could possibly imagine. However, Ray maintains quiet integrity and meaning in his actions, whereas others seem to flounder aimlessly. As for Harry, he’s the resident Anton Chigurh—a chilling presence determined to carry out his task, no matter the cost, but without the menacing, fateful worldview of that No Country for Old Men (2007) villain.

Somewhat more hopeful and less caustic than the aforementioned Southern neo-noirs, Atkinson’s film gives its characters a sense of value the Coens—steeped in their perspective that the universe is chaotic and meaningless—never would. LaRoy’s citizens aren’t so much the butt of the universe’s joke but rather human beings just trying to scratch their way through life and emerge with some purpose. Darcy Shean, who plays Ledoux’s beleaguered but empathetic wife, conveys a personal philosophy of forgiveness that most other characters in LaRoy, Texas will likely never achieve. Atkinson seems to argue that if these people could just forgive and forget, their criminal goings-on might not get the better of them. It’s not a particularly deep idea, amounting to a superficial version of Blood Simple. But beneath all the stupid choices and cynical worldviews, there’s also, eventually, a tender portrait of the friendship between Skip and Ray, and a belief that marriage might supply an emotional anchor and moral compass. None of these ideas resonate much by the film’s conclusion, but the expert performances and assured filmmaking more than justify this playful genre exercise.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review