Kinds of Kindness

By Brian Eggert |

Compliance, doubles, ominous dreams, car crashes, druggings, social control, animalistic human behavior, and self-annihilation to feel loved—these themes permeate Kinds of Kindness, an anthology by Yorgos Lanthimos, the experimental Greek filmmaker whose absurdist cinema conjures both admiration and revulsion, often (and hopefully) both. Such themes extend to his other films, revealing the dichotomy between humanity’s base nature and our pretense as a civilized species, our desire for freedom despite our need for order, and, above all, the humiliating lengths we will go for love. In his breakout feature, Dogtooth (2009), Lanthimos explored parents who shelter their pet-like children from the world, establishing a distinct method of obedience. A similar family dynamic inhabits The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017), a revenge story that shows a paterfamilias’ authority over his family and career to be vulnerable and false. Lanthimos also characterizes how our need to feel loved results in self-debasement or self-destruction in The Lobster (2015) and The Favourite (2018). Kinds of Kindness revisits these ideas in a trilogy of surreal stories written by Lanthimos and his frequent collaborator Efthymis Filippou, each mining humanity’s relationship with control and desire. Likely to draw ire from the same literalists who slung moral judgments at last year’s Poor Things, Lanthimos’ latest entry in the Greek Weird Wave once again operates in the mode of fantasy and fable, crafting a triptych full of observations about human behavior in symbolic terms.

Doubtless, some moviegoers will be unable to see beyond the surfaces of these fables, which involve open sexuality, cultish devotion, animal cruelty, cannibalism, self-mutilation, and rape. In a culture intent on shielding itself from unpleasant or triggering material, a film like Kinds of Kindness will provoke strong reactions. Well, obviously. Lanthimos didn’t make it to go down easy or be watched passively. But whether moviegoers (or critics, for that matter) will recognize that they’re being prodded and respond with inquisitiveness rather than the unconsidered reflex of a knee-jerk reactionary, well, that depends on the individual. Kinds of Kindness is less commercial than Lanthimos’ last two features, though it cost $15 million, which is around his typical budget. He is, after all, an arthouse director who just so happened to draw awards attention with The Favourite and Poor Things. Regardless, Lanthimos tests the boundaries of representation to shock his audience out of their apathy and prompt questions about destructive behavior patterns at the office, in relationships, and in belief systems and social structures. Even if the stories don’t always resemble reality, their lessons are universal.

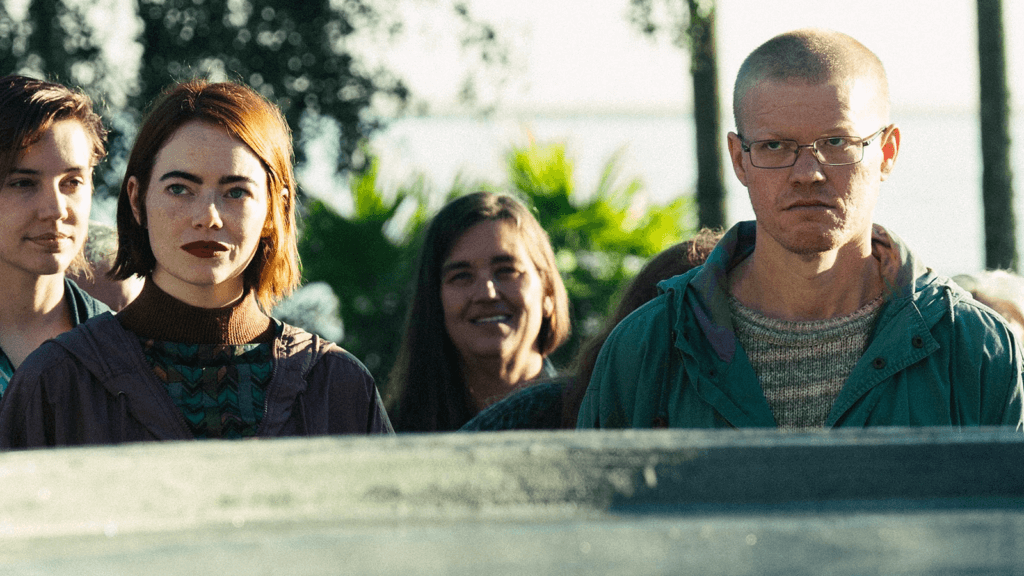

In each chapter, Lanthimos explores similar themes using the same actors, headed by Jesse Plemons (who won the Best Actor prize at the Cannes Film Festival) and Emma Stone. They’re supported by Willem Dafoe, Hong Chau, Mamoudou Athie, Margaret Qualley, and Joe Alwyn, along with some brief appearances by the director’s friend, Yorgos Stefanakos, as a recurring character named “R.M.F.” Each story takes place in a nondescript American location; the film was shot in New Orleans, but the surroundings are never recognizable. Once again teaming with cinematographer Robbie Ryan, Lanthimos makes the plain settings—office buildings, suburban homes, posh mansions, and scuzzy motels—look normal enough. They have a yellowish, bland color palette that suggests mundanity and ordinariness, albeit shot with the archness of rather Kubrickian wide angles, master shots, and symmetrical compositions that heighten the material and imbue it with figurative potential. Likewise, Jerskin Fendrix’s score alternates between abrasive, discordant piano notes reminiscent of musical motifs in Eyes Wide Shut (1999) and choral harmonies chanting what sounds like “No!” on repeat. The uncanny effect, combined with the arcane stories, lends an air of caustic intrigue.

The first tale, “The Death of R.M.F.,” introduces Robert (Plemons), a generic businessman who works an unspecified office job and lives in a cushy house with his attendant wife, Sarah (Chau). Robert is a supplicant of his godlike boss, Raymond (Dafoe), who, for years, has provided Robert with daily instructions on how to live: what to eat for breakfast, when to have sex, how much to weigh, whether or not to have children, and countless other details, no matter how minuscule or life-altering. Good behavior has earned Robert and Sarah a curious collection of sports memorabilia from Raymond, such as the latest, a “genuine smashed McEnroe” tennis racket. It has also earned Robert a sense of purpose. Raymond’s new task demands that he directs his SUV into a BMW driven by a willing participant—hard enough to land Robert in the hospital and kill the other driver. But after so many sacrifices, Robert questions the gravity of his latest order, inciting Raymond to cut him loose. Robert quickly discovers that he’s aimless without Raymond’s instructions and the pleasure he receives from fulfilling them, and he tries desperately to reestablish their dom-sub relationship, which, to no one’s surprise, has a sexual dimension as well.

The first tale, “The Death of R.M.F.,” introduces Robert (Plemons), a generic businessman who works an unspecified office job and lives in a cushy house with his attendant wife, Sarah (Chau). Robert is a supplicant of his godlike boss, Raymond (Dafoe), who, for years, has provided Robert with daily instructions on how to live: what to eat for breakfast, when to have sex, how much to weigh, whether or not to have children, and countless other details, no matter how minuscule or life-altering. Good behavior has earned Robert and Sarah a curious collection of sports memorabilia from Raymond, such as the latest, a “genuine smashed McEnroe” tennis racket. It has also earned Robert a sense of purpose. Raymond’s new task demands that he directs his SUV into a BMW driven by a willing participant—hard enough to land Robert in the hospital and kill the other driver. But after so many sacrifices, Robert questions the gravity of his latest order, inciting Raymond to cut him loose. Robert quickly discovers that he’s aimless without Raymond’s instructions and the pleasure he receives from fulfilling them, and he tries desperately to reestablish their dom-sub relationship, which, to no one’s surprise, has a sexual dimension as well.

Part of watching the first segment and those afterward involves getting a handle on the strange little worlds these characters inhabit. Though, “R.M.F. is Flying” is the second and most (relatively) straightforward of the bunch. Plemons plays Daniel, a cop whose wife Liz (Stone) disappeared at sea some time ago. When she’s found and returns from her desert island, Daniel is convinced she’s not the person he married. She looks the same, but details have changed: her feet have grown; she now likes chocolate, though she never used to; and she doesn’t remember Daniel’s favorite song. Their close friends and group sex partners (Athie, Qualley) don’t notice that anything is off, so Daniel proceeds to test her, even as he unravels in an apparent mental breakdown. Whether or not she’s a doppelgänger is almost less interesting than her claim that dogs ran the island where she was stranded, and scenes over the end credits of this episode offer a few inspired visual gags to consider a world run by dogs—the funniest of which, disturbingly so, involves a dead child in the street, discarded like a roadkill pet on the highway.

The final installment, “R.M.F. Eats a Sandwich,” finds Emily and Andrew (Stone, Plemons) looking for a twin prophesied to bring the dead back to life. They belong to a cult operated by Omi and Aka (Dafoe, Chau)—New Age gurus with distinct notions of purity, who subject their followers to sexual contamination checks and limit their water intake to a pool spiked with their tears. Emily, who drives a purple Dodge Challenger at top speeds wherever she goes, has left her husband (Joe Alwyn) and daughter to commit herself to the cult. But those family ties inevitably lead to a break with her benefactors, even as she narrows the search for the Chosen One down to a likely candidate (Qualley). Ending on a particularly bleak note, Kinds of Kindness may not strike the viewer with the same gut punch as the director’s other work, perhaps because of the fractional-feeling anthology structure. This is by design, of course; ultimately, it’s an inescapable reality of any anthology picture, regardless of the excellent cast and thematic ties between the stories. Stefanakos’ presence in each as R.M.F. hardly links the three segments, making each tale a variation on closely aligned themes.

What’s refreshing is that Kinds of Kindness avoids spelling out its purpose. However, its title underlines the meaning well enough, marked by stories in which people perform desperate acts in exchange for perceived love or grant love only after registering compliance with their exploitative terms. The film questions the absurd lengths to which people will go to feel acknowledged, embraced, or loved, and it achieves this with a sublime variety of bizarre, funny, shocking, and witty stories. Running nearly three hours, Lanthimos’ latest may be a challenge for some given its subject matter, or worse, supply an anathema for an increasingly prudish and conservative culture that seems determined to stifle unconventional expressions—particularly those involving sexuality or nudity, even displays not intended to be sexy, in art—and then label their presence as purposeless or dangerous. It’s a worrying trend that finds commentators unable to distinguish between representation and endorsement, content and meaning, and it thoughtlessly feeds increased calls for censorship. Pushing boundaries is essential to artistic growth, and Lanthimos and his cast are admirably and unabashedly uninterested in curbing their creative freedoms, trusting, perhaps misguidedly so, that their audience will grow with them on their outlandish, irrational, but also relatable journey.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review