Reader's Choice

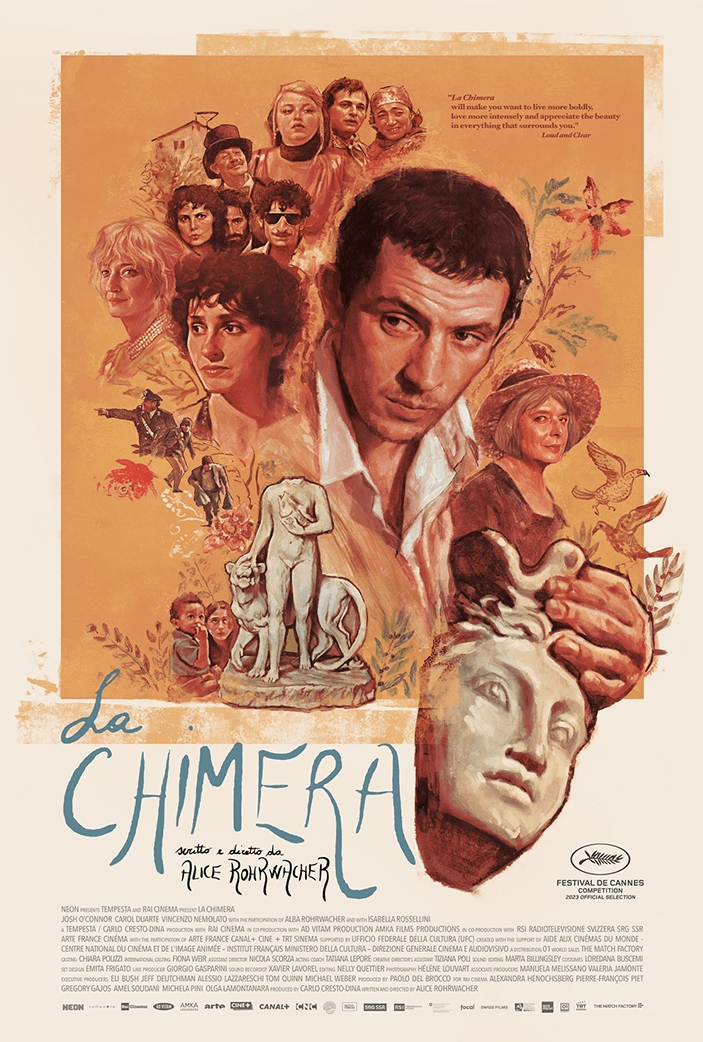

La chimera

By Brian Eggert |

Some art was not made for human eyes. La chimera doesn’t fit into that category, but the film concerns the antiquities in Italy’s vast array of tombs—statues, sculptures, and pottery crafted to pay homage to a god or supply a deceased person with the wares they would need in the afterlife. The origin and intention of this artwork hardly matter to the tombaroli, a band of tomb raiders who seek out Etruscan treasures and sell them to fences, who then sell them to museums and private collectors, with each transaction more profitable than the last. The small community of grave-robbing thieves scrapes by, living a downtrodden lifestyle, where the payday from unearthing a crypt could mean a few months of income. Never mind that Italian law forbids the practice and deems these artifacts state property, and that the country even has a special task force assigned to stop the smugglers and profiteers operating in this lucrative underground black market of historical relics. The characters in La chimera are just trying to scrape by; anything else isn’t their problem. Still, the question remains: Should art be exploited to serve the living, or should we continue to honor the wishes of those who have been dead for more than two thousand years?

Alice Rohrwacher’s film centers on an expert who locates these tombs, drawing from his knowledge and an almost supernatural skill. Josh O’Connor plays Arthur, a bedraggled English archaeologist who has just been released from prison. Unkempt, Arthur appears in a ragged suit, coughs endlessly, and squats in a tin shack on a hill. The writer-director reveals little about his past or how he came to be associated with the tombaroli. Still, allusions to his backstory underscore his hope of reuniting with Beniamina, the elusive love of his life who haunts his dreams and is played by Yile Yara Vianello (the young girl from Rohrwacher’s 2011 debut, Corpo celeste). Even Beniamina’s mother, Flora, played by Isabella Rossellini, yearns for Arthur to be reunited with her. Flora reminded me of Miss Havisham from Great Expectations, a physically weary but imposing force living in a rundown estate. The first person Arthur wants to see after prison (besides Beniamina) is Flora, who defends his quest against her gaggle of daughters, who scheme to put their mother in a nursing home.

Almost immediately upon his release, Arthur rejoins the tombaroli. He begins locating ancient relics, using a Y-shaped stick in the same gestures a water diviner finds the perfect spot for a well. Along with his memories of Beniamina, these sites of the past turn Arthur upside-down, which Rohrwacher and editor Nelly Quettier show in topsy-turvy angles and abrupt flip-flopped images cut into the proceedings. While Arthur seems doomed to repeat the same mistakes that landed him in jail, there’s hope in the form of Flora’s live-in maid, Italia (Carol Duarte), a simple but genuine woman who keeps her two children in Flora’s home a secret. Arthur and Italia have a rapport, exchanging glances; she teaches him Italian, and, much later, they kiss. Might his love for Beniamina subside and be replaced with a newfound affection for Italia? Maybe. But then again, nothing is so conventional in La chimera. Just as Beniamina haunts him, so does his desire to locate antiquities and sell them to Spartaco, a mysterious figure who buys the tombaroli’s inventory.

Offering a less showy but no less accomplished turn as his performance in this year’s Challengers, O’Connor seldom speaks in the film. However, his subtle facial expressions and body language say much about Arthur. He’s an inward figure plagued by memories, dreams, and delusions. Although he rarely questions what his fellow tombaroli do for a living, Italia implants doubt when her superstitious beliefs conflict with the men breaking into burial chambers. If one doesn’t share Italia’s more mystical concern, the men’s treatment of a large sculpture of a goddess—a “new Venus de Milo” as it’s later described—was damaging enough to produce an audible gasp from this critic. Likewise, Arthur’s symbolic act with the sculpture’s head late in the film is maddening if emotionally apt. It’s even worse because the act’s meaning for him doesn’t last or resolve his persistent love of Beniamina—who, we learn, died some time ago. Perhaps no one should own these treasures, not even a museum, and they should remain in the ground. But then, how would anyone learn from them?

Throughout La chimera, Rohrwacher creates formal distinctions between reality and dreams, the past and present, and the living and dead—reminding us that her film isn’t reality, per se, but some manner of cinematic magical realism. When Arthur and the tombaroli face capture by the antiquities police, they scamper off like characters in a silent film or those high-speed sequences from The Benny Hill Show. Another sequence finds Arthur engaging with people on a train in what seems to be a dream. A train attendant gives Arthur a lighter. Did this exchange really happen? The presence of the lighter again later in the film suggests it did. The past has a way of reaching into the film’s present, set in the 1980s: Just as ancient sculptures seem to reappear after the tombaroli uncover them, Arthur’s memories of Beniamina consume his consciousness, and he sometimes has trouble distinguishing between what’s real and what his mind has projected. At a certain point, emotional perception is reality, and there’s no escaping it.

Rohrwacher’s approach also reminded me of Osgood Perkins’ technique on Longlegs, an otherwise unrelated film that deployed a similar device to evoke a mental projection of the past. Both films alternate between a square-shaped frame to show memories, complete with rounded corners and grainy, washed-out colors, with Longlegs using 8mm and La chimera using 16mm film stock, respectively. Cinematographer Hélène Louvart uses softer, grainier stock to suggest Arthur’s memories and dreams of Beniamina, but even the 35mm sequences have rough edges and rounded corners. It’s as though the entire film had been lost in a vault for decades, and we’re watching the feature for the first time since it was rediscovered. But where Perkins’ use of film stock represents the past in an otherwise mannerist film, where the visual style constantly calls attention to itself and distracts from the story, Rohrwacher’s treatment feels more organic. La chimera’s editing is playful and involving, even Godardian at times. To be sure, Rohrwacher’s film has all the trappings of great European arthouse cinema from the 1960s and 1970s.

Rohrwacher’s look at the tombaroli feels just off-center of reality, recalling the vivid fantasy-memory portraits of Federico Fellini’s filmography. The locals in the village where Arthur calls home, if he calls anywhere home, reminded me of Fellini’s treatment of the town in Amarcord (1973). This is familiar territory for Rohrwacher, whose earlier films—Corpo celeste, The Wonders (2014), and Happy as Lazzaro (2018)—each settle on a distinct, localized community. She seems to find their behavior fascinating and indulges their eccentricities with offbeat flourishes, such as when a resident Etruscan expert, Mélodie (Lou Roy-Lecollinet), looks into the camera and tells us that, had the Etruscans not been absorbed by the Romans, Italy wouldn’t be so dominated by machismo today. An elaborate parade sequence pops with vibrant life, characters in drag, and fireworks. The music is just as distinct, ranging from synth to Mozart, from Italian rock to a high-tempo mouth harp in a carnival sequence. The scenes in Flora’s home, or when Arthur and Italia take her to a rundown train station, have a dreamy appeal—yet they speak to the film’s theme about the value of historical spaces. Who owns them, and how should they be appreciated?

There aren’t any good answers to these questions. Offering a wise and eccentric presence, Rossellini’s casting is an extratextual treat that underscores La chimera’s ideas. But her character also gives the best explanation for who owns the past: everyone and no one. To that end, the word chimera can mean a lot of things. To the Greeks, it referred to a creature with the head of a lion, the body of a goat, and the tail of a dragon, which appears in many mythological stories. Rohrwacher uses the term’s more general meaning of a futile and impossible dream. Arthur’s yearning to locate the loving specter of his past echoes that of black market art dealers and collectors, hoping to grab onto some aspect of the region’s history by possessing it. But it’s a vainglorious ambition, arguably best left to preservationists, not profiteers. Take one sequence where Arthur and his pals break the seal on a tomb. Before they do, Rohrwacher shows the undisturbed chamber; the murals on the stone walls feature bright colors that dilute upon some combination of hydrolysis and oxidation. Such careless contamination of these sites disturbs intended resting places and fails to preserve the location as true archeologists might. Arthur learns this lesson too late in La chimera, chasing an impossible dream, trapped in the dark, guided by a single source of light, only to find an answer in the form of a fantasy.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on July 25, 2024.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review