Killers of the Flower Moon

By Brian Eggert |

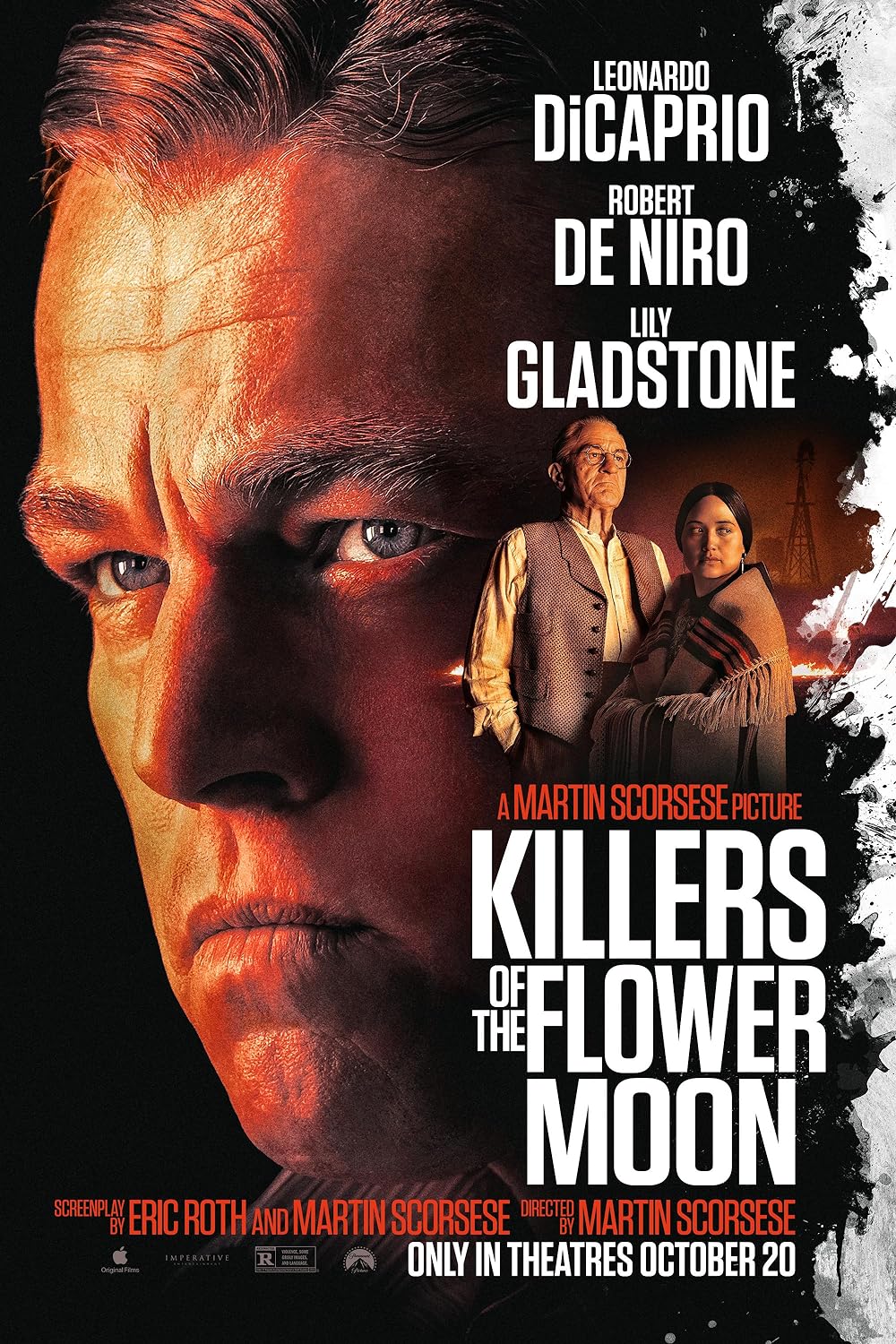

A sprawling and thoughtful epic, Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon details a horrific and mostly overlooked chapter of American history. Marked by greed and murder, the story, at its most basic level, is about the evil that men do. Based on the best-selling nonfiction book by David Grann—published in 2017 under the title Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI—the film details how ruthless white men conspired to steal wealth from the Osage Nation, whom they deemed unworthy of such riches, to the extent that they systematically murdered them to obtain it. Although the story is a microcosmic account of the crimes against Native Americans in the name of Manifest Destiny, money, land, and white superiority, Scorsese’s film commits a forgotten history to a visual and thematic panorama—a cinematic memory that no one will soon forget. Teaming for the first time in a single film with his two most frequent collaborators, Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio, Scorsese’s three-and-a-half-hour film probes into not just the investigation that uncovered the conspiracy but also the curious case of pathological compartmentalization that fuelled the actions of its perpetrators. In both form and narrative power, Killers of the Flower Moon is a bold, albeit meditative step for the 80-year-old filmmaker, who’s still taking risks and evolving with each subsequent film.

Grann’s book outlines how, in the 1890s, one of the largest oil deposits in the United States was discovered on Osage land. The Osage people retained the headrights to the oil fields, requiring prospectors to pay for licenses to drill. Within a short period, the Osage Nation became unthinkably wealthy, and within 20 years, they were among the richest people in the world. However, the oil would soon be a “cursed blessing” among the Osage people. White opportunists lobbied until Congress passed a law requiring a court-appointed guardian to manage the financials of any Osage person of half-blood or more in ancestry, determining that only a person with a majority of white blood could ensure fiscal “competency.” These guardians often stole from and upcharged their wards for basic goods and services. Other white men married their way into Osage families, and should their family members disappear or meet an untimely demise, the white men who had weaseled their way into the community would inherit the wealth. What followed was a systematic elimination of people who stood between these unscrupulous guardians and Osage fortunes—crimes that, for many years, went unpunished. After all, the saying around Osage County at the time was that it’s “easier to kill an Indian than a dog.” Monstrously calculated and executed, the deaths occurred in Oklahoma between 1918 and 1931, resulting in 60 members of the Osage Nation confirmed murdered, and likely many more.

The screenplay by Eric Roth (Munich, 2005) and Scorsese deviates from the structure of Grann’s book, which assesses the crimes with an investigator’s eye for details and loose ends. Grann spent ten years researching the murders, and his account weaves the facts into a major case for the young Federal Bureau of Investigation, with Agent Tom White pursuing every lead. While the original case exposed several responsible parties, including the mastermind orchestrating the scheme, Grann’s research uncovered the likelihood of more deaths. But too much time has passed to attribute every victim or name every culprit with any certainty. All one can do is speculate about the disturbing scope of the crimes beyond what is known. Initially, the screen story centered on the investigation, with DiCaprio playing White. But Scorsese soon realized that to tell this story truthfully and acknowledge the open wound of the Osage Nation, he and Roth had to approach the genocide from within, focused on the complex relationship between Ernest Burkhart (DiCaprio) and his Osage bride, Mollie (Lily Gladstone). Only from the inside can the viewer grasp the hideous level of betrayal at work—and the mental gymnastics that allow people to kill their professed loved ones, friends, and neighbors if it means a sizable payday.

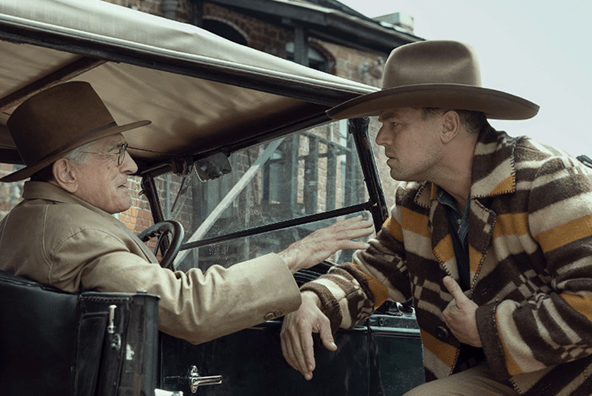

When Earnest returns from the First World War to Fairfax, Oklahoma, his uncle, the seemingly benevolent William Hale (De Niro), who likes to be called “King,” is already scheming to secure oil headrights. Hale slyly encourages Ernest to seek an Osage bride to do the same. When Ernest first meets Mollie, serving as her cab driver, it’s not under any pretense that he flirts with her. She’s pretty and has a mysterious way of speaking with her intelligent eyes. Under Hale’s advisement—because Mollie is a “smart investment”—Ernest learns the Osage culture and language. He begins courting her, remarking on her beauty and complimenting her skin color; she gives him a Stetson hat and invites him over for dinner. They both enjoy drinking and creature comforts. And though Mollie’s sisters warn that Ernest is a snake, like many other white men they know, she defends that Ernest merely wants to be “settled.” For his part, Ernest flat-out tells Mollie, “I love money,” and his ambition is to “sleep all day and party all night.” His hunger for money is unmistakable, yet the love between Mollie and Ernest is some kind of genuine. They are soon married. At the same time, Ernest performs jobs for Hale, such as robbing Osage people of jewelry at gunpoint or hiring some shady characters to carry out a murder.

When Earnest returns from the First World War to Fairfax, Oklahoma, his uncle, the seemingly benevolent William Hale (De Niro), who likes to be called “King,” is already scheming to secure oil headrights. Hale slyly encourages Ernest to seek an Osage bride to do the same. When Ernest first meets Mollie, serving as her cab driver, it’s not under any pretense that he flirts with her. She’s pretty and has a mysterious way of speaking with her intelligent eyes. Under Hale’s advisement—because Mollie is a “smart investment”—Ernest learns the Osage culture and language. He begins courting her, remarking on her beauty and complimenting her skin color; she gives him a Stetson hat and invites him over for dinner. They both enjoy drinking and creature comforts. And though Mollie’s sisters warn that Ernest is a snake, like many other white men they know, she defends that Ernest merely wants to be “settled.” For his part, Ernest flat-out tells Mollie, “I love money,” and his ambition is to “sleep all day and party all night.” His hunger for money is unmistakable, yet the love between Mollie and Ernest is some kind of genuine. They are soon married. At the same time, Ernest performs jobs for Hale, such as robbing Osage people of jewelry at gunpoint or hiring some shady characters to carry out a murder.

In this, Killers of the Flower Moon plays like a natural continuation of Scorsese’s career-long theme of critiquing violent and corruptive social structures, from the petty thug hierarchy in Mean Streets (1973) to the hardened mobsters in Goodfellas (1990) and Casino (1995), from the stifling metaphorical violence of social decorum in The Age of Innocence (1993) to the scheming Wall Street scammers in The Wolf of Wall Street (2013). American history is filled with organized crime, whether it’s exploiting the stock market or dehumanizing indigenous people by encroaching on their land, slaughtering their populations, making half-hearted amends, and breaking deals over the centuries. What’s unique, perhaps even controversial, about Scorsese’s approach is how he immerses the viewer within these systems, leading to misreadings that he approves of the behavior he represents onscreen. But Scorsese’s respect for the viewer asks for critical thought. And while it’s easy to see why Henry Hill savors the freedom and power of being a wise guy or why Jordan Belfort enjoyed his crudely indulgent lifestyle, Killers of the Flower Moon presents a different case, where the viewer remains at odds with Ernest, never fully empathizing with the character and creating a critical distance from the unfolding drama.

The film alternates between Mollie’s role as a grief-stricken spectator of the crimes committed against her people, including her mother and sisters, and Ernest’s role in Hale’s plan to dispose of the Osage people and obtain their headrights. Stricken with diabetes, Mollie must also take newfangled insulin shots, administered by Ernest. But they only seem to make things worse, leaving her bedridden from the poison Hale has arranged to be in each injection. All she can do is watch her loved ones disappear around her, just as powerless as the Osage Nation leaders, once warriors who would proudly fight a head-on battle, except their enemy works in the shadows. The film portrays these crimes in both silent complicity and execution-style murders and explosions, drawing comparisons to the Tulsa Race Massacre and evoking the Ku Klux Klan more than once. Against such bloodshed and treachery, Ernest registers as a weak, easily manipulated man who never questions his uncle or his orders. He doesn’t think far enough ahead to reconcile how his deeds for Hale contaminate what he perceives to be a genuine romance with Mollie. Ernest recalls De Niro’s apathetic and dutiful hitman in Scorsese’s last film, The Irishman (2019), who places his family second to his criminal obligations, only to regret his choices long after it’s too late.

DiCaprio’s complex performance is central in Killers of the Flower Moon, playing a man incapable of seeing what he’s done, who siloes the two sides of his identity—the sensitive husband and the complicit killer. It’s not until a late-film encounter with Mollie in a courthouse that the character looks inward. DiCaprio’s confused expression brilliantly shows how Ernest has never considered his betrayal or the extent of his actions. De Niro, sounding an awful lot like his Max Cady from Scorsese’s Cape Fear (1991), thoughtfully alternates between Hale’s almighty benefactor routine and his manipulative evil. The actor lends an almost comic insidiousness to simple lines, such as when the arrested Hale claims to be “more innocent than a newborn” or speaks to Ernest in front of Mollie: “I think we should be more considerate about how we spend Mollie’s money.” Gladstone, who grew up on the Blackfeet Nation reservation in Montana, has a more challenging, internalized role. There are humiliating scenes where Mollie regularly meets with her guardian, identifies herself as an “incompetent,” and requests that her money be dispensed—a request often met with refusals. Although much of her performance requires composed body language and reserved eyes, her outpourings later cry out for recognition of Gladstone’s range.

DiCaprio’s complex performance is central in Killers of the Flower Moon, playing a man incapable of seeing what he’s done, who siloes the two sides of his identity—the sensitive husband and the complicit killer. It’s not until a late-film encounter with Mollie in a courthouse that the character looks inward. DiCaprio’s confused expression brilliantly shows how Ernest has never considered his betrayal or the extent of his actions. De Niro, sounding an awful lot like his Max Cady from Scorsese’s Cape Fear (1991), thoughtfully alternates between Hale’s almighty benefactor routine and his manipulative evil. The actor lends an almost comic insidiousness to simple lines, such as when the arrested Hale claims to be “more innocent than a newborn” or speaks to Ernest in front of Mollie: “I think we should be more considerate about how we spend Mollie’s money.” Gladstone, who grew up on the Blackfeet Nation reservation in Montana, has a more challenging, internalized role. There are humiliating scenes where Mollie regularly meets with her guardian, identifies herself as an “incompetent,” and requests that her money be dispensed—a request often met with refusals. Although much of her performance requires composed body language and reserved eyes, her outpourings later cry out for recognition of Gladstone’s range.

Whereas The Irishman found Scorsese in reflection mode, with a story that looks back yet pushes the medium forward, Killers of the Flower Moon tests the filmmaker’s limits. Like The Irishman and its Netflix backers, Scorsese’s new film is another massively budgeted project funded by a streamer—the production cost a reported $200 million, with Apple Original Films writing the check. Working with many of his longtime collaborators, he explores a Western setting, having never dealt with an American West landscape or idyllic surroundings in quite this way. The material requires him to find a new visual grammar, which is far different from the crackling energy he is sometimes associated with. With Rodrigo Prieto (Scorsese’s cinematographer for the last decade) behind the camera, the production shot on location on the Osage reservation in Oklahoma, capturing scopic prairies and ocean-like fields with stunning beauty. The film’s pacing is measured and intentional, resisting the rapid-fire momentum of the director’s many collaborations with editor Thelma Schoonmaker. Including his latest, Scorsese’s last three pictures have been rather patient and classically made, but never more so than here. The late Robbie Robertson’s score accents this—a simple, single-string bass beat and a droning accompaniment of bluesy harmonica and guitar, establishing the mood of relentless dread, especially during seemingly pleasant scenes where duplicity abounds.

At every stage in the production, the filmmakers ensured authenticity for the Osage people—how their characters, language, and traditions would appear onscreen—by conferring with Osage tribe leaders and relying on consultants who helped guide the production. Actual Osage people appear in front of and work behind the camera. Gladstone, DiCaprio, and De Niro even learned the Osage language for their roles. Fortunately, Scorsese never treats the indigenous people with the clichés often employed by Hollywood productions, avoiding hagiography and negative stereotypes. Instead, his film inhabits the mindset of the Osage people, so when a character sees an omen in the form of an owl, there is no irony or mysticism, just a full embrace of a spiritual belief system. Scorsese also mourns that way of life in the creative first and last sequences. The first images find Osage elders in a funeral ritual, lamenting the “new ways” of white men that will soon dilute their traditions. With money and technology introduced to the Osage culture, they embrace their new riches—seen in silent-era newsreel footage calling the Osage Nation, “The chosen people of chance.” Rather than a typical postscript, Scorsese imagines a silent radio program recorded live on stage, in an imaginative solution to what usually involves white letters on a black screen.

But Killers of the Flower Moon isn’t the first film to confront the Osage murders. Almost a century ago, Hollywood’s first prominent Native American director, the prolific James Young Deer, tackled the Osage murders in his lost film, Tragedies of the Osage Hills. Released on May 11, 1926, the film debuted at the American Theatre in Cushing, Oklahoma, just a county over from Osage, a few short months after the arrests of Hale and Burkhart. According to The Hollywood Reporter, the production ran about 80 minutes and employed hundreds of Native American actors. Made independently by Deer and his partner Frank L. Thompson, under the local Thompson Moving Picture Corporation, the film couldn’t possibly depict the full extent of the actual crimes, which hadn’t yet been fully attributed. But the film supposedly ended with a note of optimism that seems cruelly ironic today—a shot of peace and friendship between Native Americans and whites, the American flag flying overhead. A few months later, Deer and Thompson entered a legal dispute over the prints of the film, and all prints were lost to time. After a scandal, Deer’s career wavered, and he died in relative obscurity. Ironically, promotional material from the time in the Sulphur Times-Democrat proclaims Deer’s film, “A Picture You Will Never Forget.”

But Killers of the Flower Moon isn’t the first film to confront the Osage murders. Almost a century ago, Hollywood’s first prominent Native American director, the prolific James Young Deer, tackled the Osage murders in his lost film, Tragedies of the Osage Hills. Released on May 11, 1926, the film debuted at the American Theatre in Cushing, Oklahoma, just a county over from Osage, a few short months after the arrests of Hale and Burkhart. According to The Hollywood Reporter, the production ran about 80 minutes and employed hundreds of Native American actors. Made independently by Deer and his partner Frank L. Thompson, under the local Thompson Moving Picture Corporation, the film couldn’t possibly depict the full extent of the actual crimes, which hadn’t yet been fully attributed. But the film supposedly ended with a note of optimism that seems cruelly ironic today—a shot of peace and friendship between Native Americans and whites, the American flag flying overhead. A few months later, Deer and Thompson entered a legal dispute over the prints of the film, and all prints were lost to time. After a scandal, Deer’s career wavered, and he died in relative obscurity. Ironically, promotional material from the time in the Sulphur Times-Democrat proclaims Deer’s film, “A Picture You Will Never Forget.”

At one point, Hale observes about his crimes that “people don’t care about this story.” If most people had forgotten what happened to the Osage people by the close of the twentieth century, then Grann’s book and Scorsese’s film serve a higher purpose of returning the spotlight to an unthinkable tragedy and barbaric display of predatory behavior. Killers of the Flower Moon is a vital piece of filmmaking that questions the extent people will exploit others for personal gain, and not only that, but also rationalize and separate those actions from their moral standards and personal accountability. Throughout the film, the Osage describe white men as various animals. They are buzzards who fly around, picking at the leftovers who are dead; snakes, who slither their way into Osage lives, waiting to strike; wolves, working in a pack to pick off weak prey. While animalistic metaphors may seem appropriate, there’s something uniquely human about how people will target one another based on race or culture, manipulate them, and then bleed them dry. This is the sobering, confounding reality at the heart of Scorsese’s brilliant film.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review