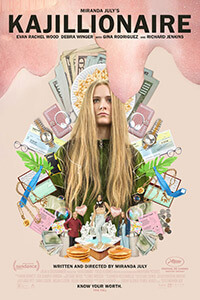

Kajillionaire

By Brian Eggert |

Miranda July tells stories about introverted people who have trouble feeling that they are part of the world around them. Maybe that’s why her films occasionally feel like an alien’s perspective on humanity. The wildly eccentric multimedia artist and filmmaker returns after nearly a decade with her third film, Kajillionaire, following her heartfelt and funny debut with Me You and Everyone We Know (2005) and the less charming but no less idiosyncratic The Future (2011). July’s latest is both a condemnation of familial codependency and a call to emotional freedom, even while it acknowledges our desperate need to be loved. Though populated with the abnormal characters and scenes of their bizarro behavior one has come to expect from her work, July’s film uses whimsical and irregular details to comment on the substance of everyday life. Kajillionaire is a family portrait of sorts. But like her central characters, her film only seems to exist on the margins—while they, the family and the film, actively try to resist clichés and conformity, they also embrace them in unexpected ways.

Anchored by several weird, albeit inspired performances, the story follows the Dyne family, a disheveled bunch captained by the jittery Robert (Richard Jenkins) and hardened Theresa (Debra Winger). They don’t seem like the type to have had a child, and perhaps that’s why their 26-year-old daughter, Old Dolio (Even Rachel Wood), appears trapped in a state of confusion and arrested development. Rigid and unable to make eye contact, Old Dolio hides behind her long hair, tightened face, baggy clothes, and the artificially lower-pitched voice of Elizabeth Holmes. Actually, Wood’s physicality and inflection recall a young Keanu Reeves, as though she’s playing an awkward surfer dude with intimacy issues—not what someone would call “hooked on life.” Together, the Dynes live off the grid in a cheap business space next to a pink bubble factory, sleeping on cubicle floors. By day, they avoid security cameras and steal mail from the post office. Old Dolio explains later that they split everything three ways, but they also divide the costs three ways, thus robbing the child of any real parental support.

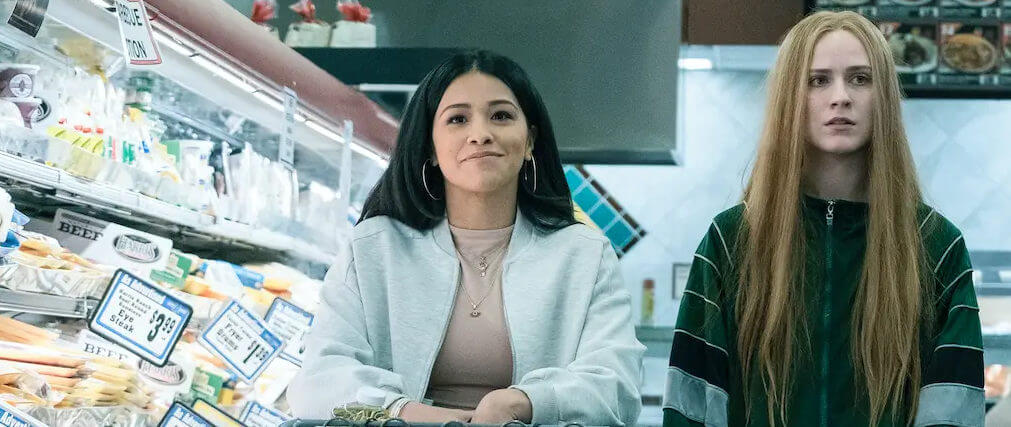

Kajillionaire borrows a thread from both Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Shoplifters (2018) and Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019), in that the Dyne family survives through theft and con artistry. But two significant events occur that force Old Dolio to question her family’s lifestyle: First, as part of a scam, she attends a maternity class and learns about the breast crawl. She wonders if she crawled to her mother’s breast as an infant or, as the instructor implies of children placed on a cot instead, she and her mother failed to form an instinctual bond. Later, her parents meet Melanie (Gina Rodriguez) on a plane. A bright and curious personality who quickly accepts and joins the Dyne’s schemes, Melanie is immediately drawn to this family, causing Old Dolio some jealousy but also something more. She tells Melanie at one point, “Stop wearing such tight clothes. You’re making everyone uncomfortable.” Perhaps because of the hinted attraction, Melanie agrees to help them acquire enough money to pay some overdue rent. However, July’s script doesn’t adequately explore Melanie’s inner life—to the extent that, eventually, she begins to feel like a device to break Old Dolio out of her shell.

But admittedly, the film proves unsympathetic until Rodriguez appears onscreen, bringing unmeasurable personality and exposing the humanness of these often unlikable characters—increasingly so, as Melanie drives the Dynes to reveal their true selves. She agrees to help them con lonely seniors out of their antiques, but she’s shocked to discover how far Robert and Theresa will go to make the rent. And the couple also has more salacious motives for befriending Melanie that go forgotten almost as soon as they’re introduced. Meanwhile, in fleeting moments where her family must feign normalcy to convince a mark, Old Dolio gets a sense of what life would be like in a “normal” family; her parents neither know how to show affection nor believe she has an interior life. Speaking of Melanie, Theresa tells her daughter, “She has tender feelings. You couldn’t know anything about that.”

However grim and rather depressing this may sound, July directs with a subtle comic energy that carries her audience from scene to scene. You won’t laugh a lot, but you’ll smile plenty. Though eventually, we anticipate where the story will lead. Most surprising is an allusion to the previous life maintained by Old Dolio’s parents, which she knows nothing about. After all, they weren’t always like this—at some point, they chose to bring a life into this world, despite their refusal to become “false, fakey people.” July seems to suggest there’s a balance between nonconformity and offering a child its needed emotional support. When Old Dolio eventually discovers a new support system, it’s achingly endearing. Kajillionaire manages to be both stilting and difficult to access in the first half, but there’s an overwhelming rush by the final moments. It’s the sort of film that will benefit from a second viewing if only to anticipate the heartwarming resolution.

To be sure, for all of July’s quirks and visual peculiarities, her brand of filmmaking fits an indie narrative structure that manages to be universal in its oddball specificity. It’s the sort of film that could be described as having a Sundance aesthetic, even if it hadn’t debuted at the festival earlier this year. If that sounds somewhat harsh, it’s only because July has made more daring and strange films before, leaving Kajillionaire to feel relatively conventional. Sure, cinematographer Sebastian Wintero’s fluid camerawork and wide-angle lenses reveal an off-kilter world, while the circular music by Emile Mosseri reveals how Old Dolio is trapped in a state of comfortable repetition with her unhealthy family, a kind of limbo. But the film’s end result feels like standard stuff presented in a playfully bizarre yet entirely safe way.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review