Kong: Skull Island

By Brian Eggert |

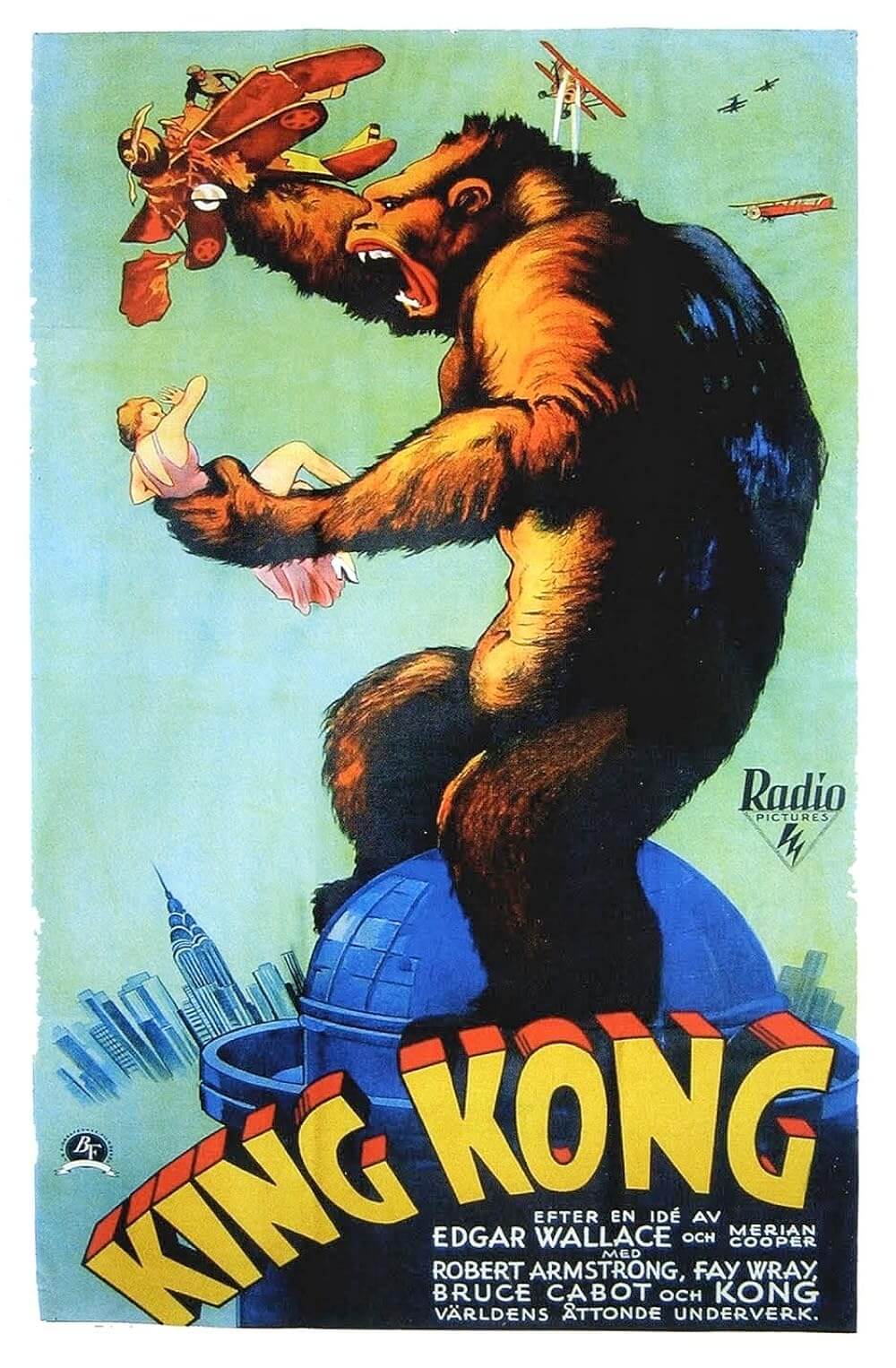

From the prologue onward, not a scene goes by in Kong: Skull Island without a discernible or obvious reference to another, better film. During the opening set in 1944 and “Somewhere over the South Pacific,” a dogfight between American and Japanese planes results in the two fighter pilots crashed on a mysterious island. The World War II opponents carry out their battle on foot, recalling Lee Marvin and Toshiro Mifune in Hell in the Pacific from 1968, until they’re interrupted by the towering figure any moviegoer recognizes: the iconic face of King Kong, the eighth wonder of the world. Director Jordan Vogt-Roberts proceeds with dozens of nods to other films throughout Kong: Skull Island, everything from the 1933 original to Oldboy. Hell, there’s even a Cannibal Holocaust reference.

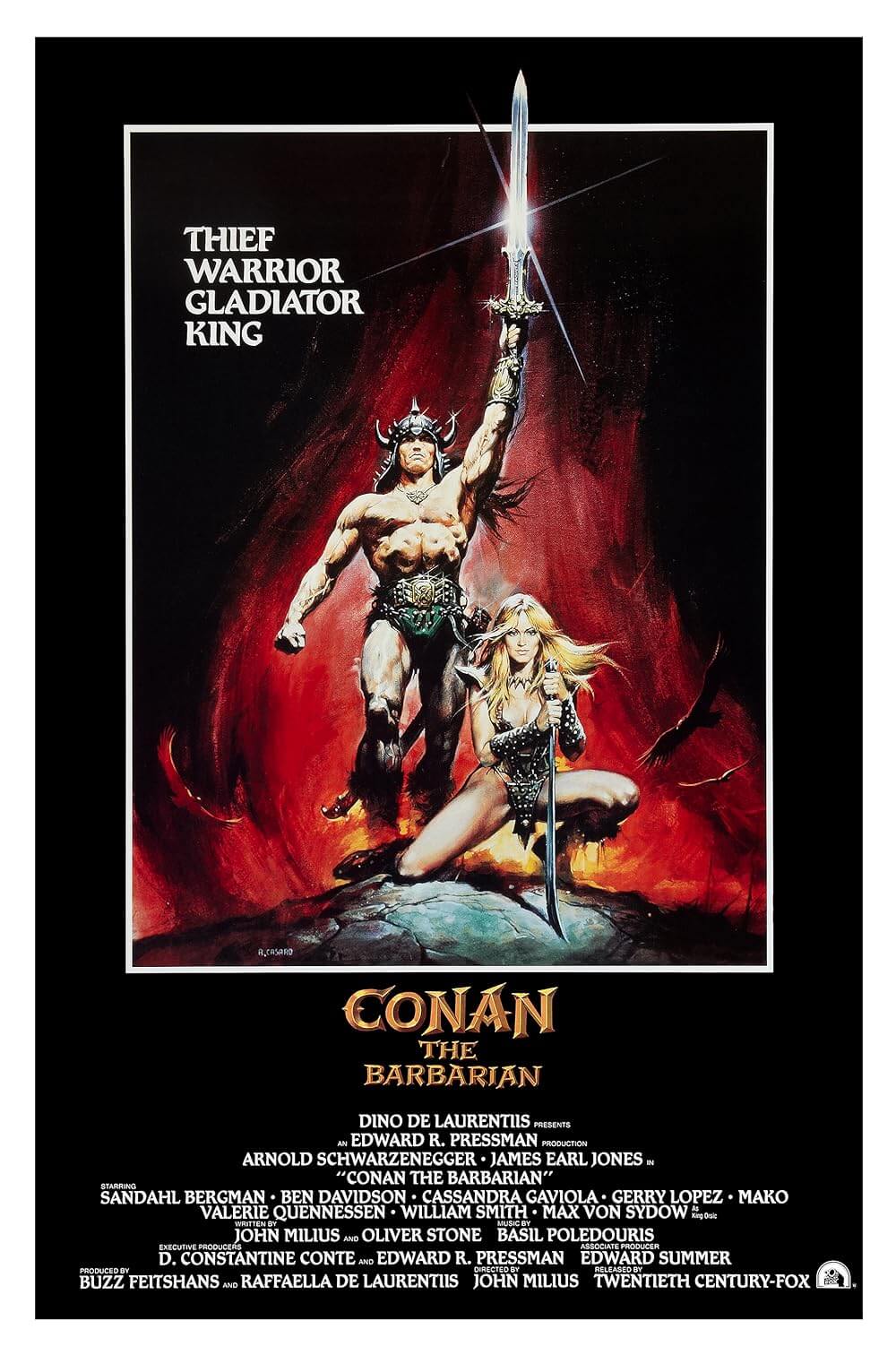

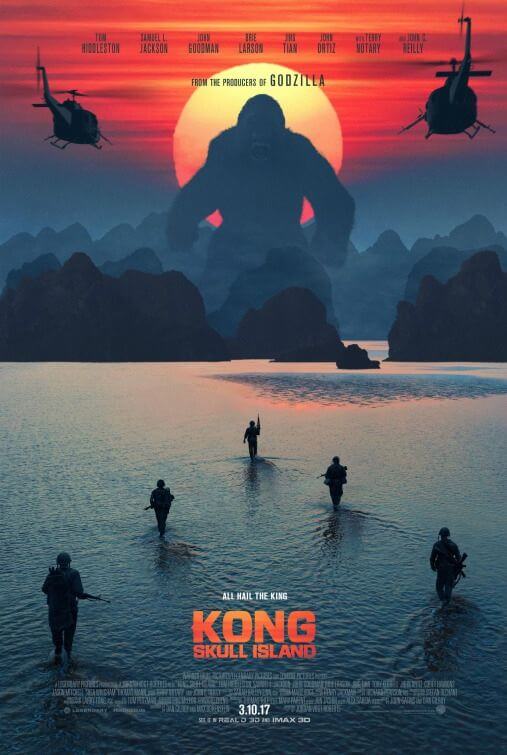

Listing each reference in context would amount to several paragraphs of explication, so let’s focus on the major ones. Vogt-Roberts, directing only his second feature here after The Kings of Summer (2013), seems intent on blending Apocalypse Now with an escapist monster-island tale of the Jules Verne variety—an unlikely pairing, to be sure. From scenes that silhouette a building-tall ape against a bright orange setting sun to an explosion of napalm along a tree line, Vogt-Roberts and his cinematographer Larry Fong rely on imagery from Francis Ford Coppola’s essential war film to inform the entire production. Consider the setting, which takes place in 1973, just days before the U.S. resolves to abandon the Vietnam conflict. A crew of scientists and war-torn grunts heads to the uncharted Skull Island in the South Pacific, led by an obsessed Colonel Packard (Samuel L. Jackson). There’s even a rugged British guide named Conrad (Tom Hiddleston).

Indeed, the nods to Heart of Darkness pervade (it’s any wonder why Packard isn’t named Kurtz). Along with antiwar photographer Mason Weaver (Brie Larson), the mission involves soldiers in a cadre of armed military helicopters escorting a group of scientists through the constant storm clouds that surround Skull Island. Once they break through, they study the terrain by dropping seismic bombs, thereby rustling Kong, who responds by batting the helicopters from the sky and killing most of the mission crew. Packard, none-too-happy about losing his men, confronts the mission’s brainchild: conspiracy fanatic Bill Randa (John Goodman), who believes our planet is home to giant monsters. Turns out he was right. But rather than study them, Randa wants to obliterate them, which Packard is only too happy to facilitate.

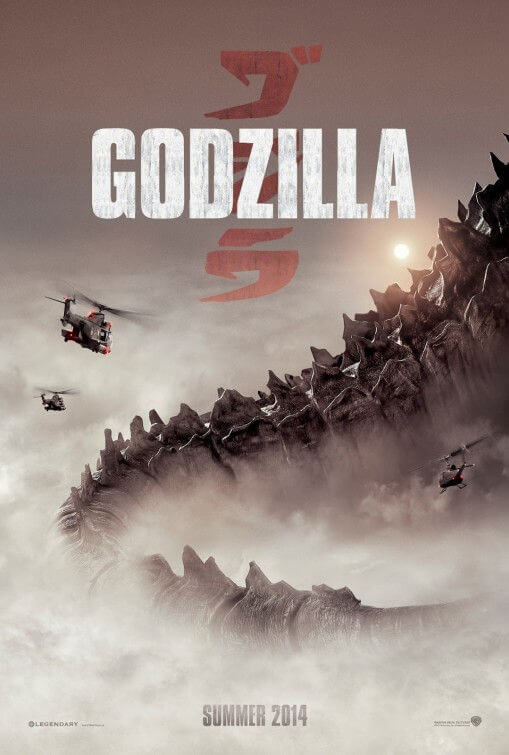

Kong, you will notice, stands upright like the original version, and nothing like the giant silverback gorilla in Peter Jackson’s underrated 2005 remake. Kong’s size has varied in his various iterations, but the reasons behind his ridiculously large presence in Kong: Skull Island is purely commercial. Warner Bros. Pictures has already staked their claim on the Japanese kaiju genre in 2013 with Guillermo Del Toro’s underwhelming Pacific Rim. And after Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla from 2014, the studio has unofficially announced plans to remake Toho’s ridiculous mashup King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962). However, the severe quality of Godzilla seems like an entirely different universe than the bonkers, tongue-in-cheek style of Kong: Skull Island. To ensure Kong can someday battle Godzilla, this film does not end with a fateful trip back to New York City and a fall from the Empire State Building; instead, Kong defends his island turf from invading humans and monsters.

Kong, you will notice, stands upright like the original version, and nothing like the giant silverback gorilla in Peter Jackson’s underrated 2005 remake. Kong’s size has varied in his various iterations, but the reasons behind his ridiculously large presence in Kong: Skull Island is purely commercial. Warner Bros. Pictures has already staked their claim on the Japanese kaiju genre in 2013 with Guillermo Del Toro’s underwhelming Pacific Rim. And after Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla from 2014, the studio has unofficially announced plans to remake Toho’s ridiculous mashup King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962). However, the severe quality of Godzilla seems like an entirely different universe than the bonkers, tongue-in-cheek style of Kong: Skull Island. To ensure Kong can someday battle Godzilla, this film does not end with a fateful trip back to New York City and a fall from the Empire State Building; instead, Kong defends his island turf from invading humans and monsters.

Even as he draws from Apocalypse Now, Vogt-Roberts adopts a contrarily corny tone, in particular after the survivors of Kong’s initial attack meet up with the stir crazy Hank Marlow (John C. Reilly), the prologue’s U.S. pilot who’s been stranded on the island since WWII. Marlow, pleased that the crew’s arrival means he might finally escape the island, also censures their use of the seismic bombs that opened craters into a vast subterranean habitat festering with enormous lizard-things—Kong’s natural competition on the island. As the humans travel across deadly terrain to make a brief rescue window, they face pterodactyls, humongous spiders, and other assorted creatures, and the CGI used to create them is serviceable at best. Meanwhile, Packard sees Kong as his own white whale, even though the giant ape may be their only protection against the lizard-things—hence the reason the locals worship him as a god.

Editor Richard Pearson keeps the proceedings fast-paced to a fault, cutting in a way that both prevents an immersive experience and defies logic (a silly thing to hope for in a giant ape adventure, I know). For instance, the characters often travel uncertain distances between cuts. Take a sequence after the crew narrowly survives a lizard-thing in an ape graveyard. Pearson cuts to the survivors in the woods, to where they have somehow escaped, and in their journey to safe terrain, none of them apparently mentioned the preceding events to one another. Then again, even after something amazing happens, the characters don’t talk about it or reflect with wonder; rather, they just remark, “Are we not going to talk about what just happened!?” in a typically modern ironic tone. Based on a story by John Gatnis, the screenplay (credited to Dan Gilroy, Max Borenstein, and Derek Connolly) uses contemporary colloquialisms that feel misplaced for a story set in 1973. In addition to the usual “I got this!” and “Let’s do this!” declarations prevalent in blockbuster cinema today, the characters talk in biting phrases and humor that seem incongruous with the film’s time and place.

After all, it’s easier to write kitschy dialogue than flesh-out characters, and Kong: Skull Island has no time for characterizations. The main cast is defined by their occupations: Jackson uses his usual screen persona under the pretense of a military man; Larson’s photographer is nothing more than a sympathetic face; and, strangely enough, the top-billed Hiddleston never has a Big Moment that justifies all the screenplay’s talk about his jungle tracker abilities. The rest of the talented cast provides body count fodder (among them are Shea Whigham, Toby Kebbell, John Ortiz, Corey Hawkins, Jason Mitchell, Jing Tian, and Richard Jenkins). Most of these strong supporting players die unceremoniously—thwapped by a rogue tail, chomped by a monster, or stomped by a huge foot—and the glib tone in which they die further contrasts the director’s stylistic Apocalypse Now influence in unwieldy ways.

After all, it’s easier to write kitschy dialogue than flesh-out characters, and Kong: Skull Island has no time for characterizations. The main cast is defined by their occupations: Jackson uses his usual screen persona under the pretense of a military man; Larson’s photographer is nothing more than a sympathetic face; and, strangely enough, the top-billed Hiddleston never has a Big Moment that justifies all the screenplay’s talk about his jungle tracker abilities. The rest of the talented cast provides body count fodder (among them are Shea Whigham, Toby Kebbell, John Ortiz, Corey Hawkins, Jason Mitchell, Jing Tian, and Richard Jenkins). Most of these strong supporting players die unceremoniously—thwapped by a rogue tail, chomped by a monster, or stomped by a huge foot—and the glib tone in which they die further contrasts the director’s stylistic Apocalypse Now influence in unwieldy ways.

Of course, Kong himself, portrayed by motion-capture actor Terry Notary, should be the most interesting character onscreen. But the monster has no more than a single dimension, that of Skull Island’s savage protector, while the two scenes where this beast defends Larson’s beauty remain so inconsequential and emotionally empty that it’s difficult to care. Compared to the complicated relationship between Kong and Fay Wray in earlier versions, well, there’s no comparison at all. Vogt-Roberts, with his highbrow film references and postmodern affectations, wants Kong: Skull Island to be more ambitious and thoughtful than it is. But a price tag of around $200 million and an impressive cast cannot distract from the production’s B-movie quality, nor the lack of sharpness and substance in the writing.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review