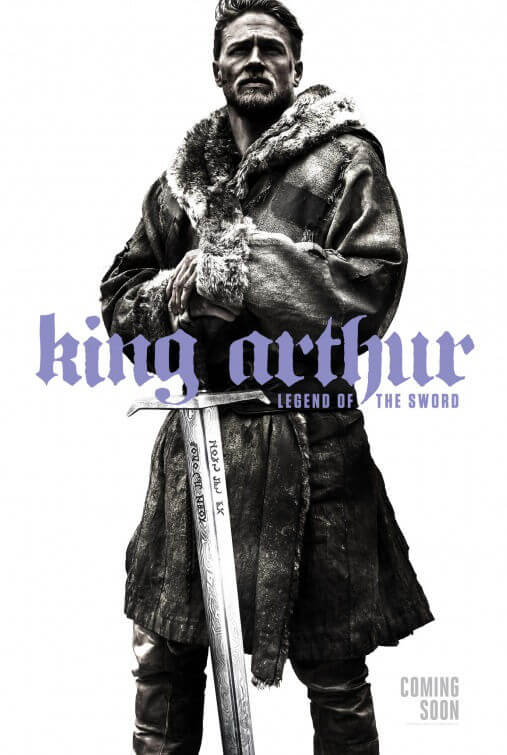

King Arthur: Legend of the Sword

By Brian Eggert |

Guy Ritchie’s King Arthur: Legend of the Sword benefits from the lack of a canonical Arthurian narrative. Texts recounting the adventures of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table have varied for more than a thousand years, but a few basic elements exist throughout. Uther Pendragon fathers Arthur, a sworn king who proves his might by extracting the magical sword Excalibur from the stone, granting him the right to rule. Guided by the wizard Merlin and with wife Guinevere at his side, Arthur vanquishes the Germanic tribes of Saxons, establishing the Anglo-Saxon empire of Great Britain. In Sir Thomas Malory’s 1485 revision Le Morte d’Arthur, the hero’s trusted knight and friend Lancelot was added to the legend, involving a betrayal with Guinevere. Cinema has done little to consecrate the legend with any regularity. Disney’s 1963 cartoon The Sword and the Stone or the musical Camelot (1967) deserve their popularity, though Antoine Fuqua’s Braveheart-esque attempt at grittiness in King Arthur (2004) is best forgotten. To this day, John Boorman’s mystical Excalibur (1981) remains the gold standard in spite of its eighties-ness. Regardless, Ritchie’s retelling has little use for most of the historical trends in Arthurian legend.

After failing to launch a franchise with the underrated 2015 flop The Man from U.N.C.L.E., Ritchie teams with Warner Bros. to make the same mistakes all over again but on a different intellectual property. Rather than just telling the story people expect to see, Richie and company demand the audience wait to see Merlin, Guinevere, or the Knights of the Round Table until a sequel that will probably never come—all in hopes of establishing a franchise and brand. Granted, a similar approach worked on Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes by holding back the titular detective’s archnemesis Moriarty until the sequel. But King Arthur: Legend of the Sword will likely become another in a long line of franchise-starters that fizzle out. Several credited writers, a long-delayed release date, and much cutting from Ritchie’s initial more-than-three-hour cut suggest a work in progress rather than a clarity of vision. And reported last-minute rewrites (carried out just two weeks after shooting started) that removed Guinevere further establish Ritchie’s narrow, tough guy’s version of the tale—there are no strong female roles here—as opposed to the romantic, sprawling epic that has worked for centuries.

Ritchie’s take feautres Arthur (Charlie Hunnam) as an orphan found on the River Thames, then raised in a Londinium brothel and forced to sharpen himself as a pickpocket and street fighter. Having repressed any memory of his late king-father’s (Eric Bana) betrayal by uncle Vortigern (Jude Law, quite good), Arthur reluctantly draws his father’s all-powerful sword from the intractable stone. Vortigern, now serving as a despised sorcerer-king, searches for his nephew with plans to kill him, thus securing his kingship. And when he sees Arthur hold Excalibur in all its glory, it means trouble. Luckily, Vortigern has aligned himself with a trifecta of slimy serpent-women that promise his ascension as long as he keeps sacrificing loved ones; in exchange, he receives magical powers (mostly fireballs). Meanwhile, Arthur remains a reluctant hero until he works through some lingering baggage, at which point he resolves to dethrone Vortigern and take his rightful seat in Camelot.

In many ways, this is a Guy Ritchie film to a fault. Blokes with names like Goose Fat Bill and Kung-Fu George stand around hatching plans, while the director’s kinetic editing cuts away to the plan in action, and then back again to the scheming. Several sequences like this, though dazzling in capers Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels or Snatch, remove the viewer from the immersive potential of the narrative. They also provide Ritchie an energetic way of zipping through footage, thus reducing the runtime to a scalable, commercially viable length, even as he sacrifices his film’s epic scope. Rather than follow Arthur as he carries out his destiny, he’s placed outside of his own story. More often than not, allies like Bedivere (Djimon Hounsou) and the Mage (Astrid Bergès-Frisbey) watch Arthur’s growth into a hero from their perspective, which puts Arthur at a distance from the audience. To be sure, Ritchie seems more interested in his own details and flourishes than supporting the narrative or allowing the viewer to accompany the hero on his journey.

Even so, King Arthur: Legend of the Sword features some profoundly un-Ritchie moments, such as a deus ex machina in the form of an unintentionally hilarious giant CGI snake. Indeed, much of the film’s final third looks and plays like a videogame, complete with Arthur going into what I will call “Excalibur-mode” when he mows down dozens of armed guards, or the final boss battle with a fireball throwing demon. Scenes in Excalibur-mode feature an Uncanny Valley version of Hunnam slicing through baddies, looking suspiciously like a cutscene out of Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor. But it’s not just the finale; from the opening battle scene in which elephants that would dwarf a brontosaurus march toward Camelot, Ritchie’s fantasy world seems over-the-top in the wrong ways. Much of the film consists of ridiculous set-pieces and flashy formal touches, none of which enhance the narrative or provide Hunnam (who recently proved his acting chops in The Lost City of Z) with much to do.

And though no viewer should enter a Ritchie film expecting traditions to be upheld, the director’s usual way of shaping a story does Arthurian legend a disservice. Hacking the film’s forward momentum into a series of short, postmodern bursts and cutaways, no matter how effective elsewhere, robs the story of its sweeping quality and prevents us from feeling like we are witnessing the birth of a legend on a grand scale. Instead, there’s dim humor, such as when Arthur’s friends spy the Round Table under construction and ask, “What is it? A carousel, a round of cheese?” Ritchie’s previous three efforts into established territory proved far more enjoyable and more evenly balanced between the period setting and their director’s electric presentation. However, cinematographer John Mathieson’s lensing in muddy earthtones, alongside composer Daniel Pemberton’s attempts to sound rustic by blending folk-sounding strings with heavy metal tempos, just doesn’t work here. It’s unfortunate, because Ritchie has a lot of talent. But don’t get your hopes up for the director returning to his roots in crime anytime soon; his next project is a live-action version of Aladdin for Disney. Another giant CGI snake, anyone?

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review