Kubo and the Two Strings

By Brian Eggert |

For their fourth picture, Laika, the Oregon-based stop-motion animation studio behind Coraline (2009), ParaNorman (2012) and The Boxtrolls (2014), once again places a young hero at the center of an adventure marked by dark, occasionally heavy themes, and resounding tenderness. Kubo and the Two Strings encapsulates what we have come to learn is the archetypal Laika story structure: a young child with a unique perspective, one that could even be considered a curse or infirmity, sets out on a quest for answers, revealing a world of fantasy and a severe dose of emotional reality in the process. This is not to suggest Laika’s formula has grown tiresome; quite the opposite, since by comparison the output by so many other animation companies today seems loud, lazily designed, and less dedicated to their story and artistry. Kubo and the Two Strings is no different from any Laika film, in that it remains of a superior class.

Following a story by Shannon Tindle and Mark Haimes, the screenwriters (Haimes and Chris Butler) borrow much from Asian storytelling traditions, specifically Japanese culture. As so, Kubo and the Two Strings may not immediately resonate with Western audiences, but the narrative remains universal to anyone versed in classical adventures from Homer’s The Odyssey to Conan the Barbarian. Also, more than once during the film, director Travis Knight channels Akira Kurosawa’s samurai pictures such as Seven Samurai (1954) or The Hidden Fortress (1958)—the latter being the origin of Star Wars (1977), another definite comparison. Indeed, the story itself feels worthy of a great Japanese master, but with the requisite magic and wonder of a storybook-come-to-life. In it, Kubo, a one-eyed Japanese boy, leads a tale of great bravery, ghostly immortals, humans transformed into animals, and a personal quest for family and identity.

Moreover, Kubo and the Two Strings contains an overarching theme—occasionally heavy-handed—about storytelling itself. The film might be called a story-within-a-story, and it’s ever aware of its status as such. “If you must blink, do it now,” says our narrator, Kubo (voice of Art Parkinson), who tells us his tale and warns that we must pay attention to every detail and not look away. As a result, the film establishes a series of expectations for the viewer from the outset and, in Laika’s exceptional fashion, lives up to them in terms of thematic heft. And while the ending feels somewhat underwhelming, Kubo, a storyteller in his village, also bemoans that “people like an ending”. Along with the filmmakers, Kubo undoubtedly believes the journey’s the thing; conversely, the destination is where the adventure stops.

Let’s take a few steps back. The story begins in a cave outside a quaint village. There, Kubo’s mother has raised him alone, hiding him from her two dreaded, Noh-masked sisters and their master, Kubo’s grandfather, the Moon King, who has taken Kubo’s left eye. The Moon King now wants the right eye, because without it Kubo can live as an immortal with his family in the heavens, but that also means he will be blind to the beauty of humanity. Even being one-eyed and mortal, Kubo has received some magical powers from his parents—an enchanted mother and a legendary (but now dead) samurai father, named Hanzo. For now, Kubo uses his magic to tell elaborate stories, often without an ending, in the village. He accompanies each performance with music from his shamisen, a traditional Japanese lute with a square body. When Kubo plucks the strings with his bachi, he commands pieces of paper to fold into elaborate origami figures and act out any story of his choosing.

Kubo’s talents don’t stop there, and his powers grow through the course of his adventure. When his eerie spectral aunts (both voiced by Rooney Mara) attack the village one night, it sets Kubo on a quest to acquire three artifacts his father left behind to defeat the Moon King: the Sword Unbreakable, Armor Impenetrable, and Helmet Invulnerable. Along the way, two guides, known simply as Monkey (Charlize Theron) and Beetle (Matthew McConaughey), the former an über-protective monkey, the latter a forgetful and heroic beetle-guy, join Kubo. To obtain Hanzo’s armor, they face a series of massive, luminescent monsters, from an incredibly designed towering skeleton to an undersea creature composed almost exclusively of giant, hypnotic eyeballs. When Kubo finally squares off against the Moon King (Ralph Fiennes, bringing tragedy to his villain), it begins as a fight between a boy and a glowing dragon, but then gives way to something more profound and spiritual.

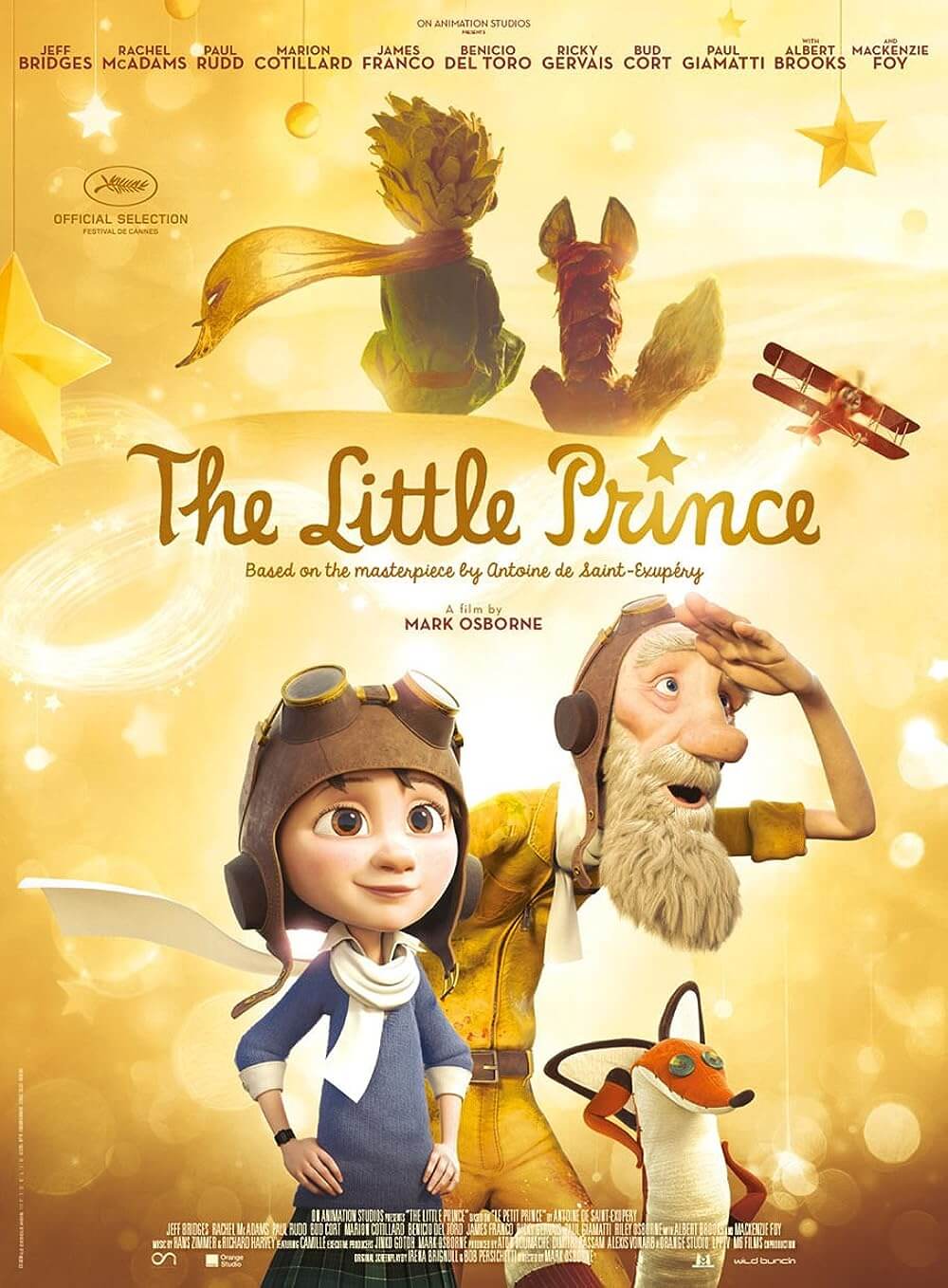

From start to finish, several moments in Kubo and the Two Strings force us to pause and appreciate the beauty of Laika’s animation. And yet, there need not be two screenings—the first to get through the story, the second to digest the on-screen splendor—because the studio understands that their visuals serve the story, not the other way around. With a combination of computers, 3D-printed figures, robotics, and manual frame-by-frame movements, the animators engage in a painstaking process that feels reminiscent of other animated features (most recently, The Little Prince), yet contains an aesthetic quality that is unique within animation. (Fans of the final, rather existential, behind-the-scenes sequence from The Boxtrolls will want to wait for the mid-credits scene here, where we see the imposing scope and scale of one puppet.) What’s more, Laika’s films may be the only pictures in any medium to justify the expense of 3D, as the effect renders the animation like a living relief sculpture.

While the film prepares its audience for an unsatisfying ending, upon reflection, that preparedness is rewarded by a conclusion that satisfies our emotional needs, but perhaps not our need for spectacle. It’s difficult to outperform the film’s earlier monsters, so memorable and haunting; whereas the Moon King seems diminutive by comparison. These are minor quibbles, however. Kubo and the Two Strings has nevertheless been uniquely structured to draw us in for another viewing, as it echoes on emotional levels that may be felt with more impact on screening two or three. This is the case with all Laika pictures; you want to watch them again and again. And though I may rank Kubo and the Two Strings as my least favorite Laika release, it remains better than most animated features available to audiences. If Laika hasn’t already earned a place among the best animated studios working today, the studio’s consistent body of work so far has surely earned them that status.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review