Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

By Brian Eggert |

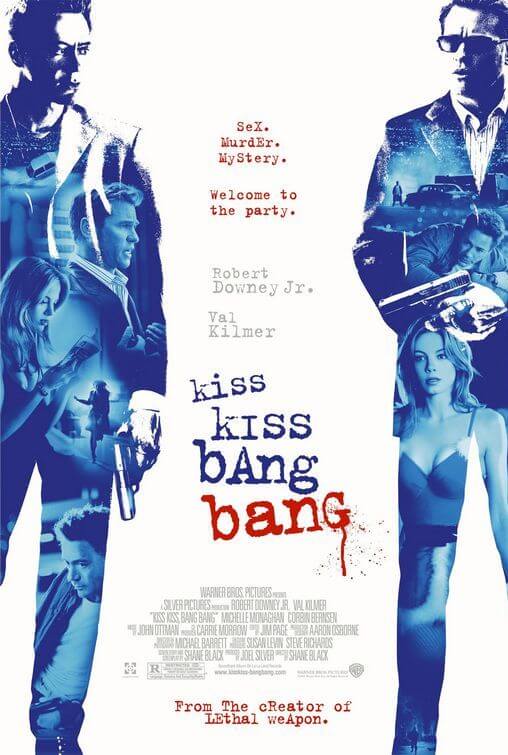

Overlooked upon its initial release and somewhat overestimated upon its rediscovery, Shane Black’s Kiss Kiss Bang Bang is best viewed once, but perhaps only once to preserve its snarky, self-awareness. The often hilarious, fourth-wall-breaking neo-noir marked the directorial debut of longtime Hollywood staple Black, and its goodwill with both audiences and its second-chance stars would later grant Black enough due respect to warrant his turns on Iron Man 3 (2013) and the similarly themed The Nice Guys (2016). Originally called “L.A.P.I.” and inspired by countless gumshoe novels, specifically one by author Brett Halliday, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang may be the sole reason Robert Downey Jr. landed his role as Marvel’s Iron Man. It was here in which the famously troubled actor demonstrated his banter-laden, motor-mouthed persona so ingrained into the world of superheroes today. But the film would mark a comeback for more than one Hollywood talent, most notable among them its writer-director.

Shane Black has been active in Hollywood since he first emerged as a screenwriter in 1986, having freshly graduated from UCLA’s drama school. His foremost script for Lethal Weapon in 1987 earned him six figures, and earned Warner Bros. much more at the box-office. He followed the hit with shared writing duties on The Monster Squad (also 1987) and Lethal Weapon 2 (1989), then The Last Boy Scout (1991), and The Long Kiss Goodnight (1996). The latter title earned a whopping $4 million payday, an unheard-of amount for a spec script at that time. But when The Long Kiss Goodnight turned out to be a major box-office bomb—much like The Last Action Hero (1993), for which he received $1 million to rewrite—Black was blamed and he all but disappeared. Worse, Black’s early days as one of the business’ highest-paid screenwriters led to a debauched party lifestyle, a level of Hollywood decadence that reflected the posh L.A. parties he often wrote about. After The Long Kiss Goodnight flopped, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences salted the wound when they denied Black’s application for entry. For the next few years, the screenwriter disappeared from the limelight.

Black’s affinity for pulp novels would influence him as both screenwriter and director. His writing projects contain a series of oft-used tropes: His are buddy movies, usually headlined by two strong-but-vulnerable tough guys—macho, save for their hilarious flaws. His buddy movie heroes are designed to play off each other, usually one straight-man countered by a comic relief character. The leads always find themselves inside a mysterious, dangerous, twisting scenario at the center of which is a dastardly crimelord, as well as a classical damsel in distress. His films also usually take place around Christmas and feature knowing, comic narration. But it’s Black’s wild sense of humor and sharp wit that set films like Lethal Weapon apart from the otherwise gratuitousness of the typical Stallone and Schwarzenegger brand of action fare of his early output.To be sure, we may never have gotten Die Hard (1988) without Black’s arrival in Hollywood.

Black’s reputation had been tarnished not just by the financial disaster of The Long Kiss Goodnight, but by his reputation for off-screen parties, which were somewhat typical of the 1980s and 1990s excesses. It was only because of the friendships he had made during his heyday that Black was able to make a comeback with Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. Producer Joel Silver, who worked with Black on Lethal Weapon and The Last Boy Scout, read his script, (loosely) based on Bodies Are Where You Find Them, one in Halliday’s series of hard-boiled novels featuring the private detective character Michael Shayne. Silver wrangled together a modest $15 million budget, as well as two down-on-their-luck actors, each just as in need of a comeback as Black. Robert Downey Jr. was fresh out of prison and recovering from a string of treatments for drug-addiction. Val Kilmer had fallen from grace after making a personal and financial disaster out of The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996).

Black’s reputation had been tarnished not just by the financial disaster of The Long Kiss Goodnight, but by his reputation for off-screen parties, which were somewhat typical of the 1980s and 1990s excesses. It was only because of the friendships he had made during his heyday that Black was able to make a comeback with Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. Producer Joel Silver, who worked with Black on Lethal Weapon and The Last Boy Scout, read his script, (loosely) based on Bodies Are Where You Find Them, one in Halliday’s series of hard-boiled novels featuring the private detective character Michael Shayne. Silver wrangled together a modest $15 million budget, as well as two down-on-their-luck actors, each just as in need of a comeback as Black. Robert Downey Jr. was fresh out of prison and recovering from a string of treatments for drug-addiction. Val Kilmer had fallen from grace after making a personal and financial disaster out of The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996).

Not surprisingly, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang wasn’t a rousing success. Audiences weren’t yet ready for Downey Jr.’s return, or Kilmer’s, and the west coast-centric material undoubtedly isolated its audience. Distributed in limited release, the film barely earned back its small budget and went mostly unnoticed by moviegoers, despite many favorable reviews (as of this review, the film holds an 85% rating on Rottentomatoes). However, some of the most-respected critics upon its release cut into the glib, effervescent quality of the film. The New York Times’ A.O. Scott wrote, “Shane Black’s film noir is a movie with no particular reason for existing,” and Variety’s then-critic Todd McCarthy said it was “perrhaps too clever for its own good”. Among the most prominent dissenters was Roger Ebert, who quoted Pauline Kael in his review. Kael once said, “Kiss kiss bang bang” epitomizes “the basic appeal of the movies.” Ebert often voiced his admiration of Kael in his reviews, and by this logic, he should have seen Black’s film as a thorough realization of Kael’s assessment. Instead, he critiqued its “mugging so shamelessly for laughs”.

Ebert refers to the self-aware narration by Harry Lockhart (Downey Jr.), a thief-turned-would-be-actor who migrates from New York to Los Angeles to receive private detective lessons from “Gay” Perry (Kilmer), a homosexual private eye. While in L.A., Harry reconnects with his adolescent crush, Harmony Faith Lane (Michelle Monaghan), and becomes wrapped up in a noirish mystery involved Harmony’s missing sister, a former actor turned crime boss (Corbin Bernsen), and an elaborate scheme involving body doubles, shootouts, a suspected suicide, and a lost finger. True of most noir stories (neo or otherwise), the details of the plot are less important than the style in which they exist—a combination of film noir structure and Harry’s smart-assed meta-humor. For example, Harry understands the weaknesses and clichés involved in noir storytelling, and he calls them out in his voiceover, even criticizing himself for his own poor storytelling: “Fuck, this is bad narrating. Like my dad telling a joke: ‘Oh, wait back up. I forgot to tell you the cowboy rode a blue horse.’ Fuck. Anyway…” Or when he’s wrapping up the story in the finale, he tells us, “Don’t worry. I saw Lord of the Rings; I’m not gonna have the movie end 20 times.”

To be sure, Downey Jr. had been playing these roles for a number of years at this point, largely supporting parts in Wonder Boys (2000) and TV’s Ally McBeal. But films like Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, A Scanner Darkly (2006), and Zodiac (2007) helped congeal Downey Jr.’s persona that later became synonymous with Tony Stark, or Guy Ritchie’s steampunk version of Sherlock Holmes. Meanwhile, Kilmer stands out as Perry, the tough P.I. who subjects Harry to countless harsh insults and sarcasm. “Any questions, hesitate to call,” he tells Harry, fed up. The film also marked a major debut for Monaghan, whose girl-next-door quality perfectly fit the damaged Midwesterner who becomes another L.A. cliché: “It’s like someone took America by the East Coast and shook it,” says Harry, “And all the normal girls managed to hang on.” Kiss Kiss Bang Bang would not be the comeback picture for Black, Downey Jr., or Kilmer—at least not yet. Jon Favreau cites the film as the reason for seeking out Downey Jr. to play Iron Man, and after taking the iconic superhero role, the actor later called upon Black to write and direct Iron Man 3—a Shane Black film through and through. Kilmer has yet to step away from direct-to-streaming fare.

To be sure, Downey Jr. had been playing these roles for a number of years at this point, largely supporting parts in Wonder Boys (2000) and TV’s Ally McBeal. But films like Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, A Scanner Darkly (2006), and Zodiac (2007) helped congeal Downey Jr.’s persona that later became synonymous with Tony Stark, or Guy Ritchie’s steampunk version of Sherlock Holmes. Meanwhile, Kilmer stands out as Perry, the tough P.I. who subjects Harry to countless harsh insults and sarcasm. “Any questions, hesitate to call,” he tells Harry, fed up. The film also marked a major debut for Monaghan, whose girl-next-door quality perfectly fit the damaged Midwesterner who becomes another L.A. cliché: “It’s like someone took America by the East Coast and shook it,” says Harry, “And all the normal girls managed to hang on.” Kiss Kiss Bang Bang would not be the comeback picture for Black, Downey Jr., or Kilmer—at least not yet. Jon Favreau cites the film as the reason for seeking out Downey Jr. to play Iron Man, and after taking the iconic superhero role, the actor later called upon Black to write and direct Iron Man 3—a Shane Black film through and through. Kilmer has yet to step away from direct-to-streaming fare.

Upon first viewing, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang is a lark, which explains its cultish popularity among videophiles in the subsequent years, mostly after Iron Man (2008). Though many of its jokes and gags on the audience aren’t as effective with home viewing, and Harry’s self-aware narration loses its shock value on a second or third screening. Consider when the film itself seems to stop between two frames while Harry analyzes his own narration in a scene—such a moment might’ve seemed hilarious in the theater when celluloid was still being projected. At home, it loses its charm. Likewise, it just doesn’t work anymore when Perry addresses the audience: “Thanks for coming, please stay for the end credits, if you’re wondering who the best boy is, it’s somebody’s nephew… Don’t forget to validate your parking, and to all you good people in the Midwest, sorry we said fuck so much.” However, Perry should have been apologizing for the film’s several remarks that further gay stereotypes and seem about fifteen years out-of-date—one of the film’s most unfortunate characteristics.

Although the novelty of a protagonist who’s aware he’s in a noir thriller grows tiresome, the comic banter between Downey Jr. and Kilmer remains priceless for much of the film, showcasing these two underrated actors (at the time) at their most affable best. The plot, too, keeps us guessing. Not that it matters. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang is as many of its detractors claimed, light and ultimately pointless. But then, so are most of the pulp novels this film emulates and directly references throughout, and even celebrates with several characters who love, and acknowledge the film’s similarities to such fiction. Black demonstrates his control over the pulp style that inspired him, and that drives his characters through an L.A. neo-noir. On the whole, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang marks an important precursor in the careers of those involved, even if what came after for these talents remains more substantial. Playful, sometimes shocking, and always fun, it’s necessary viewing for fans of Downey Jr., Kilmer, and especially Shane Black.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review