Lady Bird

By Brian Eggert |

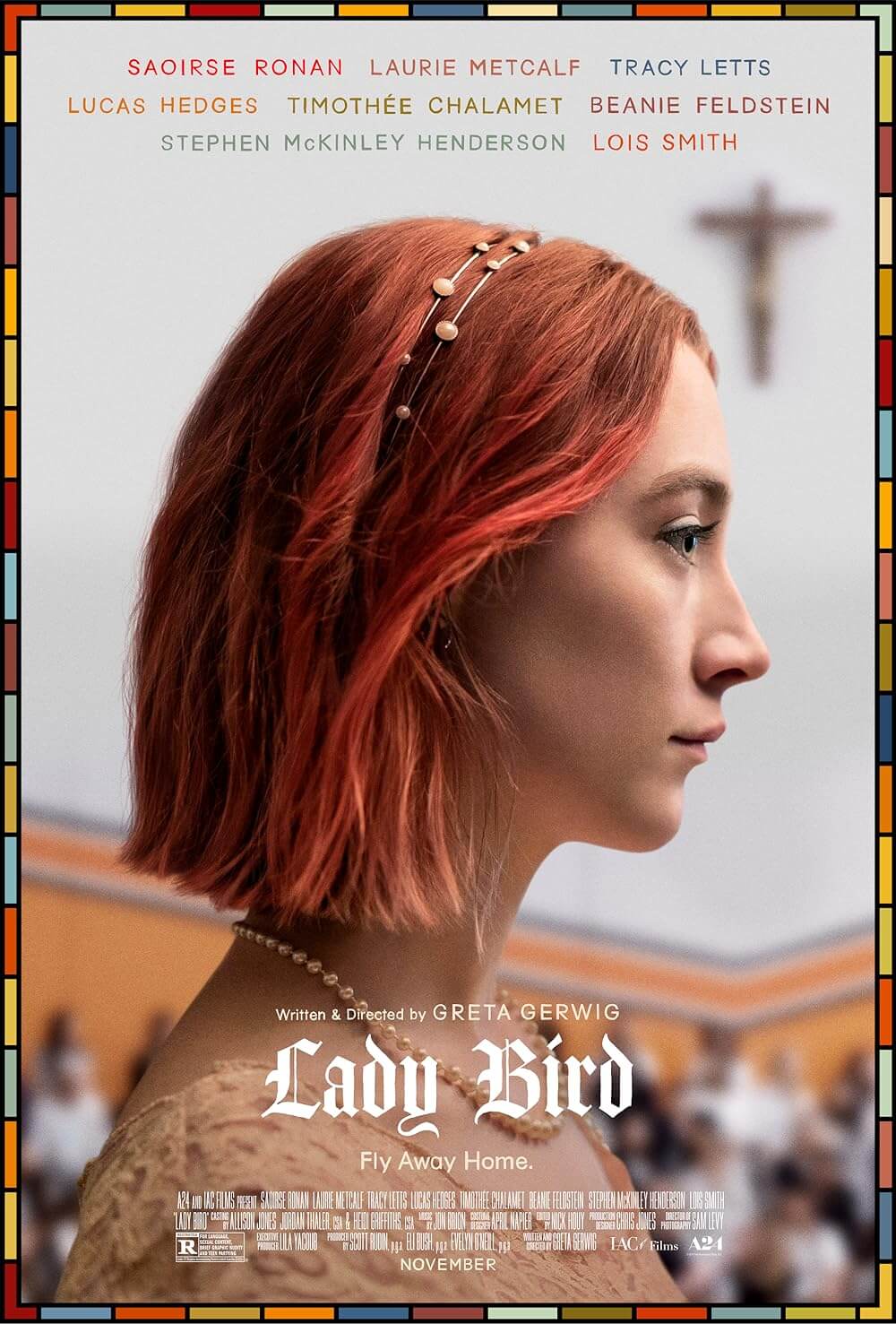

From John Hughes to Kelly Fremon Craig, most coming-of-age films involve a young person emerging from the hell of teendom through a romantic or even sexual rite of passage. Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird remains unique for its emphasis on the central mother-daughter relationship of strained emotions and, later, tender honesty. Saoirse Ronan plays the 17-year-old Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson, an epitome of the self-obsession, relentlessness, and reaching-in-the-dark-for-an-identity of adolescence. Her demanding mother Marion is played by Laurie Metcalf in a passive-aggressive role. An early scene sets the tone of their volatile, polarized relationship. The two finish an audio tape set of The Grapes of Wrath in the car. As they wipe away their tears to Steinbeck’s final lines, an argument builds. Lady Bird grows fed up and announces, “I wish I could live through something!” She then leaps from the moving vehicle. It’s the careless equivalent of getting the last word. She doesn’t even mind the resultant hot pink cast on her forearm, which she wears for much of the film’s remainder. And from this starting point, Gerwig bows a modest, spirited film of idiosyncratic dialogue, mannered style, and sharp insight, providing an incredible showcase for the talents of Ronan and Metcalf, as well as her own.

Gerwig makes her solo writing and directing debut with Lady Bird, having previously shared onscreen director credit with Joe Swanberg for Nights and Weekends (2008). Noah Baumbach, who produced for Swanberg and connected to Gerwig through her presence in the mumblecore movement, would direct the 34-year-old performer in Greenberg (2010), beginning a fruitful collaboration. And alongside Baumbach, Gerwig co-wrote Frances Ha (2012) and Mistress America (2015), two splendid films that showcase her ability to add a natural sense of depth, earnestness, and human dimension to the otherwise thin “manic pixie dream girl” trope. Both films also feel semi-autobiographical. Her character in Frances Ha, for instance, grew up in Sacramento before moving to New York, which is true of Gerwig as well. That’s also the trajectory for the title character of Lady Bird, a film that carries the unmistakable voice of its writer-director on the page and behind the camera, channeling them through Ronan—arguably today’s most vital young actress who has only been better in Brooklyn (2015) or perhaps Byzantium (2013).

Tinged with a red temporary hair rinse and specs of acne, Lady Bird has the kind of relentless personality that insists upon being called “Lady Bird” in all situations. “It’s my given name,” she says. “It’s given to me, by me.” She lives in Sacramento and, in her senior year at a private Catholic high school, she dreams of attending an East Coast university—though she lacks the grades and work ethic to get accepted. Her kind father (Tracy Letts, the playwright-turned-supporting-actor) lost his job and suffers from depression. Her older brother Miguel (Jordan Rodrigues) lives at home with his inscrutable girlfriend Shelly (Marielle Scott). The family doesn’t have a lot of money, which raises tensions, especially for Marion, who works regular double shifts at a psychiatric clinic to keep the lights on. In Marion, Gerwig has found the perfect role for Metcalf, who hasn’t had a film role this substantial since her days of TV’s Roseanne (though, her work on Broadway has earned four Tony Awards). Marion is the sort of incommunicative, inexpressive type this Minnesota native experiences on a regular basis. No wonder Lady Bird calls Sacramento the “Midwest of California.”

Tinged with a red temporary hair rinse and specs of acne, Lady Bird has the kind of relentless personality that insists upon being called “Lady Bird” in all situations. “It’s my given name,” she says. “It’s given to me, by me.” She lives in Sacramento and, in her senior year at a private Catholic high school, she dreams of attending an East Coast university—though she lacks the grades and work ethic to get accepted. Her kind father (Tracy Letts, the playwright-turned-supporting-actor) lost his job and suffers from depression. Her older brother Miguel (Jordan Rodrigues) lives at home with his inscrutable girlfriend Shelly (Marielle Scott). The family doesn’t have a lot of money, which raises tensions, especially for Marion, who works regular double shifts at a psychiatric clinic to keep the lights on. In Marion, Gerwig has found the perfect role for Metcalf, who hasn’t had a film role this substantial since her days of TV’s Roseanne (though, her work on Broadway has earned four Tony Awards). Marion is the sort of incommunicative, inexpressive type this Minnesota native experiences on a regular basis. No wonder Lady Bird calls Sacramento the “Midwest of California.”

Ronan, meanwhile, adopts Gerwig’s mannerisms and speech patterns, creating a performance that might serve as a precursor to Gerwig’s own in Frances Ha and Mistress America. Much like Gerwig’s characters in those films, Lady Bird has a lot of unrealized potential and seems unwilling to acknowledge it. Embarrassed by her family’s modest home, she lies about where she lives or just jokes that she lives “on the wrong side of the tracks.” She says a lot of hurtful things to her mother, but then Marion’s dial with her daughter seems set to disapproving. Lady Bird obsesses over boys, first a fellow drama star from the school play (Lucas Hedges), and then a pretentious bad-boy (Timothée Chalamet) who rolls his own cigarettes and, to sound profound, declares, “I don’t like money, so I’m trying to live by bartering alone.” She also ditches her unpopular-but-genuine best friend Julie (Beanie Feldstein) for the pouty-lipped-but-vacant cool girl (Odeya Rush). Through it all, the Catholic school’s staff (Lois Smith plays an understanding nun, Stephen Henderson plays a wounded priest) allows Lady Bird decided leeway.

The film adheres to a loose structure, reflecting the whirlwind of impulses that compel those high school years. The material breezes by with swift editing and exceptional use of montage courtesy of Nick Houy (who borrows a few tricks from French New Wave directors Godard and Truffaut). There’s also a clear influence from screwball comic timing—undoubtedly learned alongside Baumbach, Gerwig’s partner, and an expert in modern nods to classic Hollywood comedies. Sam Levy lenses the film in grainy and earthy colors, capturing a brand of middle-class normality that feels all-too-relatable. Gerwig also captures the 2002-2003 atmosphere of post-9/11 fragility and uncertainty, along with the omnipresent news broadcasts and phrases like “shock and awe”—even if such things remain other-worldly and distant to a teenage girl in Sacramento.

Gerwig’s script is filled with subtle wordplay and witticisms (Lady Bird says she wants to move to Connecticut or New Hampshire, “where writers live in the woods”), as well as a cruel rebellious streak against a Catholic education. Take when Lady Bird and Julie defend their decision to munch on communion wafers like Doritos because “they’re not consecrated yet.” Or when a pro-life speaker visits the school and Lady Bird offers a scathing, took-it-too-far insult. These behaviors are both funny and awful, desperate in their need for acknowledgment and approval. And while such moments make us laugh, we also worry for the character. Fortunately, the film also shows her internal life, even if what we see represents the most erratic time for a teenager—the time when highs and lows reach their manic peak. Gerwig once referenced Virginia Woolf to an interviewer, noting how the poet observed that men cannot adequately write about what women do alone because they’re not present for the moment. “That’s the world that I feel some ability to report back on,” Gerwig added. While capturing the polarity of personality types between Lady Bird and her mother, she also offers an aching final scene that somehow makes up for their behavior toward one another.

Gerwig’s script is filled with subtle wordplay and witticisms (Lady Bird says she wants to move to Connecticut or New Hampshire, “where writers live in the woods”), as well as a cruel rebellious streak against a Catholic education. Take when Lady Bird and Julie defend their decision to munch on communion wafers like Doritos because “they’re not consecrated yet.” Or when a pro-life speaker visits the school and Lady Bird offers a scathing, took-it-too-far insult. These behaviors are both funny and awful, desperate in their need for acknowledgment and approval. And while such moments make us laugh, we also worry for the character. Fortunately, the film also shows her internal life, even if what we see represents the most erratic time for a teenager—the time when highs and lows reach their manic peak. Gerwig once referenced Virginia Woolf to an interviewer, noting how the poet observed that men cannot adequately write about what women do alone because they’re not present for the moment. “That’s the world that I feel some ability to report back on,” Gerwig added. While capturing the polarity of personality types between Lady Bird and her mother, she also offers an aching final scene that somehow makes up for their behavior toward one another.

Outside of the film itself, Lady Bird arrives in a year fortified with strong female directors making films about women. Patty Jenkins broke box-office records with Wonder Woman, Dee Rees tells a penetrating story of prejudice in the Jim Crow South in Mudbound, Julia Ducournau made an unforgettable cannibal horror film with Raw, and fixtures like Sofia Coppola (The Beguiled) and Kathryn Bigelow (Detroit) populate a list of dozens of female filmmakers with 2017 releases. Call it a coincidence or happy accident, but fighting misogyny and intolerance in North America’s present culture war becomes much easier when the diverse and talented voices of women can be found at the movies. To be sure, Lady Bird comes from a distinct voice, one that has been building and finding itself for years, and with it, Gerwig makes one of the finest debut films on record. Teenage daughters, young women, and mothers everywhere should see it. So should the men in their lives.

Gerwig’s skilled ability to balance humor and pain reveals itself through a constant volley of sweetness and acerbic behavior between Lady Bird and Marion—one of the more complicated and loving mother-daughter relationships on film, alongside Terms of Endearment (1983), Postcards from the Edge (1990), and Brave (2012). When her mother tells her “I want you to be the best version of who you can be,” Lady Bird asks, “What if this is the best version?” The look on Metcalf’s face is painful and forthright, but also rather cruel. By contrast, their Sunday routine involves scoping out houses for sale they could never afford, but nonetheless, represent a rare fantasy they can share. The relationship at the center of Lady Bird proves complicated and intimate, and while the final scenes resolve the biggest fissure between the two, Lady Bird and Marion will never have a perfect mother-daughter friendship. The mutual distance, resentment, expectation, and disappointment will continue. But Gerwig’s observations celebrate Lady Bird’s emergence into the world with a bittersweet celebration, leaving us with a lovable sincerity and fullness of vision that make Lady Bird into a resounding joy.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review