Reader's Choice

Kramer vs. Kramer

By Brian Eggert |

As someone writing about film in a time of political and social unrest, it’s tempting to read every new film as a metaphor for what’s happening in my country and throughout the rest of the world. Admittedly, it’s easy to see strains of Donald Trump in every villain or feel that films about mistreated women are somehow about the #MeToo movement. Perhaps that’s some sort of recency bias or confirmation bias on the part of myself and other critics who have, to some extent, interpreted newer releases from an extratextual and sociopolitical perspective. I have tried to stop myself from always going down this path, but occasionally it’s quite difficult.

Then again, I firmly believe that films don’t have to be about greater issues. Sometimes, films can just be stories. For instance, a film that depicts violent acts against women, such as a scene in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood when Brad Pitt brutally beats a woman to death, isn’t advocating violence against women, as some have written, nor is it commenting on the depiction of violence itself. It might be just something that happened in a particular story, a stylistic and dramatic flourish. When bad things happen in a film, sometimes it’s for purely artistic effect. Characters in films are not always representative of their entire group. The filmmaker may not intend their work to be seen as a cipher that, once decoded, will reveal a lesson about the way the world should be for a particular group or segment of our society. Some films set out to tell individual stories. Others set out to speak to themes in our society. Most films can be interpreted to either extreme.

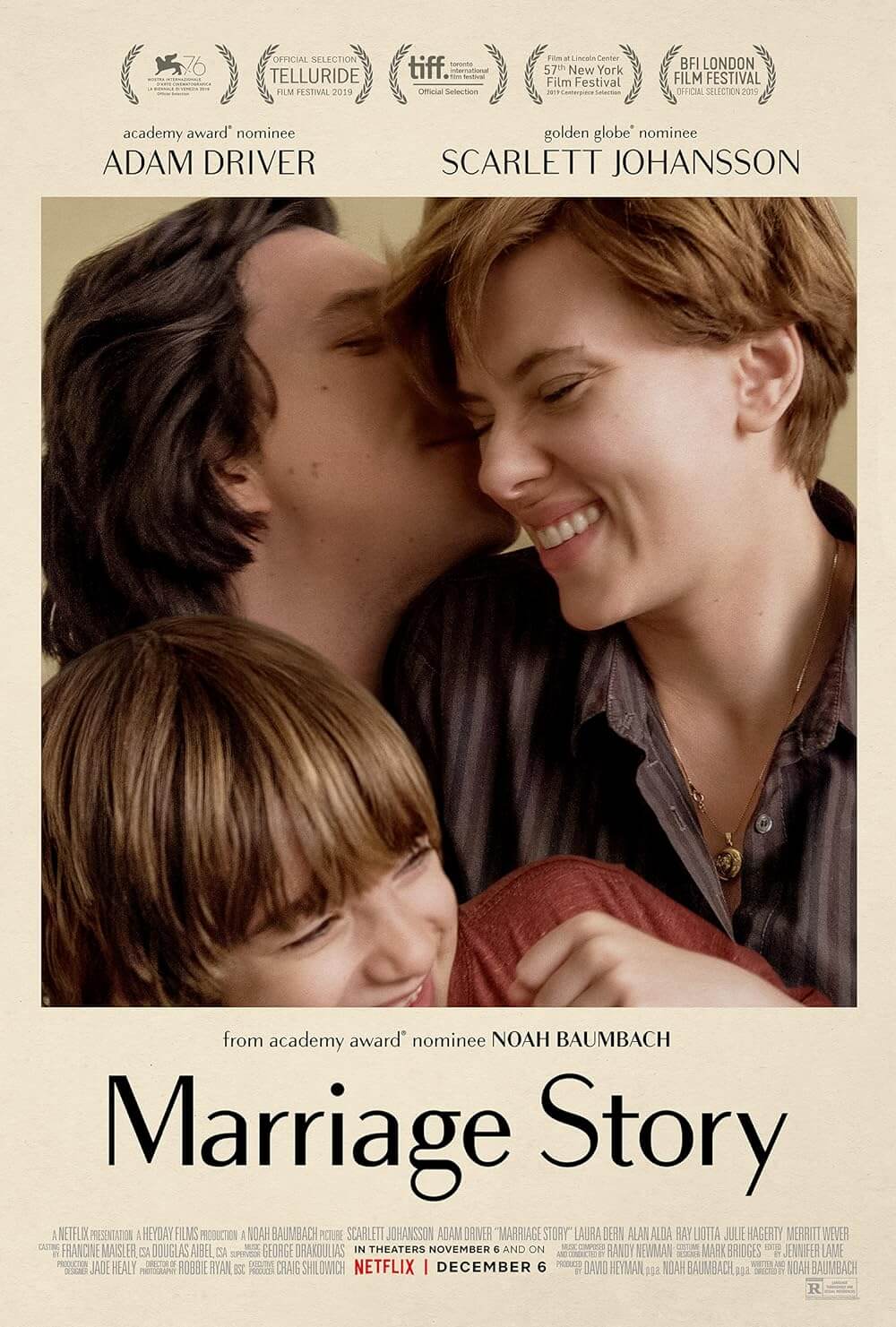

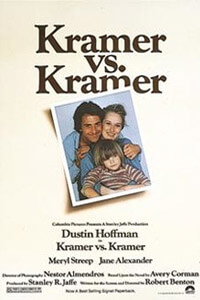

I raise these issues in this review of 1979’s Kramer vs. Kramer because it’s tempting to see the film as a story of a divorced couple who go to court to fight for custody of their child. Dustin Hoffman plays Ted Kramer, an advertising exec who works too much. Meryl Streep plays his neglected wife Joanna. Unhappy in their marriage, Joanna decides to leave Ted and their son Billy (an excellent Justin Henry). Joanna eventually divorces Ted and abandons her family for 18 months to find herself in California, while Ted is forced to parent Billy for the first time. The father and son form a bond, and Ted learns to place Billy above all other concerns in his life. If you’ve ever been through a divorce, or experienced a divorce from the child’s perspective, the film will resonate with you.

And while this brief description of the plot breaks down most of the film, there’s something else here too. When watching it for the first time a couple of weeks ago, something about the film seemed off to me. It caused me to raise an eyebrow on the initial screening, and since then, it has festered in the back of my mind, souring the experience. I couldn’t help but feel that the film demonized Joanna, who is absent for much of the first act and the entire second act of the film. At the same time, it seemed to use her as an excuse to strike a blow against “women’s lib,” a term that the film’s male characters only ever use in a pejorative sense. But maybe I was just viewing the film through the eyes of someone living through the #MeToo movement, where my critical eye has a heightened awareness and scrutiny of how filmmakers choose to represent women.

And while this brief description of the plot breaks down most of the film, there’s something else here too. When watching it for the first time a couple of weeks ago, something about the film seemed off to me. It caused me to raise an eyebrow on the initial screening, and since then, it has festered in the back of my mind, souring the experience. I couldn’t help but feel that the film demonized Joanna, who is absent for much of the first act and the entire second act of the film. At the same time, it seemed to use her as an excuse to strike a blow against “women’s lib,” a term that the film’s male characters only ever use in a pejorative sense. But maybe I was just viewing the film through the eyes of someone living through the #MeToo movement, where my critical eye has a heightened awareness and scrutiny of how filmmakers choose to represent women.

After all, Kramer vs. Kramer is a work of some renown. At the 1980 Academy Awards ceremony, it was nominated in nine categories, winning Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director for Robert Benton, Best Actor for Hoffman, Best Supporting Actress for Streep, and Best Adapted Screenplay for Benton. The film was also a major cultural marker, inciting conversation and debate about gender equality for men in divorce cases involving child custody. It was such a topic of conversation that this small, realistically depicted family drama became the top box-office performer in the U.S., earning over $100 million in receipts (which, for 1979, is incredible). Kramer vs. Kramer outperformed other films from 1979, including Alien, Apocalypse Now, Rocky 2, and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. And yet, given its subject matter, one suspects that if the film were released today, it would be relegated to Netflix or the Lifetime network.

Smelling something funny in Kramer vs. Kramer, I read some reviews from the period, almost all of which were positive, if not downright celebratory of the method-style acting by Hoffman, the naturalism of Henry, and the breakthrough by a little-known New York theater performer: Streep, who had just lost her partner John Cazale (The Godfather, Dog Day Afternoon, The Deer Hunter) to lung cancer. Such praise is understandable. The cast is terrific, bound to bring any viewer to tears more than once. But then I came across interviews with Avery Corman, who wrote the 1977 novel on which Benton based his screenplay. Corman said that his novel sought to expose the “toxic rhetoric” of feminists; he felt they had viewed men as “a whole bunch of bad guys.” The feminists were “too overheated about men,” he said. Kramer vs. Kramer was “an attempt to redress a wrong,” to show what feminists were really like, while at the same time showing that men could parent just as well as women.

Corman’s mission with the book, thus the film it seems, was to address how feminists could give up their so-called womanly duties in the home, abandon their family, yet still retain the legal rights over their children. Moreover, he portrays Joanna as indecisive and irresponsible, whereas Ted is shown to be a worthy father for their child. And while single fathers were not commonplace in the typical assignment of gender roles in the late 1970s, Corman is quick to congratulate Ted for taking on his parenting roles (for the first time since the child was born, apparently), whereas there’s no consideration of Joanna’s role as a parent. It’s expected of her; it’s exceptional for him. Rather, Corman censures Joanna for seeking some measure of fulfillment if it means sacrificing her family, despite the fact that Ted has been absent from his family to pursue his ambitions as an advertising exec. And when Joanna is pressed to get a job to prove she’s a suitable parent, she easily lands a career that earns more than her ex-husband, but she hardly receives any credit for that. It’s a film rooted in male exceptionalism.

What’s even more curious is that Streep refused to play Joanna unless Benton made changes to the script. Streep demanded that Benton alter the character from Corman’s book, which apparently portrayed Joanna as even more awful than the film treats her. Streep wanted more empathy for the feminist perspective, justifying her character’s choice to abandon the family to fulfill her sense of personhood, as opposed to depicting Joanna as “an ogre, a princess”—the words Streep used to describe Corman’s version of the character to American Film magazine. Benton’s alterations give Joanna some dimension, but not enough. She’s still a character that is an unknown, an Other, next to the men in the picture. Benton’s script gives us reasons that Joanna left her husband, but it doesn’t care enough to spend time with her to discover those reasons beyond a few expositional lines of dialogue. Instead, the film reserves all credit for Ted.

Looking at Kramer vs. Kramer, it’s a film designed to make a statement about feminism, specifically against feminism. It cheers on Hoffman’s character and the sacrifices he makes to become a responsible single father, but it fails to adequately acknowledge how Streep’s character has already made the same sacrifices—because those responsibilities are expected of her. Briefly, in the climactic court case, Hoffman’s character acknowledges that he should have been more attuned to his wife’s inner life, but the viewer has no sense of that inner life, and the final scenes in the film almost entirely negate this sentiment. It’s a film that must be admired for its performances and the three-dimensionality of the father-son relationship at the center. But it’s also a film that has an agenda—it’s not just a story about a divorce. It’s a film that looks feminism in the face and shouts, “But what about men?!” and “Men deserve to be acknowledged for their sacrifices!” This is hardly an ideal position to take in the 1970s or today. And though many films today receive unfair or unwarranted criticism for what they represent to society at large, it seems as though few have looked back at Kramer vs. Kramer and considered what it hoped to communicate beyond its drama about gender roles in America.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review