Knight of Cups

By Brian Eggert |

Blending an old world tale involving a knightly quest with the mysticism of tarot cards, Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups tells a Prodigal Son parable in a debauched West Coast setting. This unlikely, strange juxtaposition of old and new characterizes Malick’s film from the first moments onward, giving way to another of the filmmaker’s ponderous, transcendent experiences the audience must feel to truly appreciate. Whether one relates to this pointedly male-centric, arguably autobiographical story depends on the viewer’s willingness to decipher two hours of visual metaphors, roving camerawork, a minimum of plot, and very little dialogue—all within a nonlinear structure. Although an overt classicism takes hold early on as we hear John Gielgud read from The Pilgrim’s Progress, the film also considers the post-modern splendor of a hypnotic satellite’s-eye-view of the aurora borealis. Already there’s much to think about, and this is just in the first few seconds of screentime.

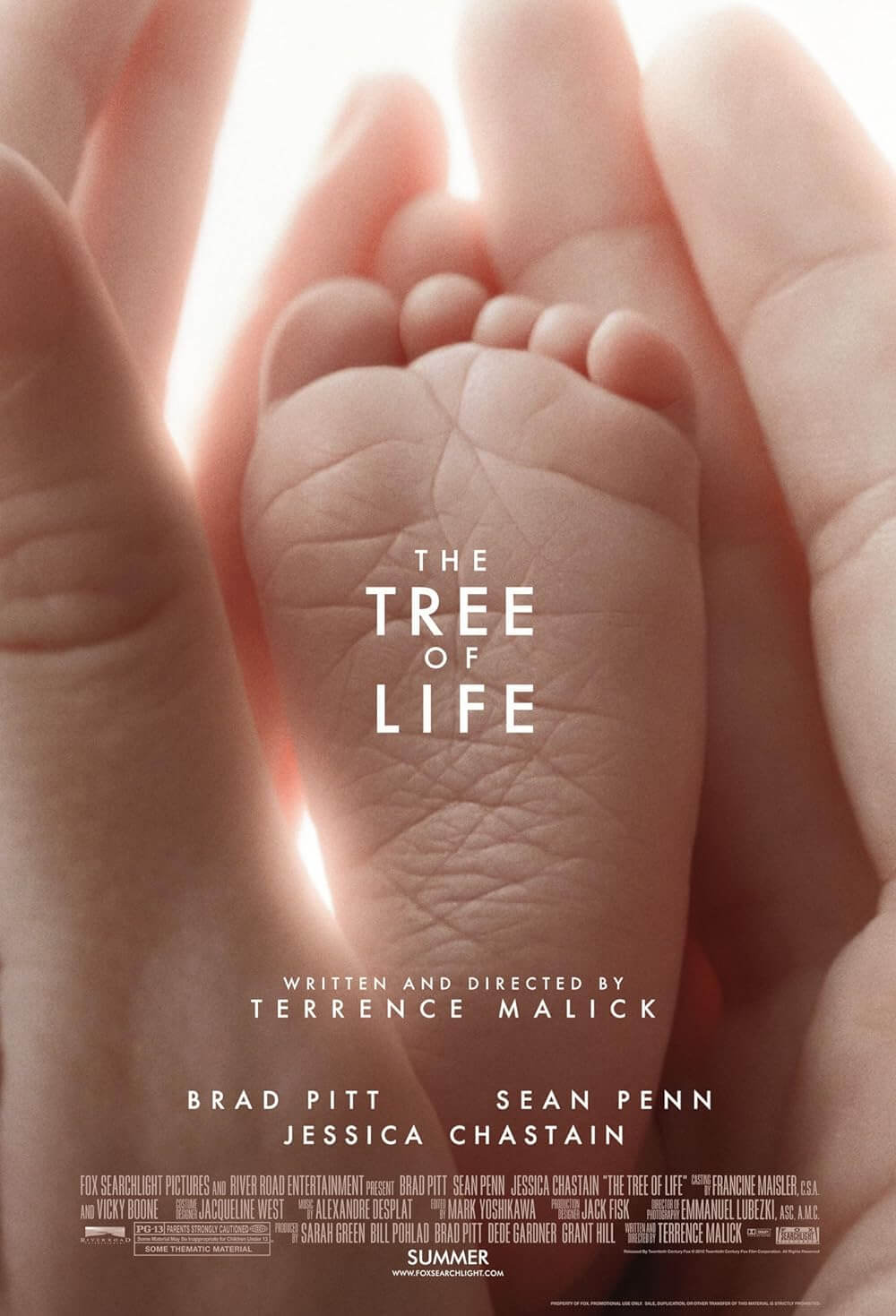

A reclusive filmmaker whose motion pictures play like living poems, wherein philosophical voiceover accompanies breathtakingly gorgeous imagery, Malick explores his boundaries in this, his seventh film in forty-three years. Whereas his first four works each considered specific historical periods from a 1916 Texas farm in Days of Heaven (1978) to the Guadalcanal Campaign in World War II for The Thin Red Line (1998), Knight of Cups finds locations in Caesar’s Palace, Los Angeles strip clubs, posh Hollywood parties, and a fashion shoot—where a photographer instructs her subject to be “like a ‘50s housewife who fucks teenage girls during the day.” Only recently has Malick set his pictures in the contemporary world, beginning with Sean Penn’s scenes in The Tree of Life (2011) and then the modern-day setting of To the Wonder (2013).

Knight of Cups is something altogether uncommon for Malick, saturated in westernized bacchanalia, yet telling a traditional, Old English kind of story. In voiceover, Brian Dennehy’s father character recounts the titular fable: When his father the King sends him on a quest to find a pearl, a Knight from the East journeys westward to a far-away land. Upon his arrival in the West, he drinks from a cup, the contents of which make him forget the purpose of his journey. Christian Bale plays Rick, the knight of this tale. He’s a screenwriter who has long since lost himself and the reasons for his journey. Having become swept up in la dolce vita in L.A., Rick left his wife (Cate Blanchett), his veritable pearl, in favor of empty experiences and the lure of Hollywood’s false promises. Most of the film takes place during Rick’s state of displacement, drifting in and out of his memories, reveries, regrets, and existential crises.

After Rick receives a reading early in the film, he and those around him are defined through tarot cards, the names of which appear onscreen as episodic titles. One of his two brothers (the other is played by Wes Bentley) died tragically young, the aftermath of which is recalled in “The Hanged Man” episode. Other titles such as “The Hermit” for Antonio Banderas’ wild playboy, or “The High Priestess” for Teresa Palmer’s blithe stripper with an anything-is-possible worldview, offer insight into the later cards of “Death” and “Freedom”. Meanwhile, Rick takes on a series of random, often meaningless sexual conquests, and tries desperately to make connections to a series of women: Imogen Poots appears as a rebellious type, Freida Pinto plays a young model, and Natalie Portman plays a married woman—and each sees Rick as a broken man. He doesn’t seem to be treating them as objects, at least; just people to whom he’s impossibly trying to make a meaningful connection.

To be sure, Rick remains in a constant state of searching. Desperate to feel something, he attends wild parties and experiences his life as a whole like a flâneur in the Baudelaire sense—wandering through and observing from a distance. He passes by a myriad of notable celebrity cameos (Ryan O’Neal, Jason Clarke, Joe Manganiello, Thomas Lennon, Nick Kroll, etc.) unfazed, window shops along various L.A. streets without any particular interest, and walks along Venice beach in a crowd like a ghost. At other times throughout the film, Rick walks through barren terrain or along a beach, always at the magic hour, Malick’s favorite time to shoot because the lighting is spectacular, as is apparent throughout the film. Though Bale’s character is supposedly a screenwriter (of comedies no less) on the cusp of a great success, he’s never shown working or writing, and the few business meetings he has on studio lots show him uninterested. The actor habors a kind of bemused sadness with him throughout, leaving his character feeling somewhat impenetrable, but no less emotionally sonorous.

Many of these story details must be gleaned from cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki’s nomadic camera, gliding within the spaces around the actors and following their discordant patterns of searching, often playful movement. Shooting almost exclusively in wide-angles and using a varied array of cameras (35mm, 65mm, digital), Lubezki captures Rick’s probing inner state. There’s a sense of feeling lost and trying to figure things out within the camerawork, just as there are passages where Rick looks on a sight of natural beauty and appreciates it. His appreciation of Nature suggests he wants the same singularity for his own life. All the while, Malick’s preferred mode of relating narrative details is voiceover, spoken largely in whispered, elegiac verses uttered by others to Rick. With dialogue sparse and in many cases turned low or inaudible, the soft narration offers a simple, familiar story on profound terms.

Though Knight of Cups contains a number of familiar Malickian devices and techniques, the setting remains modern and somehow more urgent than his films after The New World (2007). One can only speculate as to the autobiographical significance of the narrative, as if such things matter. However, a grave sense of regret flows through the picture, perhaps recounting, quite unsympathetically, Malick’s own experiences in Hollywood, feeling lost in several “developmental hell” projects over the years, and the great toll such experiences took on his personal relationships. This is purely speculation, of course; still, the material feels more personal than any of his works since Badlands (1973)—and more experimental. Placed alongside the delicate orchestral score and ambling shots of landscapes are the thumping beats of dance music, neon lights, and occasionally manic editing (by Geoffrey Richman, Keith Fraase, and A.J. Edward). More than one sequence feels like a montage put together for a museum of modern art.

Whether the spiritual journey belongs to Rick, the film’s director, or its audience, Knight of Cups transfixes the viewer in beautiful images and a spare, deeply felt narrative simplicity. Of course, most audiences will never see this relatively small independent film, and if they do, they will probably describe it as boring or aimless, regardless of the all-star cast. Even the majority of critics found Knight of Cups lumbering and indecipherable, whereas Malick’s efforts usually earn the highest assessments. But this film’s meditative quality, resistance to narrative exposition, and formal experimentation have an interesting place in Malick’s body of work, and much like To the Wonder, it defies most requirements of commercial cinema. Rather, Knight of Cups achieves a similar emotional perceptibility as the director’s earliest narrative films, and expects us to feel everything onscreen in the way great works of art often do.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review