Knives Out

By Brian Eggert |

Rian Johnson thrusts the viewer into a murder mystery with Knives Out, a terrifically entertaining whodunit that revels in clever gamesmanship. The venerable Agatha Christie formula, where a crime is committed among wealthy elitists and an intelligent detective, bedecked in tweed, must uncover the answers, comes to vivid and breathless life in Johnson’s capable hands. It’s a keeps-you-guessing spin through suspicious testimony and unpredictable plot developments, treated with a deft touch and acted by an impressive cast, all of whom appear to be having a great time in their roles. And though it’s a dusty genre set predominantly in a large country estate, decorated with enough old trinkets to fill a cabinet of curiosities, the film has a decidedly modern angle about America in 2019. Knives Out carves into class and prejudice, supplying the viewer with more than an escapist thrill ride but a rousing political statement. Johnson’s sardonic and winking approach—playful for enthusiasts of Christie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, or even Jessica Fletcher—may not easily reveal its culprit, but its message remains palpable and crowd-pleasing, at least for those not on the sharp-end of the film’s dagger.

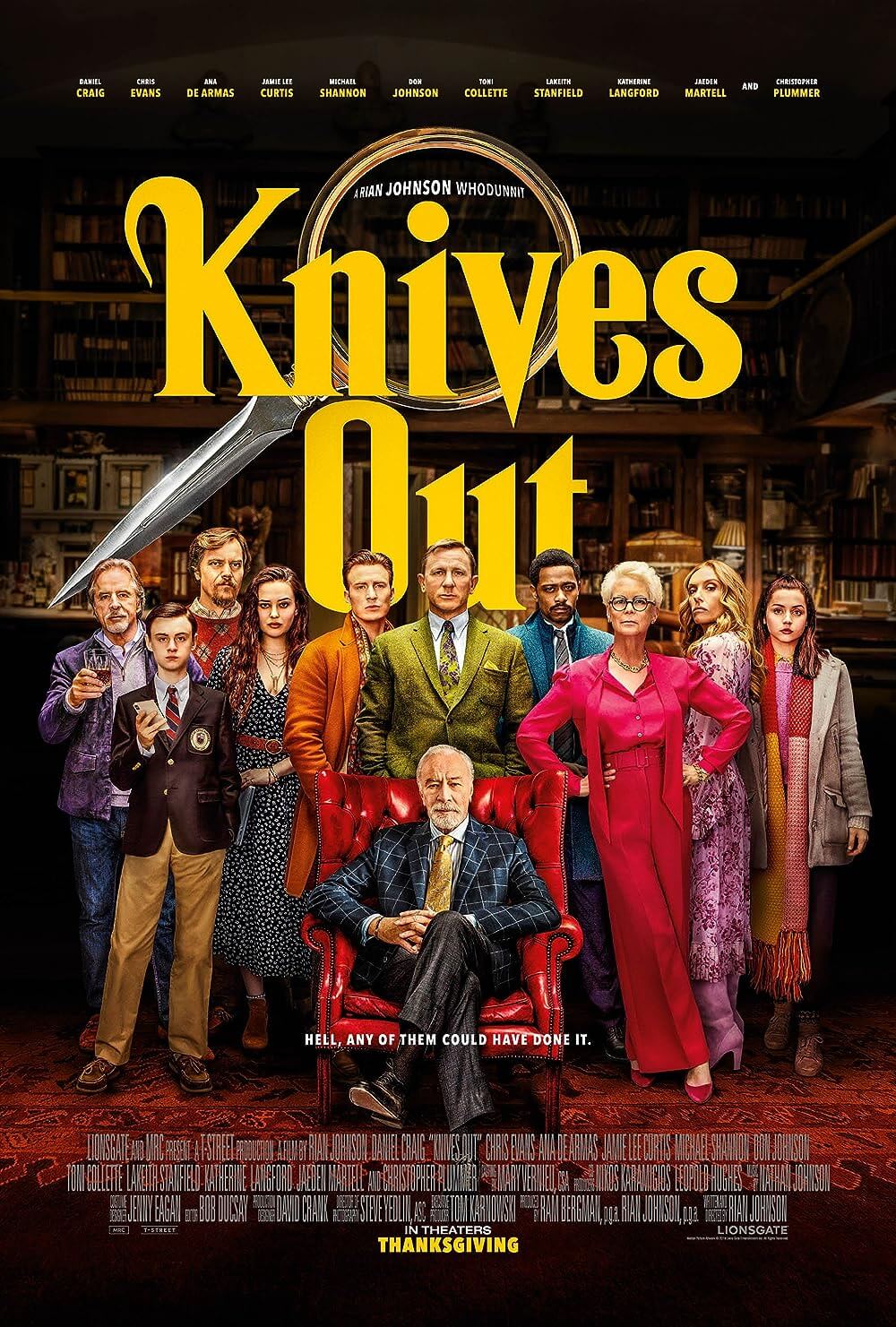

Harlan Thrombey (Christopher Plummer) is dead, to begin with. The novelist built an empire out of best-selling murder mysteries, but just after his 85th birthday party, attended by all of his nouveau riche children, their spouses, and his grandchildren, the author committed what appears to be suicide. He was found in his study with his throat cut, and crime scene investigators confirmed that it was a self-inflicted wound to the neck. If that’s the case, however, then why has someone anonymously hired Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig), the renowned private investigator with a Foghorn Leghorn accent and penchant for long cigars, to investigate Harlan’s death as a murder? Unsure of who hired him, Blanc, his curiosity piqued, joins two detectives (Lakeith Stanfield, Noah Segan) to re-interview the Thrombey family, who anxiously await the reading of the patriarch’s will. Each family member must submit to an interview conducted by the detectives, while Blanc watches (“A passive observer,” he says, “of the truth”) from the back of the room, tapping a piano key to signal when he wants the officers to ask a particular question.

Johnson introduces us to the Thrombeys, a narcissistic and entitled bunch, through their occasionally Rashomon-like accounts of the birthday party. Walt (Michael Shannon), Harlan’s youngest son who runs the publishing company that distributes his father’s books, is married to Donna (Riki Lindhome), and they have an alt-right son (Jaeden Martell). Harlan’s eldest child, Linda (Jamie Lee Curtis), considers herself a self-made woman and owner of a successful real-estate business, which she started after a considerable loan from her father (Sound familiar?). Generally cross and sarcastic, Linda is married to the dopey Richard (Don Johnson), and their son, Ransom (Chris Evans), the black sheep of the family, didn’t bother showing up for Harlan’s funeral. Lastly, there’s Joni (Toni Collette), the widow of Harlan’s deceased son, who promotes herself as a “lifestyle guru” but still needs regular payments from her father-in-law to pay the expensive tuition for her activist daughter (Katherine Langford). Each of them had a conflict with Harlan about the same problem: inheritance. “My mind’s made up,” he tells his children one by one, after resolving to cut them off from financial support. He wants each of them to persevere through hardship, but they’d prefer their cushy lifestyle of monthly allowances. In other words, everyone has a motive.

At the end of the first act, however, Knives Out reveals what happened to Harlan, or at least what appears to have happened, and the structure shifts from a whodunit to something more nimble and reliant on forward momentum, as opposed to testimony and flashbacks. Harlan’s good-natured nurse and friend, Marta (Ana de Armas), moves from the periphery to the center of the story. As the only one expressing real grief over Harlan’s death, the family appreciates her presence, though she wasn’t invited to the funeral; each of the Thrombeys claims to have been “outvoted” by the others over whether to invite her. In a cruel running gag, Marta and her family emigrated from a Latin American country the Thrombeys can’t be bothered to remember (Uruguay or Paraguay, Brazil maybe), and they frequently refer to her as “the help.” They claim to consider her “part of the family,” though it’s a hollow status given by white liberal racists. In one sly moment, Richard hands her a plate, as if she’s a servant and not Harlan’s nurse. As for Blanc, he sees Marta for her genuine sweetness, which is punctuated by a striking personality quirk: she cannot tell a lie, and if she tries, her conscience will force a vomit reflex.

At the end of the first act, however, Knives Out reveals what happened to Harlan, or at least what appears to have happened, and the structure shifts from a whodunit to something more nimble and reliant on forward momentum, as opposed to testimony and flashbacks. Harlan’s good-natured nurse and friend, Marta (Ana de Armas), moves from the periphery to the center of the story. As the only one expressing real grief over Harlan’s death, the family appreciates her presence, though she wasn’t invited to the funeral; each of the Thrombeys claims to have been “outvoted” by the others over whether to invite her. In a cruel running gag, Marta and her family emigrated from a Latin American country the Thrombeys can’t be bothered to remember (Uruguay or Paraguay, Brazil maybe), and they frequently refer to her as “the help.” They claim to consider her “part of the family,” though it’s a hollow status given by white liberal racists. In one sly moment, Richard hands her a plate, as if she’s a servant and not Harlan’s nurse. As for Blanc, he sees Marta for her genuine sweetness, which is punctuated by a striking personality quirk: she cannot tell a lie, and if she tries, her conscience will force a vomit reflex.

Knives Out bears inevitable comparisons to Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot novels, with Blanc as the resident, almost mythical detective, complete with eccentricities and comic mannerisms to spare. Johnson’s characters remain ever-aware that they’ve been locked inside a whodunit, as the brief reference to Murder, She Wrote indicates. Similarly, Stanfield’s detective observes of the Thrombey home that Harlan “practically lives on a Clue board,” while Blanc refers to Marta as the Watson to his magnifying-glass-using Sherlock. Even as Johnson employs the tricks of the murder mystery trade, he subverts them. It’s a tactic he’s used since his debut film, Brick (2005), a film noir set on a high school campus, where he occupies a genre but also dissects it from the inside-out. In 2008, he made Brothers Bloom, a Mamet-style lark about upended grifters and con-artists. His 2012 masterpiece Looper rethought the shifting timelines and sympathies of a futuristic time-travel thriller. Most recently, Johnson’s willingness to take apart in a genre was misapplied to Star Wars: Episode VIII – The Last Jedi (2017), much to the dismay of fans who felt his innovations were deviations from foundational aspects of George Lucas’ franchise. Indeed, Johnson’s best work seems to be outside of established intellectual properties, where he’s free to experiment and question the status quo without tarnishing a continuity.

Another filmmaker’s treatment of the same material might make us feel discombobulated, especially in the last twenty minutes or so of Knives Out. But Johnson makes the shifting theories and various switcheroos crackle with wit and clarity. He avoids luxuriating in the glorious setting and interior spaces, though there’s plenty to admire about David Crank’s production design. Red-painted shelves filled with books and trinkets, hidden passageways accented by telling artwork, hallways lined with expensive rugs and vintage magician posters, and the most pivotal prop: a round sculpture adorned with knives of every sort, pointed inward toward an empty center. Johnson and his regular cinematographer Steve Yedlin avoid any distracting visual flourishes, and the occasional cocked angle or dramatic push of the camera serves the story and its sometimes cheeky quality. The comic undercurrent of Knives Out makes the viewing experience a delight, especially when it comes to Craig, who, similar to his turn in Logan Lucky (2017), reveals his charm when he’s not reduced to the humorless 007.

The film would have been mindless fun had Johnson only just playfully navigated whodunit terrain, but it’s also surprisingly political, beginning with a tense conversation about the divisive, albeit unnamed, President of the United States and his MAGA policies. By aligning with Marta, Knives Out recalls Johnson’s work on The Last Jedi, in that he focuses on the marginalized class to understand a familiar story from an alternative perspective. In turn, this reformats the genre altogether, imbuing it with a rousing breakdown of America’s class, power, and economic dynamics. Once Marta becomes our clear protagonist, the film begins to recall Get Out (2016), with its well-heeled elitists who claim, “I would have voted for Obama for a third term,” despite harboring unimaginable secrets. To be sure, the specific murderer gradually becomes less important than the pure villainy of the Thrombey family as a whole. And in the end, Johnson brings the conflict between Marta and the family to a pitch-perfect conclusion, culminating with one of the year’s best last shots.

The film would have been mindless fun had Johnson only just playfully navigated whodunit terrain, but it’s also surprisingly political, beginning with a tense conversation about the divisive, albeit unnamed, President of the United States and his MAGA policies. By aligning with Marta, Knives Out recalls Johnson’s work on The Last Jedi, in that he focuses on the marginalized class to understand a familiar story from an alternative perspective. In turn, this reformats the genre altogether, imbuing it with a rousing breakdown of America’s class, power, and economic dynamics. Once Marta becomes our clear protagonist, the film begins to recall Get Out (2016), with its well-heeled elitists who claim, “I would have voted for Obama for a third term,” despite harboring unimaginable secrets. To be sure, the specific murderer gradually becomes less important than the pure villainy of the Thrombey family as a whole. And in the end, Johnson brings the conflict between Marta and the family to a pitch-perfect conclusion, culminating with one of the year’s best last shots.

Taking a cue from Sidney Lumet’s adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express (1974), Johnson avoids a significant pitfall of murder mystery casting by saturating his film with an all-star roster. Sometimes films of this sort give the killer away by placing a major performer in a minor role, which tells the audience that the character is more significant than their role initially appears. Knives Out has a dream cast of credible actors who chew the scenery in their equally limited scenes. From Jamie Lee Curtis to Michael Shannon to Chris Evans, it could be any of them. And in a way, watching these performers delight in their juicy roles becomes more enjoyable than uncovering the mystery. Of course, the unlikely standout among them is de Armas, best known for her heartbreaking supporting role in Blade Runner 2049 (2017) as a hologram companion with a soul. In a star-making performance, her character is filled with earnest humanity, and she outshines a cast populated by leads. Alongside Craig’s dogged and eccentric inspector, the two make for an endearing team of sleuths.

Sharp and funny, Knives Out exceeds expectations by proving to be more than its surface implies, even as Johnson demonstrates his first-rate skill in the story’s maneuvers and charades. It’s an expertly crafted and borderline satiric puzzle, which Blanc compares to a donut (he’s determined to find “the donut hole for the donut’s hole”). If not for de Armas’ genuinely affecting performance and her character’s revealing arc, the material might feel like pure pastiche. Instead, it’s a film whose substance deepens as its class-consciousness emerges, recalling recent films like Parasite and Hustlers, where our empathy lies with those struggling to get ahead in systems defined by nepotism, elitism, and racism. What’s so impressive about Knives Out is how well Johnson balances raw entertainment value with his commentary. Even as he thrills his audience with a suspenseful and often laugh-out-loud take on the whodunit genre, which usually takes place in the world of stuffy and unrelatable elites, Johnson makes the material relevant—and there’s something magnificent about that.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review