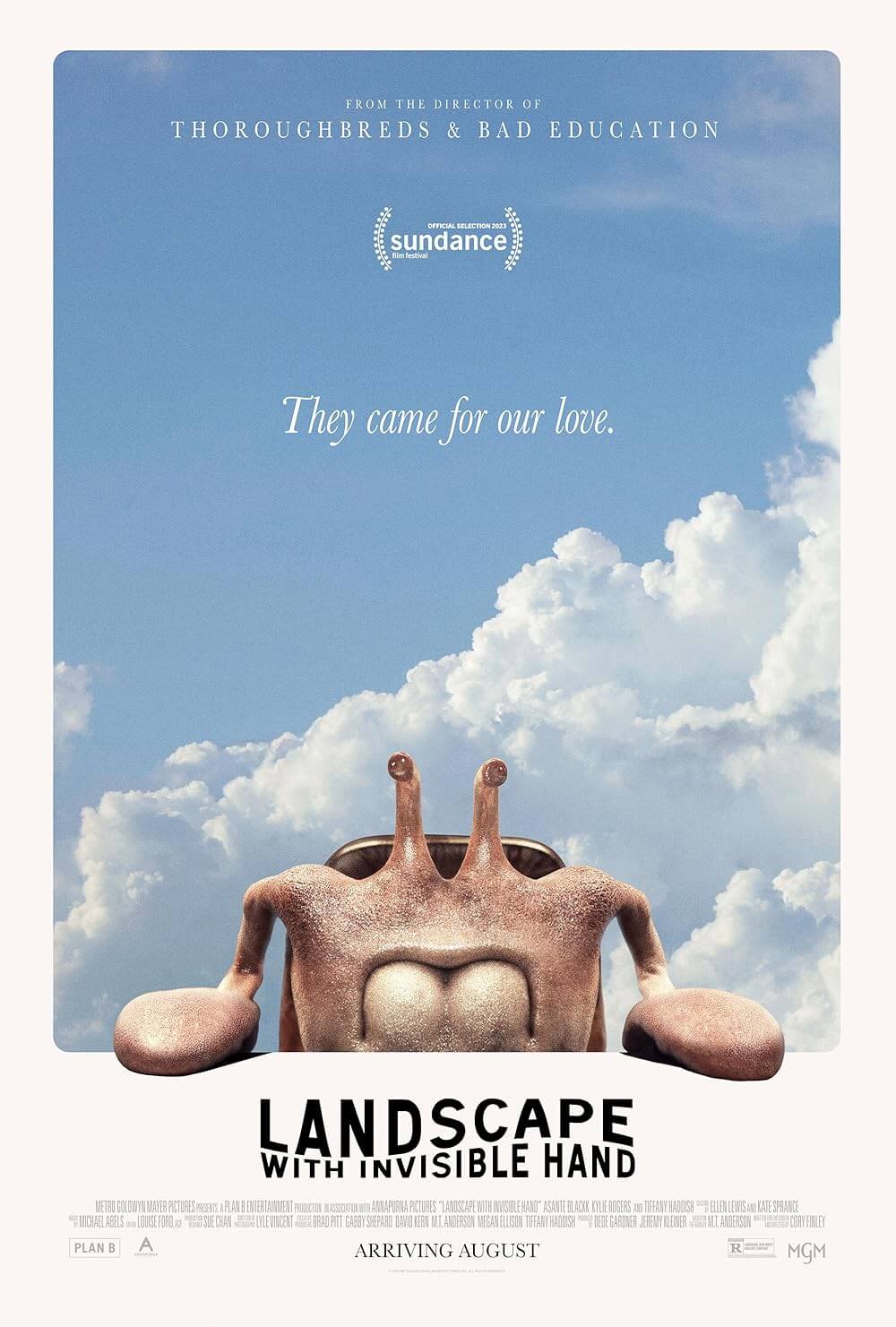

Landscape with Invisible Hand

By Brian Eggert |

How appropriate that Landscape with Invisible Hand should come out now, amid the SAG and WGA strikes, when the greed of Hollywood studios remains central to industry debates. An allegory for how people will sell themselves to corporate overlords to get a big payday, the film is based on a YA book by M.T. Anderson, who specializes in parables about growing up or being trapped within capitalistic systems. Opening in 2036, the story involves an alien species that arrived on Earth many years ago, did away with hostile governments through a nonviolent economic takeover, and made deals with business leaders who saw untold potential in selling out to their new masters, a species called the Vuvv. Those smart enough to embrace and invest in Vuvv technology moved to floating saucer cities in the sky. Everyone else lives in poverty on the surface, narrowly surviving on processed food cubes and menial jobs, if they’re lucky. What’s most compelling about the film is its commentary on maintaining the sincerity of your artistic vision. However, you could also mine the film for its remarks on social media, racial dynamics, class differences, and colonialism.

Adapted by writer-director Cory Finley, the film centers on Adam Campbell (Asante Blackk, a natural screen presence), a high schooler who processes the world through his flat acrylic painting. His father left long ago to pursue opportunities in California but never returned. Now, Adam and his sister Natalie (Brooklynn MacKinzie) live alone with their mother, Beth (Tiffany Haddish, also an executive producer), a skilled lawyer who cannot get work under the Vuvv regime. But when Adam meets a new girl at school, Chloe Marsh (Kylie Rogers), and falls for her, he invites the homeless Marshes to move into their basement. Mr. Marsh (Josh Hamilton, recapturing some of his dad energy from 2018’s Eighth Grade) and Chloe’s disenchanted brother Hunter (Michael Gandolfini) seem gracious enough for the accommodations, though their resentments emerge later. The two families both reap the benefits when Chloe suggests to Adam that their teen romance become fodder for a “Courtship Broadcast,” which finds the couple recording their interactions for their asexual alien audience’s entertainment, earning them a hefty payday in the process.

Adam and Chloe wear nodes on their forehead to distribute their sensory input. The more viewers they attract, the more they get paid. But the ultra-rich Vuvv, who look like fleshly rectangles with floppy tentacles, clearly have no understanding of human relationship dynamics. When Adam and Chloe’s short-lived romance begins to lose steam, one Vuvv feels their broadcast is inauthentic and decides to sue—a lawsuit Adam and Chloe cannot win, and which will place their families in debt for generations. Beth negotiates a solution: she will repay her son’s debt by playing wife to a TV-addicted Vuvv for a couple of weeks. The creature expects Beth to be a compliant stay-at-home spouse, having learned about humans from 1950s-era television shows. Rubbing its tentacle paddles together to speak, it makes sharp orders (“Sit down, wife”) and expects Beth to conform to its ideal mate—complete with an apron and blonde wig it orders for her. The film has a clever way of introducing disturbing twists on otherwise amusing situations, turning its fable-like scenario into a low-key nightmare. The culmination of them comes when the aliens discover Adam’s painting and offer him billions to create more, albeit with some provisos.

Much of what makes Landscape with Invisible Hand so convincing is the world-building, blending realistic emotions in a fantastical situation. The specifics of the Vuvv occupation introduce fascinating ideas. For instance, the aliens pay a neurosurgeon several times his usual salary to be a personal driver because it’s “fashionable” to reduce a powerful human to a menial job. For his part, the doctor wants to support his family, but at what cost to his dignity? In one of the funnier turns, Beth ultimately abandons her new Vuvv husband out of self-respect, prompting the desperate Mr. Marsh to don the wig and apron to reap the financial benefits. Similarly, Hunter hopes to earn his oppressors’ favor by learning their impossible-to-speak language and shaving off his eyebrows, which is the preferred look for humans among the Vuvv. And while these specifics might seem amusing, cute, or even satirical, Finley includes a scene early on where Adam’s fellow students learn that most classes will be replaced by Vuvv broadcasts sent directly to student nodes—prompting an already underpaid English Literature teacher to shoot himself on school grounds in a chilling moment. This is a desperate world, indeed.

Much of what makes Landscape with Invisible Hand so convincing is the world-building, blending realistic emotions in a fantastical situation. The specifics of the Vuvv occupation introduce fascinating ideas. For instance, the aliens pay a neurosurgeon several times his usual salary to be a personal driver because it’s “fashionable” to reduce a powerful human to a menial job. For his part, the doctor wants to support his family, but at what cost to his dignity? In one of the funnier turns, Beth ultimately abandons her new Vuvv husband out of self-respect, prompting the desperate Mr. Marsh to don the wig and apron to reap the financial benefits. Similarly, Hunter hopes to earn his oppressors’ favor by learning their impossible-to-speak language and shaving off his eyebrows, which is the preferred look for humans among the Vuvv. And while these specifics might seem amusing, cute, or even satirical, Finley includes a scene early on where Adam’s fellow students learn that most classes will be replaced by Vuvv broadcasts sent directly to student nodes—prompting an already underpaid English Literature teacher to shoot himself on school grounds in a chilling moment. This is a desperate world, indeed.

Not everything about the Vuvv makes sense. You may wonder why only vintage sitcoms air on TV, or why the Vuvv seem to consume so much mimetic art yet fail to learn anything from it. But a certain degree of suspension of disbelief is required for any allegory, and that’s true of Landscape with Invisible Hand. For his part, Finley’s direction is quiet and restrained, similar to his work on Thoroughbreds (2018). Cinematographer Lyle Vincent shoots the picture in bright, almost soft-filtered imagery that editor Louise Ford structures with a patient tempo. Michael Abels’ delicate indie score employs light notes amid a theremin theme, harkening back to ‘50s-era science fiction, which, similar to this film, often adopted an outspoken lesson in films such as The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) or Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). Elsewhere, special effects supervisor Erik-Jan de Boer, who worked to create the superpig designs for Bong Joon-ho’s terrific Okja (2017), oversaw the Vuvv and flying city designs. Although the CGI can occasionally look cartoony, it’s effective for what Finley sets out to accomplish.

The film debuted at the Sundance Film Festival this year, and MGM picked it up for distribution in late summer, where this sort of R-rated genre mashup of a coming-of-age drama and sci-fi yarn could, and hopefully will, find an audience that appreciates the uniqueness of its vision. The story is refreshingly high-concept, which makes it difficult to advertise, but those who watch it will recognize that it’s something special. Produced by Brad Pitt’s Plan B Entertainment and Megan Ellison’s Annapurna Pictures, two production companies reliable for enlisting creative directors for on-the-margins projects, Landscape with Invisible Hand feels novelistic in a way most major films don’t. That’s a compliment. You get the sense that Finley is exploring the layers and dimensions of Anderson’s book without trying to reduce them to a commercially viable and consumable format. Any creative person will watch this film and relate to its situations. For instance, in Adam and Chloe’s broadcasts, I saw a counterpart for today’s online creators who share almost everything with their followers. But there comes a point where influencers, YouTubers, and creatives sell themselves for a promotional tie-in. Their voice no longer becomes authentic, or they twist their authenticity into a product placement. The Marshes might welcome selling out, but not the Campbells.

That, as it turns out later on, is the point, and it’s what connects the film to the strikes in the entertainment industry. Whether it’s Beth’s refusal to play house with a Vuvv to resolve their family’s financial troubles or Adam’s temptation to compromise his artistic standards, the film asks what your personal integrity and the trueness of your creative output is worth. The writers striking want to protect themselves from being undercut by artificial intelligence that will manufacture a facsimile of creative output, often by pillaging previously published or produced work by human writers. The actors want fair pay for their creative work and residuals from streaming services, and they don’t want their likenesses scanned by computers and used without payment. Late in the film, the Vuvv take a mural that Adam painted about the grim reality of the occupation and add happy smiling faces, changing the mural’s message. The act made me think of some computer program determining whether a screenwriter’s genuine work would be successful according to its algorithm, then suggesting alterations. Where’s the line between supporting authentic creativity and buying into a corporate product? Landscape with Invisible Hand considers these questions with humor and insight.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review