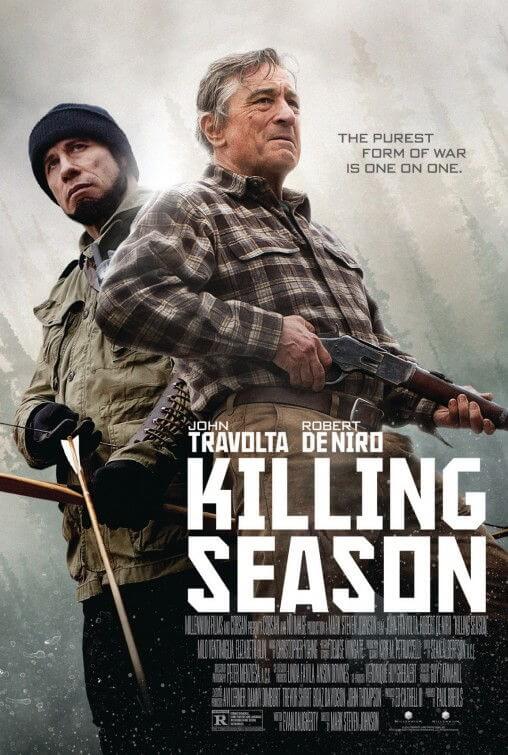

Killing Season

By Brian Eggert |

Take yourself back to 1997 for a moment. Then still riding his post-Pulp Fiction resurgence, John Travolta had just released a string of commercial and critical successes, including Get Shorty and Face/Off. Meanwhile, just two years earlier, Robert De Niro had reminded moviegoers why he’s a living legend in Michael Mann’s Heat, whereas Wag the Dog and Jackie Brown reinforced this notion even further. Neither actor had yet soiled their reputations with drivel like From Paris with Love, Righteous Kill, or the dozen other flops that would follow in the next decade or more. At their height in ‘97, a film like Killing Season would have been highly anticipated just because it marks the first onscreen pairing of these two. But today, it’s another in a long line of obscure curiosities from once-reliable performers.

Snow White and the Huntsman scribe Evan Daugherty wrote Killing Season, which made the 2008 “Black List” of Hollywood’s best yet-unproduced scripts. Daugherty’s original story took place in the 1970s and followed an American World War II veteran who’s confronted by a Nazi he met during the war. At the time, John McTiernan (Die Hard and Predator) was in talks to direct. Sounds promising, no? But the eventual production, distributed by Millennium Entertainment, was directed by Mark Steven Johnson of Daredevil and Ghost Rider infamy. Johnson’s version has a modern-day setting and, instead of the ever-iconic WWII, uses the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s for a dramatic backstory. The result is not only ineffective but becomes a dramatically inert, overly violent embarrassment for both De Niro and Travolta.

De Niro plays Benjamin Ford, a former U.S. colonel. Travolta plays Emil Kovac, who served under the notorious Serbian Scorpions during the conflict. In a brief prologue that barely taps into the genocide that occurred in Bosnia, we see NATO soldiers execute cruel war criminals on the spot. For years, Kovac has waited to confront Ford, a member of the firing squad who, at point blank range, somehow didn’t hit his target. Trekking out to Ford’s rustic cabin retreat somewhere in the Appalachians, the garrulous Kovac arranges a seemingly random run-in with Ford. Endless chitchat ensues, and we suspect they might actually have made good friends. They both enjoy Johnny Cash and Jägermeister—what else is there to friendship? But this is just a rouse until Kovac can get his mark out into the woods, alone. Once there, he engages Ford in a game of cat-and-mouse with a bow and arrow. More deadly is the endless, cliché banter exchanged on walkie-talkies.

Within minutes, a thriller born from John Boorman’s Hell in the Pacific and William Friedkin’s The Hunted devolves into something far too closely resembling torture porn, a staggering incongruity next to the film’s would-be philosophical message about redemption and forgiveness. When they start in on each other, it gets unbearable: Kovac forces Ford to thread a steel rod through an arrow wound in his leg and then hangs Ford upside down; Ford shoots an arrow through Kovac’s cheeks, and then makes him drink salt-infused lemon juice. Waterboarding, stabbings, gunshots, and other violent acts muddle any hope for the film’s intended themes. Forget political awareness or social commentary, or even human understanding; the film is content to sell you big-name stars doing horrible things to one another. On the plus, Johnson’s cinematographer Peter Menzies Jr. captures some gorgeous autumnal scenery in locations around Tallulah Falls, Georgia (where Deliverance was shot). But no amount of momentary beauty can make up for this ugly, mean-spirited storytelling.

And what about those stars? De Niro’s inconsistent southern accent is nothing compared to the overwrought Eastern European brogue uttered by Travolta, who seems to be auditioning for a role as Count Dracula. Worse than Travolta’s goofy accent are his tight-trimmed hair and chinstrap beard, both dyed jet-black with liberal uses of Just For Men. Painted onto Travolta’s noggin, perhaps to disguise the actor’s thinning hair, the black coloring glistens in some scenes, suggesting the hair and makeup department spent a lot of time and a pretty penny slathering shoe polish onto Travolta’s head. At any rate, both actors seem off their game, each lazily and inconsistently speaking in their respective accents. It forces one to ponder if De Niro and Travolta signed-on back when this was a compelling tale about an American and a Nazi, and Tiernan were involved, or if they agreed to star after Johnson and Daugherty turned this into a gristly hunk of torture porn. It’s difficult to imagine either actor agreeing to a project like this fifteen years ago.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review