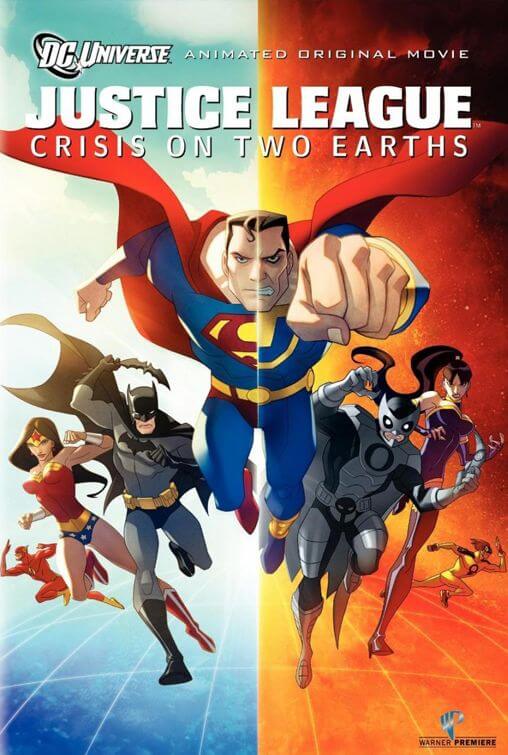

Justice League: Crisis on Two Earths

By Brian Eggert |

A year ago, if you’d asked me to list the premier animators working in the medium today, I would’ve told you Pixar, Hayao Miyazaki, and Warner Bros. Animation. Through their partnership with DC Comics, Warner (under the Warner Premiere label) has released a number of superhero-based direct-to-video features such as Green Lantern: First Flight, Justice League: The New Frontier, and Wonder Woman, all rated PG-13 for their adult-centric presentation. In the visual style of the studio’s Batman, Superman, and Justice League television shows from the 1990s and beyond, the quality of the features rivals that of most modern live-action superhero films, and certainly outclasses the animation departments at Dreamworks and Fox in terms of storytelling.

And after several stellar releases in a row, suddenly the studio began receiving some acclaim from both critics and comic fans. The DVDs and Blu-rays sold hundreds of thousands of copies, and because they were relatively cheap to produce, the productions were very profitable. And what do companies do when they find they have a profitable product? Find a way to make it more profitable. If well-made animated features could make money, think what would happen if they just threw a quick product together—imagine the profits then. Such is the explanation for drivel like Superman/Batman: Public Enemies, and their latest feature Justice League: Crisis on Two Earths.

From the quality of the animation to the nature of the characters, Warner’s latest foray into DC superhero territory feels inferior. The potential story is there, but Warner has limited itself by taking on a massive scope with much too short a running time (roughly 75 min.), leaving the audience dissatisfied with what little we’re shown. The vast setup of the story is an abbreviated take on a graphic novel by Grant Morrison, called JLA: Earth 2, but there were similar stories told back in the 1960s comics. The scenario involves alternate realities, and the superheroes/villains of those worlds running amuck in our reality, and vice versa.

The concept falls back on the theory of infinite realities, that for every decision or event in time, an alternate reality is created. As one character points out, there are infinite realities that are similar, differentiated only through the smallest details. But there are also fantastical worlds. For every Earth, for example, there are an infinite amount of Earths within these alternate realities. There’s an Earth where The Beatles never existed. There’s an Earth where humans never evolved. There’s an Earth where you called in sick to work this morning. There’s an Earth where you’re married to Jennifer Aniston. And so on, from the most insignificant differences to the most crucial. However impossible, if it could happen, it probably did in another reality. But all of these realities stem from a single source, called Earth Prime.

In the first scenes, Lex Luthor, one from an alternate reality where he’s a superhero, comes to our reality to gather the Justice League (Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, et al.) for a special mission. He needs their help to stop a group of villains, conspicuously called The Crime Syndicate, from taking over his version of Earth. This Syndicate contains the evil opposites of the heroic Justice League. Structured like the mafia and led by Ultraman—the Goodfella-Superman, complete with the badda-bing accent—the Syndicate threatens to blow up their Earth with a massive bomb built by their Batman equivalent, Owlman. The stakes are higher than they think, however, as the nihilistic Owlman plans to travel across dimensions to Earth Prime and set off his bomb, thus destroying all realities.

(Note: If there’s one reality featuring Owlman, doesn’t that mean that potentially millions of realities with other versions of Owlman exist, all of whom have the same idea to blow up Earth Prime? The Justice League only stops one Crime Syndicate throughout the course of the movie. Maybe they just assumed that other Justice Leagues were stopping those Owlman variants. Still, wouldn’t there be at least one reality where Owlman wasn’t defeated and therefore succeeded in destroying everything? If so, perhaps the movie should have ended with a question mark. It’s worth philosophizing.)

Maybe I’m overly dedicated to the canon of the animated series, where the voicework of Kevin Conroy as Batman, Mark Hamill as The Joker, and Tim Daly as Superman feels standard. Here, those originals don’t reprise their voice roles for whatever reason. Obscure celebrities like Mark Harmon, James Woods, and Chris Noth provide the voices here. It’s a superficial concern, but when Brian Henson started doing the voice of Kermit the Frog, people noticed. Warner Bros. established its fanboy base with those original actors, and since that fan base makes up the studio’s otherwise minor market for these direct-to-video features, it would make sense to appease the audience’s expectations with a simple thing like casting. Alas, Batman and Superman do not sound like themselves for those familiar with Warner’s ever-expanding DC universe.

How the mighty have fallen… Warner Bros. Animation went from creating theater-worthy movies on video to creating cartoons barely worthy of TV. More than just some voicework here and there, the movie feels disconnected from its audience from an overabundance of characters. The viewer becomes numb to superhero action when there are a dozen or more battling onscreen. Whatever happened to just Batman vs. The Joker or just Superman vs. Brainiac? How refreshing it would be if this studio went back to some real storytelling again, instead of just trying to move some product through an extreme amount of superhero violence. The brief runtime only underscores this problem, as none of the many characters feel three-dimensional, despite the enormous potential behind the serious-minded, high-concept plot reminiscent of Watchmen being presented.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review