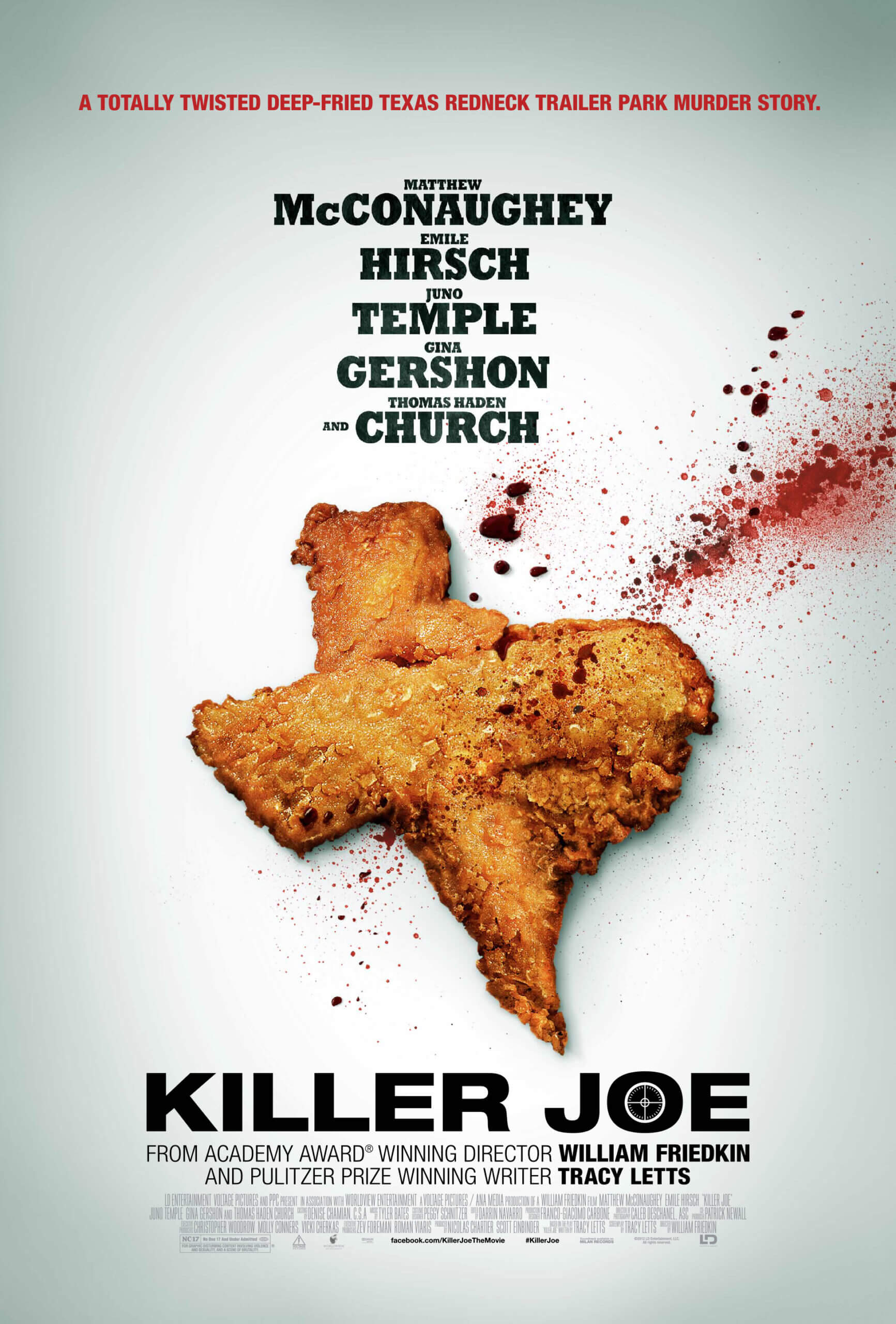

Killer Joe

By Brian Eggert |

In Killer Joe, director William Friedkin reaches magnificent new lows as he descends into playwright Tracy Letts’ world of southern-fried depravity, stupidity, sexuality, and possibly (almost certainly) madness. Although renowned and perhaps overshadowed by his early-career classics The French Connection and The Exorcist, as of late, the director has found a fruitful union with Letts’ often lurid material, having worked together on 2007’s fascinating Bug. Here, their partnership has earned an NC-17 rating, a ruinous signifier of hopeless commercial aims and limited theatrical distribution, which means most moviegoers will probably discover the title on home video. But the rating is sometimes also a badge of artistic integrity, since both the filmmakers and distributors felt changing their exploitative little “trailer park noir” to meet the requirements of a lesser R-rating would compromise its effectiveness. To be sure, every outrageous morsel of degeneracy sizzles on the screen without reservation and feels strangely appropriate in this Southern Gothic nightmare.

A morbid combination of Double Indemnity, Tennessee Williams, and the basest episode ever of The Jerry Springer Show, Letts’ twisted tale opens in a Texas trailer park just outside Dallas, Texas. Chris Smith (Emile Hirsch) arrives in the rain in the middle of the night, a chained Pit Bull named “T-Bone” barking at him as he raps on a trailer door to ask his father, Ansel (Thomas Haden Church), for $6,000 to help him pay off a local gangster for an overdue drug debt. After Ansel’s new wife Sharla (Gina Gershon) answers the door bottomless (because how was she supposed to know who was knocking?) Ansel tells Chris he doesn’t have the money. No matter, Chris sells Ansel on a plan to kill his own mother, Ansel’s ex, whose $50,000 life insurance policy will supposedly go to Chris’ virginal but wholly corrupted sister, Dottie (Juno Temple). And to get away with this perfect crime, they’ll hire Killer Joe (Matthew McConaughey), a Dallas detective who moonlights as a contract killer.

Trouble is, Joe’s fee is $25,000 upfront. The other half is to be split four ways among Chris, Ansel, Sharla, and Dottie, the latter of whom the rest are trying to keep in the dark about their scheme, although she seems to understand exactly what they’re doing. After spying on Dottie in her braless innocence, Joe suggests the family turn her over as a retainer until his murderous deed pays off. Without much hesitation, they agree. Ansel even thinks “it might do her some good.” Chris expresses mild reluctance, but that might be his unconscious incestuous feelings for his sister coming through. And so, a first date of sorts is arranged between Joe and Dottie, where, after a jovial serving of tuna casserole, he demands that she strip and coolly stages her deflowering through a series of precise orders, to which Dottie complies, albeit with a strain of internalized reluctance. Joe is nothing if not methodically precise. He demands good manners, and upon his arrival in any scene, shows his absolute control over the other players. But underneath his suave exterior is a kind of psychosis that’s not fully revealed until the film’s unsettling conclusion that, the disturbing “K-Fry Chicken” sequence aside, depicts sheer lunacy. There’s a moment when Joe snaps suddenly and destroys the TV, which always seems to be blaring some monster truck nonsense because it’s impolite to have the TV on during a serious discussion.

McConaughey gives a slick and sadistic performance, using his natural southern charms and onscreen authority to make his killer instantly the most watchable character onscreen. His motions are deliberate, sexy, and creepily methodical, but also devilishly charming in a way only McConaughey can be (see The Lincoln Lawyer or Magic Mike). Like him, the rest of the cast is superb. Haden Church’s dry, knows-he’s-dim role results in a constant stream of belly laughs, even when the film reaches its grisliest moments. One thing the viewer doesn’t expect is how funny Killer Joe proves to be, due in large part to the Sideways actor. Hirsch, meanwhile, remains the ever-hapless high-energy protagonist, whose pathetic desperation could use a little more planning. Gershon is effective as bitchy trailer trash and doesn’t show much dimension until she’s traumatized in a notorious drumstick fellatio scene near the end. But it’s Temple’s performance that remains so deceptively complex; her duality within her situation stands as the film’s big question, on which the bloody, ghastly, open-ended finish hinges.

Beyond the performances, which are the film’s highlight, Friedkin’s technical approach demands notice, as his formal presentation hasn’t been this composed for decades. Using aggressive editing to mirror the story’s tone, editor Darrin Navarro (who also assembled Bug) employs abrupt jump cuts that convey a sort of disjointed montage during a chase scene and in the explosive end. Cinematographer Caleb Deschanel, who worked with Friedkin on 2003’s The Hunted, captures rainy, sloppy, trailer park palettes and a certain crispness in the daytime chases and meetings in abandoned pool halls, but especially in eerie dream sequences. The mood of the finale is wonderfully shot and lit, most of it from a distance to evoke the stage play origins of the piece. When the lights are dimmed for the family’s last meal, the mood is excruciatingly weird and dark, but it looks gorgeous and totally transfixes the audience into the disquieting scene.

Still, one must not dwell too much on the sex and violence in this picture, of which there is much. It doesn’t encapsulate the film; it just adds a necessary and intentionally over-the-top flavor to this vicious farce. Violence spills out in harsh beatings, ugly bruises, broken noses, and bloody faces, while the sexual content never feels like it’s trying to be enticing, just sordid. Underneath that which resulted in the NC-17 rating are colorful characters and wild performances interacting in the blackest of black comedies you’ll ever see. Of course, Killer Joe isn’t for everyone. It’s the kind of film that prompts the theater manager to announce beforehand, “there are no refunds after the first thirty minutes” because attendees have been asking for them. In other words, you should know what you’re getting into. And chances are, if this material sounds intriguing to you right now instead of appalling, no doubt you’ll love what a juicy, ferocious film Friedkin and Letts have unleashed.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review