Kraven the Hunter

By Brian Eggert |

Kraven the Hunter continues Sony’s project of giving Spider-Man villains solo movies, turning them into heroes who have little possibility of ever encountering the web-slinger. “Villains aren’t born. They’re made.” That’s the tagline on the poster, but it’s difficult to imagine the Kraven of this movie becoming the bad guy from the comic books. In a curious choice that aligns with the abysmal Venom movies, Morbius (2022), and Madame Web (2024), Sony has manufactured yet another tentpole out of a Marvel intellectual property without showing much interest in character integrity. By turning Kraven into an avenger of justice and a punisher of untouchable criminals, he resembles the villain only in appearance, and even then, only slightly so. With these spinoffs, it’s worth asking: Who is Sony trying to please? Die-hard fans will surely balk. The casual superhero movie viewer may not get it. And everyone else won’t care. In trying to please everyone with an accessible villain origin story in Kraven the Hunter, Sony risks pleasing no one.

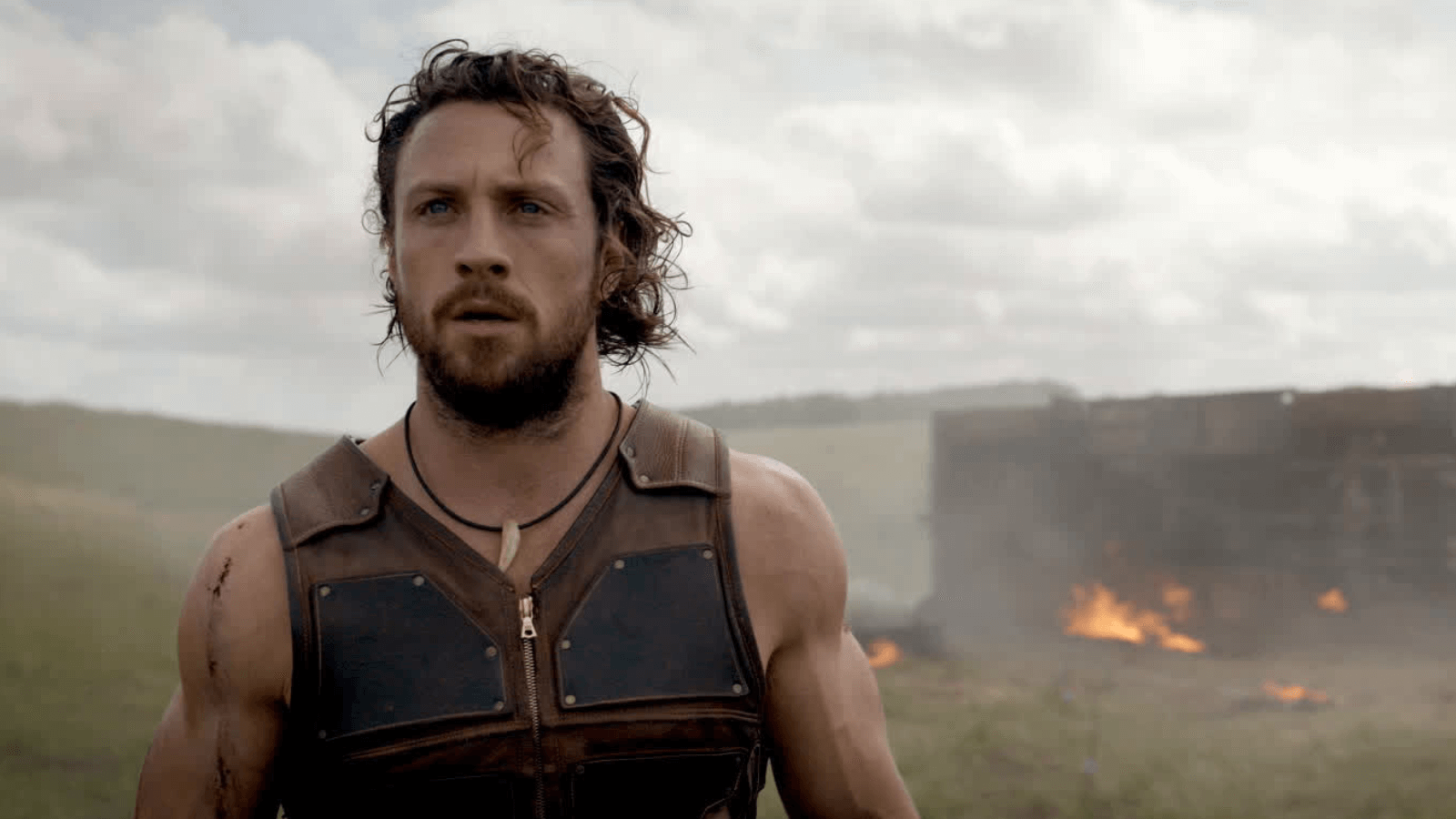

Aaron Taylor-Johnson plays the titular character, Sergei Kravinoff, who becomes an anti-hero on par with The Punisher. After acquiring mystical powers from a blend of lion’s blood and Voudou magic, he can psychically communicate with animals, see like an eagle, climb like a monkey, and kill like an apex predator. His parkour skills make Jason Bourne look slow and untalented, while his abs put Bourne’s to shame. Kraven must have tough skin, too, given how much he runs barefoot on concrete or slides down trees without gloves. He adopts the name Kraven, explaining with self-satisfaction that it’s spelled with a “K.” But he’s also known as The Hunter, with the reputation of a mysterious vigilante in the criminal underground. Yet, his secret identity is a poorly guarded secret. Kraven seems to not know that security cameras are a thing, and, in an elevator, someone asks him what he does for a living. “I hunt… people,” he says, in a scene that makes no logical sense but looks good in a trailer.

The convoluted story involves macho, macho men puffing up their chests, both within the Kravinoff family and amid warring crime factions. Nikolai (Russell Crowe), Kraven’s Alpha Male father, is a feared crime boss and big-game hunter. Aleksei (Alessandro Nivola), who transforms into the villain Rhino if he doesn’t receive a constant chemical antidote, maneuvers against Nikolai. Also in the mix is The Foreigner (Christopher Abbott), a hitman who can hypnotize his targets. Kraven gets pulled into the conflict between his father and Aleksei for reasons that are not worth exploring. He seeks the help of an attorney, Calypso (Ariana DeBose), who dabbles in Voudou and archery. But after the kidnapping of his half brother, Dmitri (Fred Hechinger), a coward with chameleonlike abilities (Any guesses on which villain he will become?), Kraven sets out to stop everyone.

Anyway, that’s the best plot summary I can muster. Things happen in the movie not because the characters drive the action but because the writers do. Richard Wenk, Art Marcum, and Matt Holloway receive credit for the screenplay, though it has probably been punched up by a dozen others, leaving the overall story in disarray. Rife with expositional dialogue, Kraven the Hunter features lines such as “The hunter becomes the hunted” and other banalities. The movie is all plot and no texture, populated by an excellent cast with few opportunities to display their talent. For instance, the painful attempts at one-liners and comic relief between Kraven and Calypso underscore the subpar writing and the actors’ lack of screen chemistry. Taylor-Johnson, an actor seldom cast in material that showcases his skill, has nothing compelling to do here. What does Kraven want? He hunts bad people and brings them to bloody ends, all because of his daddy issues. But what are his personality traits beyond his resentment toward Nikolai, physicality, and superhuman abilities? He is another in a long line of comic book movie characters who are little more than empty IP vessels.

Watching Kraven the Hunter, I felt like one of those people who looks for every gaffe and adds them to the goofs section on IMDb. Some awkward looping here, some continuity errors there. At one point, during a conversation between Kraven and Calypso in the former’s Siberian lair, DeBose’s face appears to be a digital mask over her existing face. I suspect some late dialogue changes were needed, and this solution was more cost-effective than reshoots. Instead of reconstructing a set and reshooting the entire scene, it was easier for the filmmakers to superimpose DeBose over DeBose, resulting in a disorienting effect. A moment later, she steps outside and sits down, and there’s some more ADR—this time delivered with a digitized mouth to fix whatever Calypso originally said when shooting this scene. What the filmmakers didn’t consider was that these corrective solutions, though cheaper than reshoots, would distract some viewers so much that whatever Calypso says wouldn’t register anyway.

But then, most of Kraven the Hunter features distracting choices. This is surprising, given director J. C. Chandor’s knack for thoughtful, character-driven storytelling in A Most Violent Year (2014). Whatever his qualities as a director, they have been eradicated by studio and franchise imperatives. Still, along with cinematographer Ben Davis and the editors, Chandor delivers a somewhat visually cohesive product next to Morbius and Madame Web. There isn’t a cut every millisecond; the action is easy to follow. However, the CGI is downright silly and never convincing, with Rhino looking like a gray digital blob and various wild beasts resembling the animals in Jumanji (1995). Moreover, the persistence of ADR, along with the production’s many reported delays and reshoots, suggests that the filmmakers neither had a vision nor took the necessary time to deliver a polished product. This is also Sony’s first Spider-Man adjacent movie with an R rating, and yes, its bloody body count and number of “fucks” prove high. But it takes more than a few gory bits and swear words to overlook this otherwise substandard execution.

If there’s anything admirable about Kraven the Hunter, it’s the unsubtle message against sport-hunting animals. Kraven doles out unsparingly bloody retribution for poachers and hunters after they’re caught slaughtering animals (the animal deaths are all CGI, but they’re no less difficult to watch). Kraven is an animal lover, and it’s his only sympathetic quality. There’s some poetic justice in Kraven’s vengeance against such people, reminiscent of when one of those wealthy trophy hunters on an African safari is trampled by an elephant or eaten by a lion. Nothing else registers or makes an impression in the movie. At least Venom or even Morbius might be fun enough to qualify as camp. With Kraven the Hunter, I sunk into my seat and groaned too often to recommend it, even ironically.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review