Reader's Choice

Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter

By Brian Eggert |

Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter opens with scrambled video from an overused cassette. Those familiar with Joel and Ethan Coen’s Fargo (1996) will recognize the image as the opening titles from that film. “This is a true story,” the titles falsely claim, along with details about when the event took place and how the names have been changed. Otherwise, the story has been told “exactly as it occurred.” This disclaimer has haunted moviegoers and true crime fanatics for decades, prompting countless investigations and speculation about the film’s actual events, even though Ethan Coen clarified at the time, “You don’t have to have a true story to make a true story movie.” Noah Hawley, showrunner of the FX’s anthology series Fargo, has maintained that tradition, and with each season, viewers question whether or not real events inspired the show. Truth becomes speculative fiction in the 2014 breakthrough film by David and Nathan Zellner, a film that, besides being wrapped up in Fargo’s post-release intertextuality, actually tells a real story. Well, sort of. Besides its questions of truth and allusionism, Kumiko is a beautiful if tragic tale that remarks on depression and media obsession with a touch of magical realism underscoring its profound sadness.

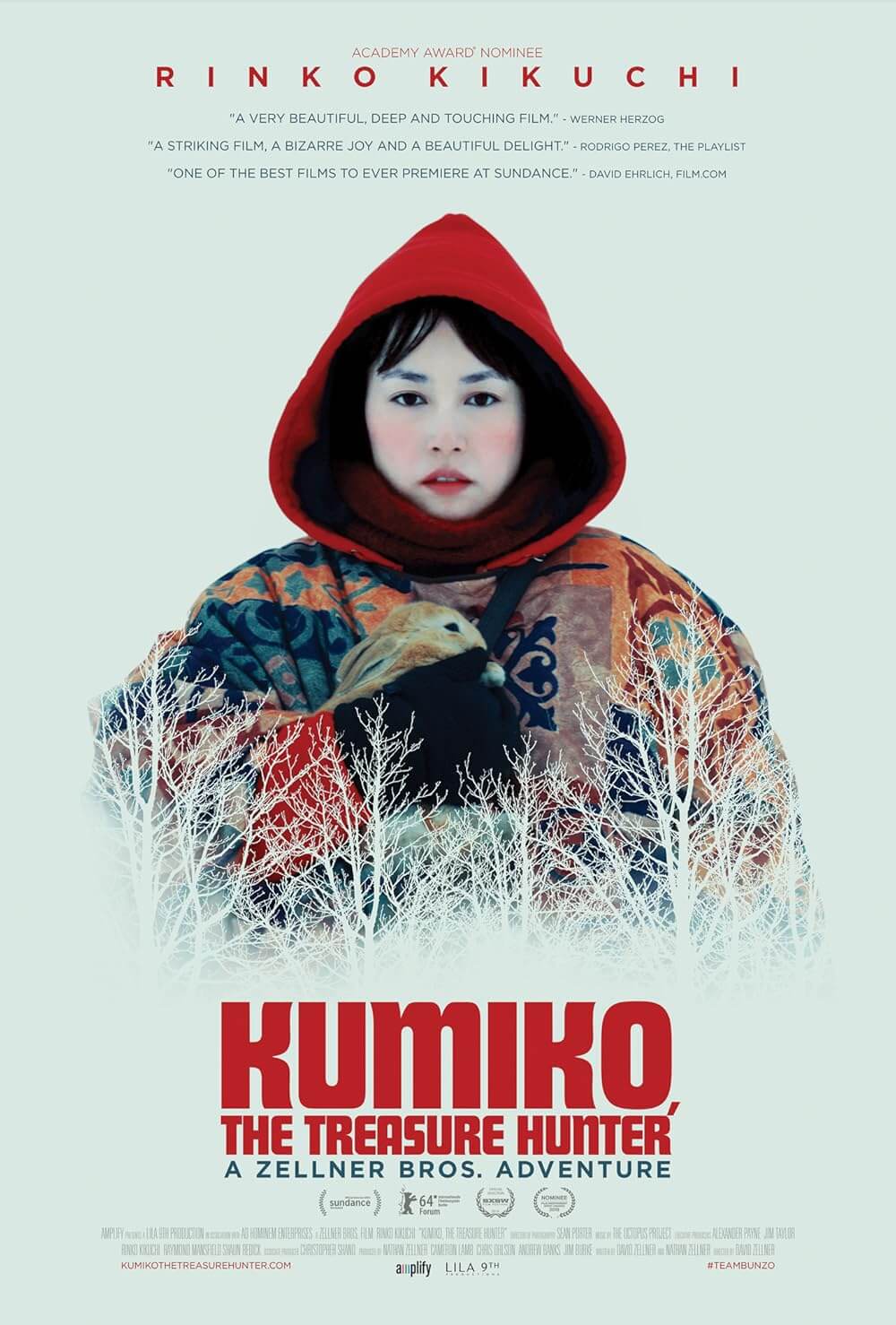

Played by Rinko Kikuchi, Kumiko is a Japanese woman living in Tokyo. At 29 years old, she is the senior “Office Lady” at her nondescript job, where she assists a bored executive who thinks she’s too old for her role. Although many women her age have married by now, Kumiko remains single, which she’s reminded of during nagging calls from her mother. She sees an old friend, now married with a young child, and glimpses what her life might have been. Kumiko has nothing but a small apartment and a pet rabbit, adorably named Bunzo. Others may think Kumiko hasn’t lived up to her potential, but she has a “destiny,” or at least, she has invented one to fill her life. In the first scene, a treasure hunt leads Kumiko into a cave near a beach, where, under a rock, she finds a VHS tape of Fargo. She watches the cassette endlessly, fixating on the scene where Steve Buscemi’s criminal character, Carl Showalter, hides a case of ransom money in the snow. Kumiko measures the lengths in the fence, looks at maps of Minnesota, and creates a needlepoint treasure map, all the while imagining herself as a Spanish conquistador looking for a modern-day El Dorado.

Much of what occurs in Kumiko never happened. The Zellners based their film on an urban legend that spread quickly on the internet in 2001 after Takako Konishi, a Tokyo native, was found dead between Brainerd and Fargo, in Detroit Lakes, Minnesota. Sometime earlier, Officer Jesse Hellman of Bismark, North Dakota, encountered the lost Konishi, who appeared out of place in a black mini-skirt during a northern winter. Hellman tried to help her, conducting a conversation via pocket translator. She mentioned the word “Fargo” and seemed to be carrying a hand-drawn map, and Hellman’s colleague assumed she must be looking for that cash from the Coens’ film. Many reporters had come to the area, searching for information about the crime scenes from Fargo. Where did the highway murder occur? Did the killer really dispose of bodies in a woodchipper? They were disappointed to learn no such events happened outside of the film. Everyone thought that Konishi must be another one of those people who thinks Fargo is real. Eventually, Hellman put her on a Greyhound toward her destination. Similar speculation led by internet and media outlets guessed that Konishi had come looking for the $1 million in cash buried by Showalter and died from exposure.

Like the media, the Austin-based Zellners heard about what happened and decided, “There were so many gaps in the story that made us feel like we needed to fill them in ourselves, just to satiate our own curiosity.” In the meantime, Paul Berczeller made a short documentary in 2003, This Is a True Story, detailing what really happened to Konishi, or at least the facts of the case: While in Tokyo, Konishi had a love affair with an American businessman from Minnesota. She came looking for him, only to discover he had relocated to Singapore. After her encounter with the Bismark police, she checked into the Quality Inn in Fargo, where she made a 40-minute call to Singapore the night before her death, presumably to her former lover. Although no alcohol was found in her system, Konishi reportedly emptied two bottles of champagne, took a blend of downers and antipsychotics, and went out into the cold, where she died. A suicide letter to her parents received in the mail three weeks after her death confirmed her intent to end her life.

Playing with the distinction and intermingling of reality and fiction in the same manner as the Coens do in Fargo, the Zellners rethink Konishi’s story. They shed the facts and their subject’s woeful end for a no less melancholy, oddly uplifting folktale—the sort of traditional word-of-mouth story that has some long-forgotten basis in fact, but it’s been changed over time like the message in a game of telephone. The film is not so much about elucidating facts as searching for some ecstatic truth, in the same way that art gets to the truth through expression. Konishi’s story has that effect on people, for some curious reason. Although there are countless unexplained deaths every year—every day, even—the mystery behind Konishi’s death inspired not only online speculation and the Zellners’ film, but also Berczeller’s short doc and a nonfiction book by Jana Larson, Reel Bay: A Cinematic Essay, which details how the author has fixated on the circumstances of Konishi’s death. The phenomenon that sprung up around the incident is indicative of society’s rampant need for answers, even if it means producing them when none materialize as the Zellners did.

In this film, Kikuchi, who also receives producer credit, plays Konishi by carefully walking the line between someone who’s delusional and someone who’s a desperately lonely person searching for something to fill up her empty life. At first, she might seem rather obsessive, wearing out her copy of Fargo until she must replace the VHS copy and player with a DVD setup. At the same time, the reminders that she has not lived up to her potential mount, and her small rebellions—spitting in her boss’ coffee, abandoning a friend’s child at a restaurant—lead to a more serious choice. She prepares by leaving Bunzo on a subway, a move that surely tests the viewer’s sympathy for her. Then, she takes her boss’ corporate card and flies away to “The New World” of wintry Minneapolis, where she does not speak the language. There, she hitchhikes, stays in a crummy motel, and tries to make her way to Fargo. She has no possessions for the trip, aside from her homemade treasure map and a stark red hoodie, which she covers with a motel bedspread cut into a makeshift winter coat. A kindly but dopey cop (David Zeller) finds Kumiko and attempts to help her, taking her to a Chinese restaurant in the misguided hope of a translation. She sees his help as a bid for romance, but he’s married and has kids, and she reels from his rejection and assertion that Fargo isn’t real, and her journey is for nothing.

The last scenes find Kumiko wandering the oppressive emptiness of flat, Midwestern farmland covered in blinding snow. Her bright garb in this landscape has the effect of George Lucas’ THX 1138 (1971), where characters stand out in a white void. The closest comparison to the ending might be the overwhelming and fantastical revelation at the end of Lars von Trier’s otherwise punishing Breaking the Waves (1996). But instead of heavenly bells ringing for the film’s golden-hearted protagonist, the Zellners imagine a whimsical finale in which Kumiko arrives at the fence from Fargo, uncovers the cash, and walks off into the horizon, having fulfilled her destiny. Joy appears on Kumiko’s face for the first time, revealing how much control and restraint has gone into Kikuchi’s performance. A particularly heartrending detail arrives in the form of Bunzo, who appears out of nowhere at the fence, and whom Kumiko takes into her arms for her fateful walk. Of course, what’s so saddening about this otherwise hopeful conclusion is the grim reality to which it presents an alternative. Even as the ending brings a warm smile, it masks a pang for Konishi, whose loneliness and depression found her isolated in a strange land with a feeling of hopelessness.

The Zellners apply a restrained aesthetic to Kumiko, realized with cinematographer Sean Porter’s clear and symmetrical compositions, arranged with editing that builds the narrative patiently. The sharp images present Tokyo in grayish, lifeless spaces to reflect its main character, but when Kumiko is set to begin her journey, the Zellners include an uncanny shot of workers de-icing a plane at the airport—an almost mythic-looking preparation ritual. The filmmakers intentionally rob Tokyo of the color and vibrancy often associated with the city in cinema, equating Kumiko’s home with the shabby, barren wasteland that is rural Minnesota in winter. In such dour surroundings, Kumiko, who barely speaks, might be a cipher if not for Kikuchi’s ability to convey much through her inward character. The sound design and score by frequent Zellner collaborators, The Octopus Project, adds an aural layer to Kumiko’s inner journey. The music in the climactic scenes evokes the psychedelic journey to “Beyond” from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), when Kumiko wanders the frozen wilderness, cold and sickly, and, for the briefest moment, sees the suitcase frozen in the ice. By contrast, the victorious song that plays during the end credits suggests Kumiko’s state of bliss, perhaps achieved in the last, delusion-driven moments of her life.

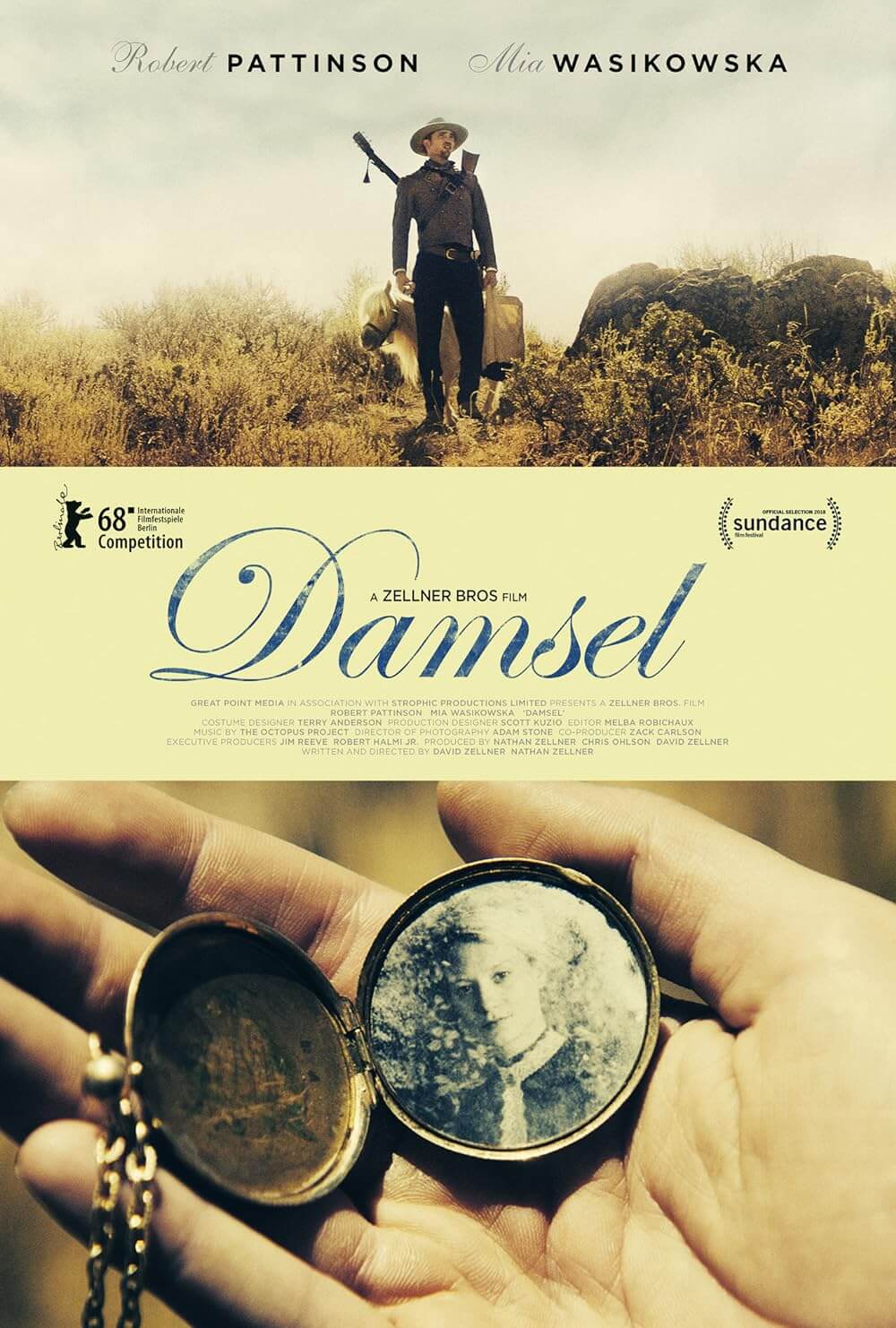

Kumiko premiered at Sundance and became a festival darling, earning several awards on the circuit. Writing for Film.com, David Ehrlich declared it “one of the best films to ever premiere at Sundance.” This did not amount to box-office receipts, however. The distributor Amplify couldn’t crack the metatextual aspect of the story enough to sell it. How do you advertise this high-concept scenario, somewhat dependent on the viewer’s knowledge of the real-life case and the Coens’ film, to general audiences? As a result, the Zellners didn’t pop the way they should have, nor did they become household names like the Coens. The commercial whimper with which Kumiko arrived was followed by another underseen, underappreciated, but no less quirky and uniformly excellent offering, with Damsel (2018). A decade after Kumiko’s release, however, Bleecker Street acquired the distribution rights to re-promote the cult oddity in advance of the Zellners’ latest, Sasquatch Sunset (2024).

Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter is a fascinating case of media, culture, and reality intertwining, becoming inseparable from one another. The Zellners contribute to an ongoing conversation about cinema and its representation of true stories, joining the Coens and anticipating Hawley in their assertion that film—or, in Hawley’s case, television—is an expressive medium first. Whenever a film tackles a historical subject based on actual events, some critic or commentator will inevitably balk at its inaccuracies, missing the point that cinema is not a medium of historical record but artistic representation. Poetic license is not only warranted but inherent, inevitable, and inextricable. The film embraces this notion with a self-reflective and intertextual appreciation of the real story and Fargo, yet with a “print the legend” perspective toward American storytelling, which prefers a good yarn over uncomfortable facts. Its mythological account of Kumiko, and by extension Konishi, delights as much as it haunts.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on April 9, 2024.)

Bibliography:

Berczeller, Paul. “Death in the Snow.” TheGuardian.com, 5 June 2003. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2003/jun/06/artsfeatures1. Accessed 30 March 2024.

Ehrlich, David. “Sundance Review: ‘Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter,’” Film.com, 27 January 2014. http://www.film.com/movies/sundance-review-kumiko-the-treasure-hunter. Accessed 30 March 2024.

Vu, Maria. “How the Fake Treasure In ‘Fargo’ Sparked A Modern Day Myth.” Metaflix.com, 15 November 2020. https://www.metaflix.com/discussion/2020/11/15/how-the-fake-treasure-in-fargo-sparked-a-modern-day-myth/. Accessed 30 March 2024.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review