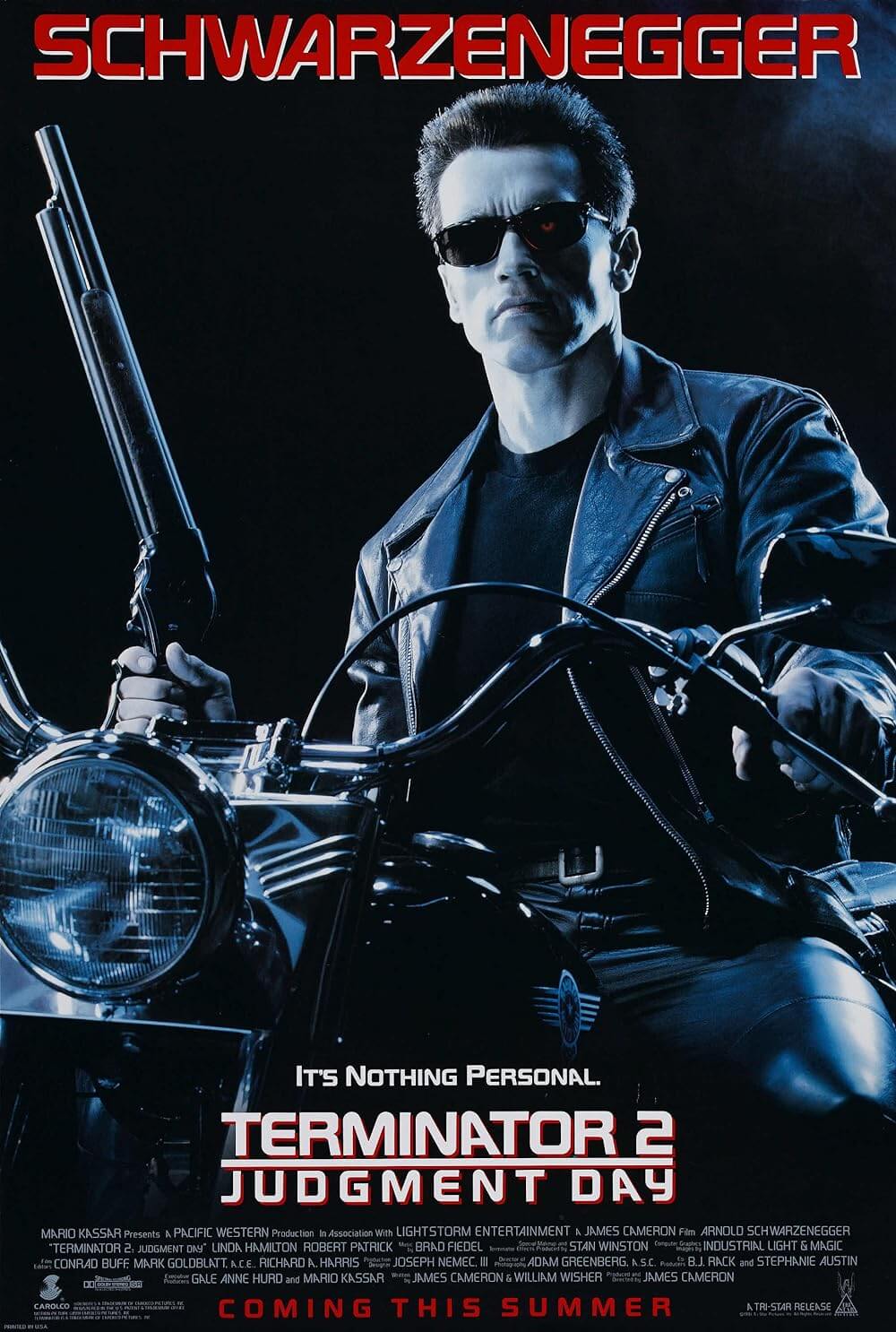

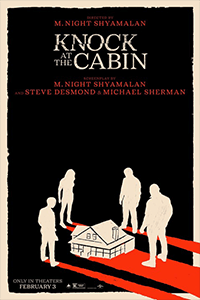

Knock at the Cabin

By Brian Eggert |

M. Night Shyamalan’s Knock at the Cabin is a terrific “What would you do?” movie. Here’s the setup: Your family rents a secluded cabin in the woods for a vacation. Suddenly, four strangers armed with makeshift weapons arrive and deliver some cockamamie news. They tell you the world will end unless your family sacrifices one of its own. Claiming to share apocalyptic visions, they demand you make the sacrificial choice, and if you refuse, they will kill one of their group in front of you. But each death from their party gives rise to a “plague” on the world, proven by suspiciously timed television news broadcasts. If you refuse to make a choice by the appointed time, all of humanity will be wiped out, and your family will be condemned to walk the scorched earth alone for eternity. At least, that’s what the deadly serious, possibly maniacal doomsayers claim. So what would you do? Would you believe the strangers and sacrifice a loved one to save the world? Or would you remain a skeptic and risk condemning every human being on the planet? You’ll ask yourself those questions after the movie, which is one of Shyamalan’s most satisfying in over twenty years.

His fifteenth film as director, Shyamalan’s body of work remains hit-or-miss, with most falling into the latter category. After his breakthrough with The Sixth Sense (1999), the filmmaker’s critical and box-office record has been wildly uneven, rarely living up to his personal brand. Over the years, his budgets have decreased from the $70-150 million range (on stinker productions like The Last Airbender, 2010) to his recent streak at Universal Pictures, where his smaller budgets—around $10 million and under for films such as The Visit (2015) and Split (2016)—translate to higher profit margins. That’s probably best since Shyamalan seems to thrive under budgetary limitations. This is especially true of Knock at the Cabin, a (mostly) single-location movie that cost $20 million to produce. It’s an old-school thriller, complete with a vintage Universal logo and a score by Icelandic composer Herdís Stefánsdóttir that evokes Bernard Herrmann. And true to Shyamalan’s self-made reputation as a modern-day Hitchcock, his latest is suspenseful from start to finish. He even sticks the landing—arguably, anyway.

Shyamalan based his script on Paul G. Tremblay’s book The Cabin at the End of the World (a better title), which he adapted alongside Steve Desmond and Michael Sherman. The script takes some liberties with the source material, but that won’t stop unfamiliar audiences from engaging with the irresistible premise. The story opens with Wen (Kristen Cui), a young girl on vacation with her dads, Eric (Jonathan Groff) and Andrew (Ben Aldridge). Outside in the woods, Wen catches grasshoppers when a towering Dave Bautista approaches her and introduces himself as Leonard. Although Leonard behaves kindly enough, his talk of making “new friends” and playing a game raises our internal alarms. Shyamalan and cinematographer Jarin Blaschke (usually paired with Robert Eggers) shoot the scene with a two-shot close-up, where both characters look directly into the camera—a tactic Shyamalan learned from his three-time cinematographer Tak Fujimoto, who developed the technique with Jonathan Demme (The Silence of the Lambs, 1991). With the ever-tilting Dutch angles, the increasingly edgy scene soon reveals that Leonard isn’t alone—he’s with three others, and they need Wen’s family to “save a whole bunch of people.”

Although Wen seems like she should have been shouting “stranger danger” much sooner, she eventually alerts her dads that trouble’s coming. They put up a brief fight, and Eric is hit in the head, resulting in a concussion. Before long, the couple is tied to chairs with rope, with Wen free to alternate between them. Convinced they’re about to be victims of an anti-gay crime, Eric and Andrew listen as four average-looking people who appear to be reluctant intruders explain the stakes outlined in the first paragraph of this review. They also introduce themselves: Leonard claims to be a second-grade teacher; Sabrina (Nikki Amuka-Bird) is a nurse; Adriane (Abby Quinn) is a line cook and mother of a small boy; and Redmond (Rupert Grint, delivering an iffy New England accent) works for a power company. They all seem like amiable, down-to-earth people, except they believe crazy things. At least, that’s what Andrew, a litigator and staunch realist, believes. Eric, the more religious of the two, becomes more unsure of what to think as the movie progresses. And that illuminated figure Eric saw in a mirror—was that a result of his concussion or an actual religious experience?

Although Wen seems like she should have been shouting “stranger danger” much sooner, she eventually alerts her dads that trouble’s coming. They put up a brief fight, and Eric is hit in the head, resulting in a concussion. Before long, the couple is tied to chairs with rope, with Wen free to alternate between them. Convinced they’re about to be victims of an anti-gay crime, Eric and Andrew listen as four average-looking people who appear to be reluctant intruders explain the stakes outlined in the first paragraph of this review. They also introduce themselves: Leonard claims to be a second-grade teacher; Sabrina (Nikki Amuka-Bird) is a nurse; Adriane (Abby Quinn) is a line cook and mother of a small boy; and Redmond (Rupert Grint, delivering an iffy New England accent) works for a power company. They all seem like amiable, down-to-earth people, except they believe crazy things. At least, that’s what Andrew, a litigator and staunch realist, believes. Eric, the more religious of the two, becomes more unsure of what to think as the movie progresses. And that illuminated figure Eric saw in a mirror—was that a result of his concussion or an actual religious experience?

For most of Knock at the Cabin, the home invasion scenario takes us from skeptical to indecisive about the intruders’ claims. Are they mere zealots acting on a shared delusion after meeting on a message board (always a bad sign)? While the viewer processes their story, our sympathies lie with the family. Shyamalan and editor Noemi Katharina Preiswerk deepen the genuine relationship between the impressionable Eric and the hair-trigger Andrew with flashbacks that explore their bond—the difficulties they faced with their parents when getting married, their choice to adopt Wen—all accented with their mantra, “Always together.” These layers also develop Eric and Andrew so that their behavior has an emotional logic when the finale arrives. Both actors perform splendidly in their roles, with the showier role falling to Aldridge, whose open-hearted presence recalls his part in last year’s Spoiler Alert. Bautista uses his sheer mass to appear intimidating, but he gives a sensitive turn that’s unlike any actionized fare the former wrestler has delivered before.

Like many Shyamalan movies, Knock at the Cabin rests on its ending (if you want to remain spoiler-free, skip to the next paragraph). Fans of the book may feel that Shyamalan undoes what, in novel form, confronted the reader with unanswered questions. Tremblay established the same basic scenario as Shyamalan’s movie, but his conclusion is open-ended and doesn’t cater to the masses as Shyamalan’s does. Although I won’t divulge exactly how Shyamalan resolves the central conflict, I will say that he provides answers and takes an ideological side. It’s a choice that proves audience-friendly and leaves little doubt about the questions we’ve asked throughout the movie. Ultimately, it’s disappointing that Shyamalan didn’t make something more ambiguous—after all, the unknown is always more frightening, as evidenced by Rose Glass’ similarly themed Saint Maud (2019). But Shyamalan’s choices remain unsurprising. He’s no stranger to religious themes in his movies—just watch the pointed Signs (2002), whose title refers to both alien-made crop circles and messages from God. Instead, by the end, Knock at the Cabin plays like the religious crackpot movie America doesn’t need right now, suggesting that the mad prophets are right, their violent behavior is justified, and that we would all do well to listen to them—a scary notion, to be sure.

Knock at the Cabin comes oh-so-close to eviscerating the audience with an equivocal ending, but instead, Shyamalan makes up the viewer’s mind for them. That’s not an inherently bad choice. For instance, writer-director Frank Darabont adapted Stephen King’s novella The Mist, which ended in obscurity, and came up with a shocker ending to his 2007 film that avoided ambiguity but left the viewer memorably shaken. Shyamalan isn’t as gutsy a filmmaker as Darabont, and he won’t risk pissing off a large segment of his audience by challenging them or robbing them of catharsis. But if I set aside my atheistic reservations and the filmmaker’s pandering, and I consider what’s onscreen instead of what could have been onscreen, it’s easy to recognize what a well-executed film Shyamalan has made. From start to finish, Knock at the Cabin ensnares the audience in a tense scenario with assured direction. The director manipulates his viewer with fluid camera moves and strained situations, and he commands impressive performances from the cast, in particular Aldridge, Bautista, Groff, and the newcomer Cui. No matter how you might feel about the ending, Shyamalan delivers one of the best films of his career and reminds us that it’s worth enduring his many misses for an occasional hit this good.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review