Jurassic World Dominion

By Brian Eggert |

The poster claims Jurassic World Dominion is “The Epic Conclusion of the Jurassic Era,” signaling the supposedly final chapter in the franchise. It’s a claim that should leave any viewer doubtful. Will Universal Pictures really end a series of blockbuster movies that have generated billions in revenue not just from ticket sales but also from toys, theme-park rides, books, video games, promotional tie-ins, t-shirts, and lunch boxes? Decidedly not. But until there’s another reboot in ten years (probably less), that’s the tagline Universal has chosen. And to end their hit-or-miss series of films, they’ve released the longest entry to date. Even at a whopping 146 minutes, the movie somehow feels like the filmmakers had to trim footage in ungainly ways to reach that runtime. In the spirit of fan service, they’ve also brought back the beloved main cast from Steven Spielberg’s original Jurassic Park (1993) and its two sequels (in 1997 and 2001), and combined them with players from the update, Jurassic World (2015) and Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018). Along with some new dinosaurs and a timely theme about the ecological dangers of genetic modification, Dominion matches its giant-sized creatures with a behemoth scope of characters, locations, and storylines that, in their shortcomings, never supersede the lizard-brained joys of watching dinosaurs wreak havoc.

Colin Trevorrow returns to the director’s chair for Dominion after a rocky few years. After seeing his quirky indie comedy Safety Not Guaranteed (2012), Spielberg hand-picked him to helm Jurassic World. But Trevorrow’s subsequent work—on The Book of Henry (2017) and an unrealized stab at Star Wars: Episode IX – The Rise of Skywalker (2019)—has been panned. Even so, like many filmmakers of his generation, Trevorrow grew up on a diet of Amblin Entertainment productions, and he replicates that Spielbergian style well enough in Dominion. For example, watch a brief moment where a T-rex approaches, and its head appears framed within a circular sculpture, creating the Jurassic Park logo—it’s a visual gag that not only recalls the Batwing-in-the-Moon sequence from 1989’s Batman, but it’s characteristic of Spielberg’s playful flourishes. Along with obligatory nostalgia and self-reflexivity via callbacks to the original, Trevorrow operates in the familiar-but-new mode that has defined the Jurassic World movies: Jurassic World refashioned Jurassic Park, and Fallen Kingdom mirrored The Lost World. Fortunately, Dominion doesn’t exactly replicate the underwhelming Jurassic Park III; it has more on its mind, perhaps too much.

As if recent Hollywood tentpoles weren’t bloated enough, screenwriters Trevorrow and Emily Carmichael cram enough plot for four Jurassic movies into Dominion. Dinosaurs have become commonplace and almost normalized in the new movie. Four years after the events of Fallen Kingdom, both humanity and Nature find ways of spreading the dinosaur population across the globe, and there’s an awkward adjustment period to the new biodiversity. Besides reproducing on their own, dinosaurs also journey across the planet with the help of illegal breeders and black marketers. It’s all conveniently summed up in an expositional news broadcast that recaps the series thus far and identifies a potential solution: Lewis Dodgson (Campbell Scott), a shady character who had a brief appearance in the original. Now presenting himself as a Jobs-like tech giant, Dodgson runs Biosyn (“Bio-sin,” as in crimes against Nature, get it?), a corporation committed to collecting dinosaurs and preserving them near its HQ isolated in a valley in the Dolomites. In this, Dominion offers a variation on a theme—the dinosaurs don’t break out of a theme park; the humans have to break into their sanctuary.

The disjointed first hour of Dominion hops across the globe to reestablish our heroes and chart their course to Biosyn. Unfortunately, Trevorrow and editor Mark Sanger rush through these scenes, offering each character a shorthand recap and robbing them of any depth. Claire (Bryce Dallas Howard), still a dino-rights activist, lives in the Sierra Nevadas with her makeshift family: dino-whisperer Owen Grady (Chris Pratt) and Maisie (Isabella Sermon), the 14-year-old girl engineered by a former Jurassic Park geneticist. Alan Grant (Sam Neill) keeps his old-school paleontology digs alive in Utah, where his speech about the importance of his work is awkwardly cut short when his old friend, Ellie Satler (Laura Dern), shows up asking for a favor. In West Texas, she finds evidence of a genetically modified swarm of enlarged locusts eating up crops—all except, conveniently enough, the fields of GMOs engineered by Biosyn. And so, Ellie and Alan set out to find proof of Biosyn’s intended seed-monopoly scheme that could result in worldwide famine. Later, they meet up with Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum), who, in a nonsensical turn, lectures at Biosyn HQ about the dangers of playing god with genetics. Elsewhere, Dodgson pays mercenaries to kidnap Maisie and the infant Velociraptor belonging to Blue (the Velociraptor who bonded with Owen in Jurassic World), setting Claire and Owen on a pursuit across the globe.

While various plot strains push everyone to Biosyn in scenes that feel trimmed and truncated to move the story along, the movie offers plenty of spectacle. A sequence in the dinosaur black market—complete with dinosaurs for sale, placed in death matches, and barbecued for dinner—shows that human beings always find ways to exploit a resource. A tense chase involving Atrociraptors trained to attack a laser-targeted objective leads to a zippy sequence through the streets of Malta, then onto a cargo plane piloted by the rugged and independent Kayla Watts (DeWanda Wise). All the while, Owen demonstrates that his tactic of holding a single hand up to dinosaurs in a “stop right there” gesture will, absurdly, prevent reptiles large and small from attacking (don’t try this in the wild, kids). The writers don’t give Pratt much else to do besides running from or giving commands to dinosaurs. Then again, few cast members get compelling dialogue or dramatic arcs thanks to the overstuffed screenplay. So it becomes a question of who has the most onscreen appeal, and the answer is invariably Dern, Neill, Goldblum, Howard, and the newcomer Wise. Whenever they’re in a scene, their sheer presence commands our attention—particularly in the chemistry between Alan and Ellie, rekindling their allusive romance from the 1993 film.

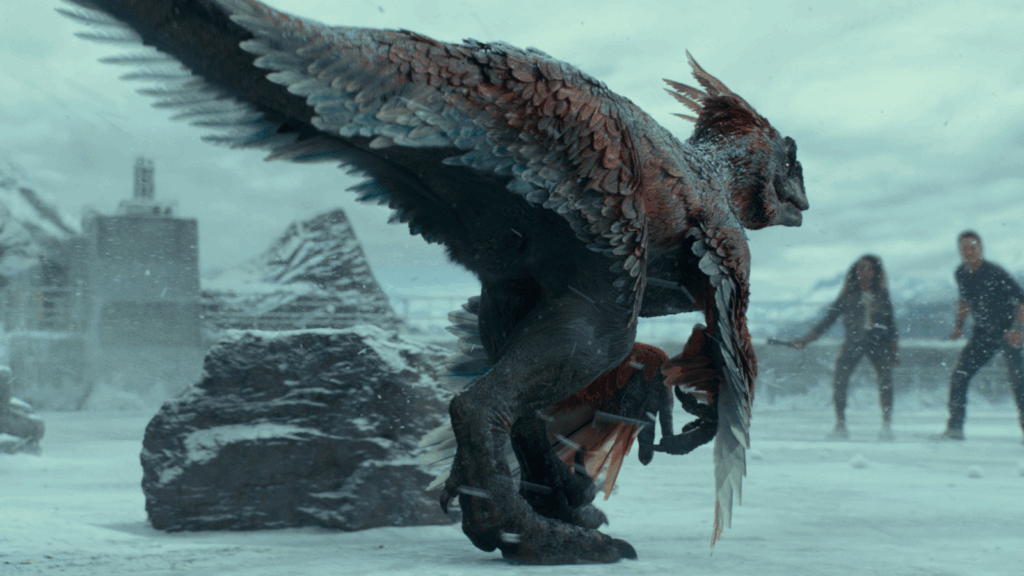

As for the dinosaurs, Dominion introduces a few strange and exciting varieties. A red-feathered Pyroraptor stands out in a thrilling icebound scene. A birdlike and towering Therizinosaurus—a near-blind beast, armed with massive talons—occupies a breathless sequence involving Claire hiding underwater for safety. The resident Big Bad is the Giganotosaurus, a spikier and slightly bigger version of a T-rex (though Grant calls it Earth’s largest carnivore, it looks smaller than Jurassic Park III’s Spinosaurus). But the Giganotosaurus doesn’t have a personality, such as the Indominous-rex psychopathic behavior in Jurassic World, and it comes off as rather nondescript by comparison. And then there’s the T-rex, which functions in hero mode, conveniently rescuing the puny humans in moments that test even blockbuster logic. The good dinosaurs practically nod at humans with gestures of approval, and two victorious dinosaurs all but high-five after a climactic scene in a ludicrous moment. But somehow, these miracles of modern science, implemented with a refreshing combination of puppetry and CGI, tend to feel secondary and devoid of awe in Trevorrow’s hands.

Beneath the movie’s overpopulated cast of heroes and dinosaur adventure, Trevorrow and Carmichael underline a commentary about the supremacy of Nature and the dangers of GMOs. Similar conversations have been embedded into this series since the original, but in today’s world of limited seed diversity, climate change, environmental disasters, and the proliferation of genetic modification with unpredictable consequences, Dominion’s message resonates. That is, until it becomes a mixed message with the genetic manipulation of Maisie’s DNA by the redeemed Dr. W (BD Wong) to save the world from the locusts he helped create. Worse, a clunky montage of animals and dinosaurs living in harmony at the end suggests that we should all “coexist.” Maybe the message is intended to underscore our divisive times, implying that the opposing ideologies and political factions among humans should endeavor to inhabit the same planet peacefully. It’s a noble message, to be sure, albeit delivered with images of dinosaurs living peacefully alongside animals that should be their prey—Pteranodons flying among ducks, a colossal Mosasaurus next to whales—as though they’ve made a conscious decision to live together with tolerance and in peace, to the extent that carnivores become herbivores. It’s an idyllic if impractical visual that ignores the sublimity of Nature in its equal measures of beauty and brutality.

Somewhere along the way, Dominion stops feeling like a megabudget when-animals-attack movie and starts to feel cumbersome and self-important. Despite that, it remains superior to The Lost World and Fallen Kingdom, the duds of the franchise. Though its convoluted plotting tends to feel padded, the dinosaur action—the raison d’être here—has been capably rendered by Trevorrow and cinematographer John Schwartzman, though it lacks Spielberg’s raw virtuosity and wonder. If the filmmakers haven’t found new ways to make dinosaurs thrilling without genetic splicing or adding lasers, it helps that the actors haven’t lost their appeal: Goldblum’s utter Goldblumness as Ian Malcolm, Dern’s command of every frame, Neill’s radiating charisma, and Howard’s pathos in her character’s newfound sense of responsibility. Still, audiences making the journey to the theater will doubtlessly enjoy the ride with a bucket of popcorn and a soft drink in hand. Over two-and-a-half hours, viewers will find enough to keep their attention. Just don’t expect the experience to last much beyond the end credits or hold up under scrutiny.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review