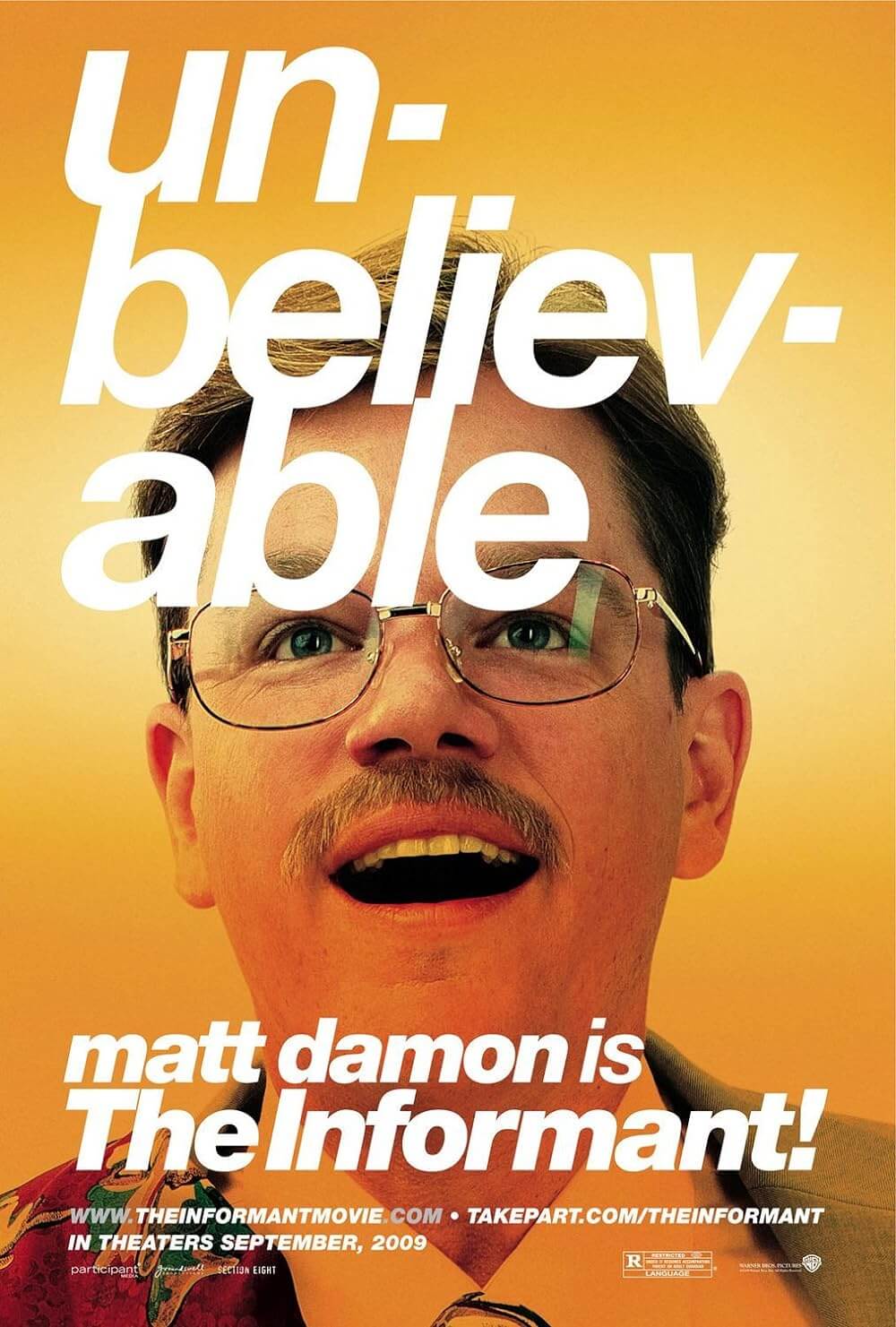

KIMI

By Brian Eggert |

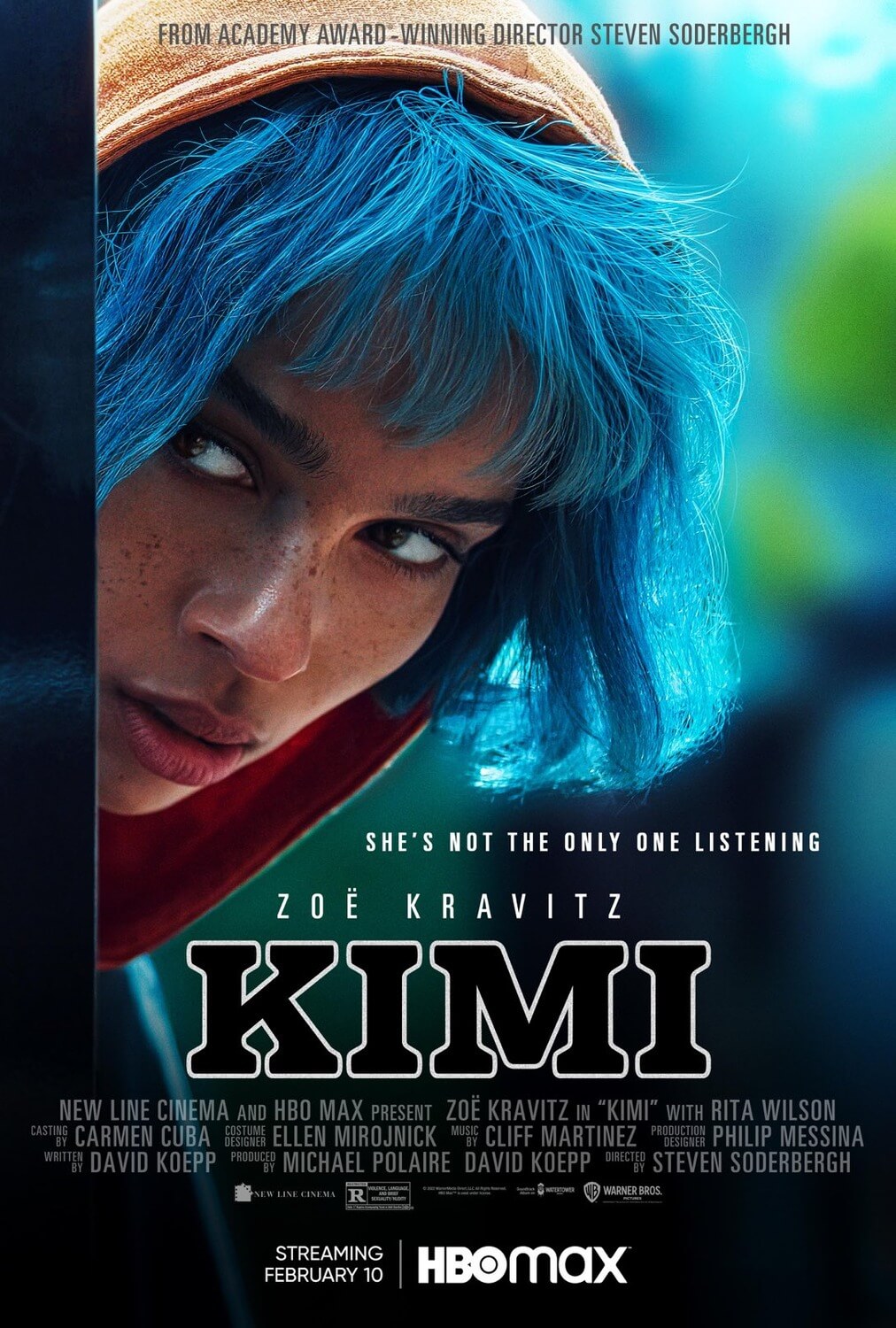

Steven Soderbergh’s career has become a series of genre exercises. Working with Netflix and HBOMax in recent years, Soderbergh—serving as director, as well as cinematographer and editor under his usual pseudonyms—has delivered what feel like hand-crafted films that explore well-worn territory. With his sports agent drama, High Flying Bird (2019), and last year’s No Sudden Move, about a heist-turned-corporate-coverup, the admirably independent filmmaker elevated excellent scripts by applying sharp visuals and wry tonality. Maybe that’s what he’s always done. After all, before he started working with streamers, he had been making programmers such as the pharmaceutical conspiracy yarn Side Effects (2013), the race car robbery movie Logan Lucky (2017), and the trapped-in-an-asylum thriller Unsane (2018). So his latest for HBOMax, KIMI, feels right in line with his output lately. It’s a familiar story, to be sure, but Soderbergh’s treatment reminds us why he’s one of the most reliable filmmakers out there.

KIMI was written by David Koepp, who also produced. Koepp has contributed to some major Hollywood screenplays over his 35-year career, including Jurassic Park (1993), Spider-Man (2002), and War of the Worlds (2005). But he always returns to the realm of small-scale thrillers such as Trigger Effect (1996) and Premium Rush (2012) in-between his larger studio projects. Just like Soderbergh, he is a dependable source of genre work and frequently excels within those limitations. KIMI finds these two masters of genre joining forces for something that’s part Hitchcock, part conspiracy thriller. It borrows familiar elements of voyeurism from Rear Window (1954) and combines them with the paranoia and omnipresent recording of The Conversation (1974) and Blow Out (1981), and it reinvigorates these ideas. In other hands, these hard materials of story and genre would have proven inadequate, but in Soderbergh and Koepp’s capable hands, they build a sturdy structure.

Giving her finest screen performance outside of her two seasons on Big Little Lies, Zoë Kravitz plays Angela Childs, a Seattle-based agoraphobic who works for a tech corporation called Amygdala. They make KIMI, the next version of Alexa or Siri, the virtual assistants that consumers invite into their homes to listen and await questions or orders. Working from home, Angela clears error reports created from flagged miscommunications. So, for instance, if KIMI doesn’t understand when someone uses regional slang when ordering a roll of “kitchen paper,” Angela will receive a report and teach the AI that such requests mean “paper towels.” Of course, this also means KIMI records everything everyone says to become a better virtual assistant. And when Angela discovers an audio recording of a rape, and after some digging, further evidence of a murder, she takes it upon herself to investigate.

KIMI is also set during the current pandemic, in the world of virtual meetings and face coverings. There have been a handful of COVID-19 movies made in the last two years, and outside of Host (2020), about a haunted virtual meeting, none are worth mentioning. KIMI is an exception because it uses COVID-19 to add dimension to our hero. Angela’s agoraphobia stems from a sexual assault a few years before, and pandemic isolation has only accentuated her existing anxieties about going outside. Small details about the character, along with Kravitz’s convincing performance, create a believable character pushed to her limit by isolation—evidenced by her small pharmacy of medications, a nighttime mouthguard to protect her teeth and jaw from nocturnal grinding, persistent use of hand sanitizer, and unwillingness to leave her apartment to meet her neighbor (Byron Bowers) for a hookup. For a certain type of viewer, all of this anxiety-ridden behavior will be all too relatable. What’s more, the setup shares DNA with thrillers about isolated women like the abysmal The Woman in the Window (2021), where the unreliable protagonist makes claims she might not be able to prove. However, Angela’s conspiracy theory isn’t a symptom of her hangups.

KIMI is also set during the current pandemic, in the world of virtual meetings and face coverings. There have been a handful of COVID-19 movies made in the last two years, and outside of Host (2020), about a haunted virtual meeting, none are worth mentioning. KIMI is an exception because it uses COVID-19 to add dimension to our hero. Angela’s agoraphobia stems from a sexual assault a few years before, and pandemic isolation has only accentuated her existing anxieties about going outside. Small details about the character, along with Kravitz’s convincing performance, create a believable character pushed to her limit by isolation—evidenced by her small pharmacy of medications, a nighttime mouthguard to protect her teeth and jaw from nocturnal grinding, persistent use of hand sanitizer, and unwillingness to leave her apartment to meet her neighbor (Byron Bowers) for a hookup. For a certain type of viewer, all of this anxiety-ridden behavior will be all too relatable. What’s more, the setup shares DNA with thrillers about isolated women like the abysmal The Woman in the Window (2021), where the unreliable protagonist makes claims she might not be able to prove. However, Angela’s conspiracy theory isn’t a symptom of her hangups.

Inevitably, Koepp’s script forces Angela to leave her apartment. Amygdala wants to hear the recording of the murder, and leaving the house means a sensory overload for Angela—leaving the smoothly photographed comfort zone of Angela’s living space and entering the chaotic outside. Soderbergh captures this with a wave of sound and off-kilter camerawork that conveys the disorienting effect of overwhelming anxiety and sensory stimuli. KIMI is particularly effective for its sound design. Not only does Cliff Martinez’s terrific score set the tone, but Larry Blake’s sound infuses an omnipresent sense of ambient noise and pointed breaks in the soundscape. We notice the din of construction in the upstairs apartment or the general background noise outside and when it’s broken by diegetic music or Angela’s review of KIMI recordings. When she finally sets out to visit Amygdala, the score, camera angles, and audio environment burst into disorder.

Soderbergh’s casting adds another layer to KIMI of alternating humor and dread. Matters only become worse for Angela after realizing she heard something she wasn’t supposed to. Her company wants to cover it up, so Soderbergh casts the pleasant Rita Wilson as a quality control manager with nothing but false empathy and flattery to handle Angela. It’s a chilling use of casting to make the situation feel turned upside down. And then there’s the guy across the street from Angela’s apartment who watches her with binoculars, played by Devin Ratray—best known as Buzz from Home Alone (1991), and here named Kevin no less. Other Soderbergh collaborators make appearances too, such as Erika Christensen (Traffic, 2000) playing the resident murder victim and Betsy Brantley (Schizopolis, 1996), Soderbergh’s ex-wife, voicing KIMI.

The last third of KIMI includes a tense chase and confrontation that make clever use of confined spaces, recalling the Koepp-scripted Panic Room (2000), complete with a breathless home invasion sequence. The film also boasts a healthy suspicion of corporate power and technology—and the associated information gathering, data mining, and tracking by the devices everyone carries in their pockets. Of course, Koepp’s screenplay ultimately allows Kravitz’s character to resolve the conflict, and in doing so, overcome the worst of her anxieties and past trauma, thus following the prescribed narrative trajectory for this type of scenario. But Soderbergh handles everything with an expert eye, portraying each familiar beat with an inventive camera angle or movement that enriches everything onscreen (the final shots, especially, are a pleasure to behold). The writing, performances, and overall aesthetic combine into a form-follows-function presentation, which delivers in every way that it should. It’s a perfectly satisfying thriller, which is a rare and beautiful thing.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review