Jurassic World

By Brian Eggert |

Universal Pictures and producer Steven Spielberg have been faced with a predicament since the release of Jurassic Park. Spielberg’s 1993 blockbuster shattered box-office records and launched a new wave of digital cinema with its still-impressive implementation of CGI. But if you’ve seen one computer-generated dinosaur, you’ve seen them all. The filmmakers have since struggled to understand that and delivered underwhelming sequels in 1997 and 2001, light on characters and heavy on dinosaur mayhem. Perhaps with that in mind, it took fourteen years to develop a worthy sequel after the dull Jurassic Park III. And while the franchise’s latest attraction, Jurassic World, still hasn’t figured out that it’s not the size of the dinosaurs that matters, it’s the depth of characters, the new film at least betters its two predecessors. By embracing the original’s theme-park-gone-haywire scenario, complete with Spielbergian family bonding, the new film embraces its close resemblance to the original with a refreshingly self-aware playfulness. And yet, even while admitting that it’s somewhat obligated to be “bigger, louder, and have more teeth,” it also delivers perfect escapist summer entertainment.

Spielberg directed the initial adaptation of Michael Crichton’s novel and its follow-up, The Lost World: Jurassic Park, before handing the reigns to Joe Johnston for number three. After poor critical and fan reception, he sought fresh blood for number four. Spielberg took a meeting with Colin Trevorrow, whose only film credit was an idiosyncratic romantic comedy—also sort of about time travel—called Safety Not Guaranteed (2012). The legendary director saw Trevorrow’s low-budget freshman effort and soon offered him a $150-plus million budget to direct the fourth Jurassic Park film. But Trevorrow wanted nothing to do with the script he was handed. Instead, he demanded that he and his previous collaborator, fellow NYU film student Derek Connolly, be allowed to rewrite their own, personalized draft—a ballsy mandate given who was making Trevorrow the offer. Nevertheless, Spielberg conceded with only three required elements: a fully operational park, a park trainer with the trust of his animals, and a new dinosaur that escapes captivity. And aside from Spielberg’s notes as an involved executive producer, at times Jurassic World feels just as idiosyncratic as Safety Not Guaranteed, but within the limitations of a dinosaurs-chase-humans scenario.

“No one’s impressed with dinosaurs anymore,” remarks a character early on, suggesting what the original’s two lackluster sequels already proved—that a movie about nothing more than dinosaurs on the loose, eating humans and wreaking havoc, has lost its charm since Spielberg’s first “Jaws on land” release. Fortunately, Jurassic World’s self-conscious streak acknowledges the difficulty of sustaining a franchise through one-upmanship. Not only does it deliver bigger, badder dinosaurs, but it also underscores how absurd it is that audiences no longer find dinosaurs interesting on their own. Co-writers Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver, who share credit with Connolly and Trevorrow, put the long-operating island theme park “Jurassic World” in a similar dilemma. On the Costa Rican isle of Isla Nublar, park manager Claire (Bryce Dallas Howard) bows to the park’s billionaire owner Masrami (Irrfan Khan), who demands toothier dino-attractions after profits enter a slight valley.

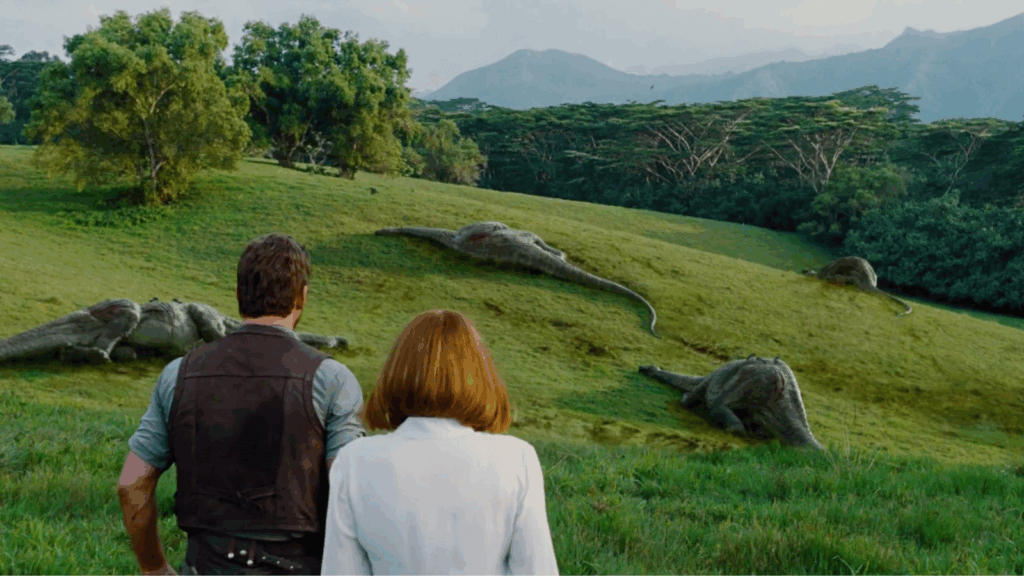

Life imitates art, or at least moves along a similar path in this case. Courtesy of John Hammond’s former geneticist Dr. Henry Wu (BD Wong, reprising his role from the original), the park’s latest attraction will be a creation called Indominus rex—an engineered hybrid of a T-rex and who-knows-what-else. Dubbed “Verizon Wireless Indominus rex” by investors, this uncannily smart creature is to Deep Blue Sea (1999) what Jurassic Park’s T-rex was to Jaws. It’s a thinking, problem-solving, malicious monster with some unique traits, including a nifty camouflage trick; it’s also a vicious killer that pushes the PG-13 label. Elsewhere, the old standard dinosaurs show up (Brachiosaurus, Triceratops, Stegosaurus, etc.), but there are some new species too, including an impressive underwater creature—one that chomps down on a Great White Shark like a seal would a minnow, as if to out-do Jaws. At any rate, inevitably, the I-rex busts loose in what an automated voice hilariously calls a “containment anomaly,” sends everyone in the park screaming for their lives, and requires action from the human cast members. Once the I-rex escapes, Claire, obsessed with control (as indicated by her angular hair and clean, white getup), struggles to maintain composure as the creature tears through the park’s security measures and begins killing other animals with murderous abandon.

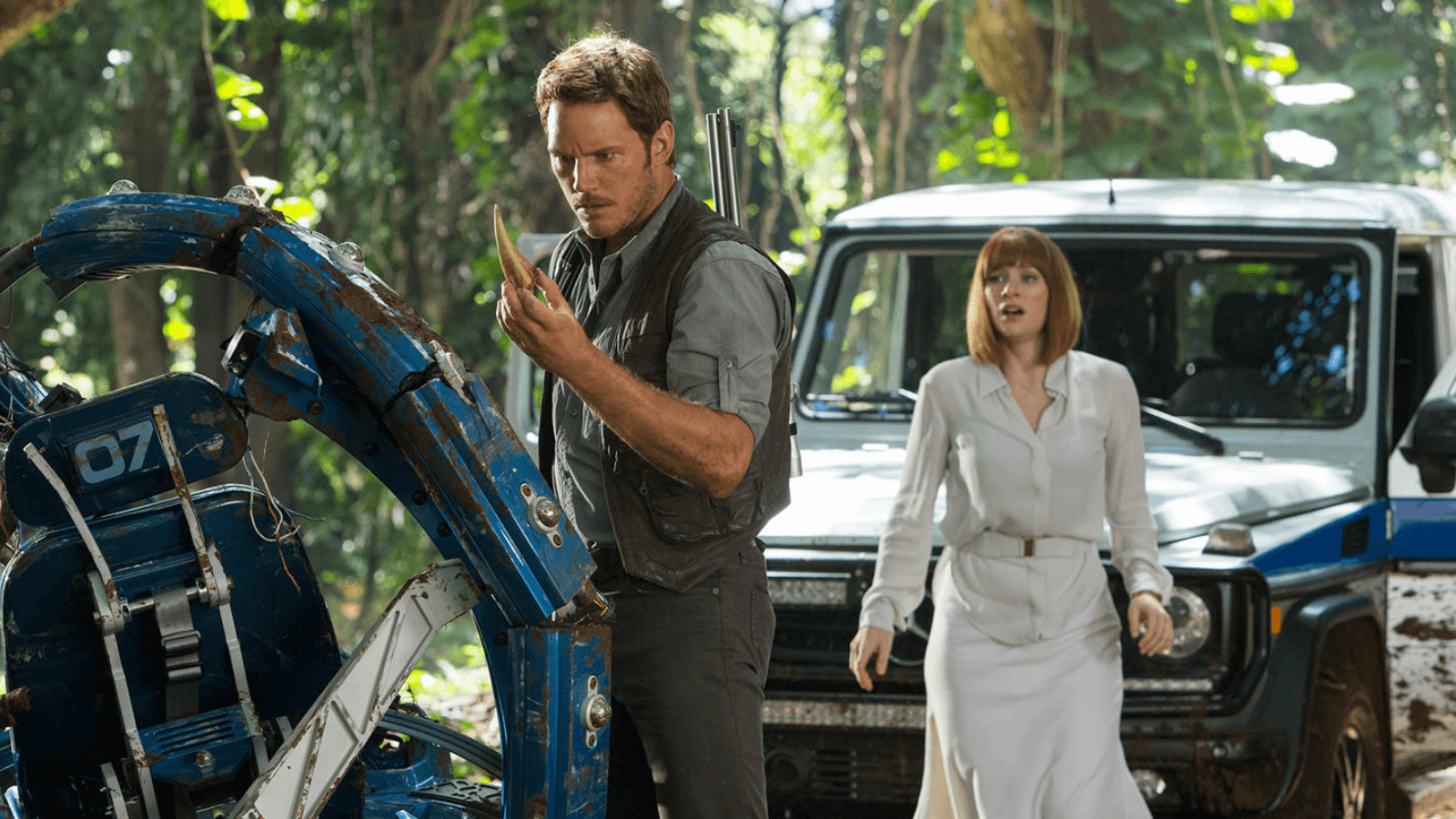

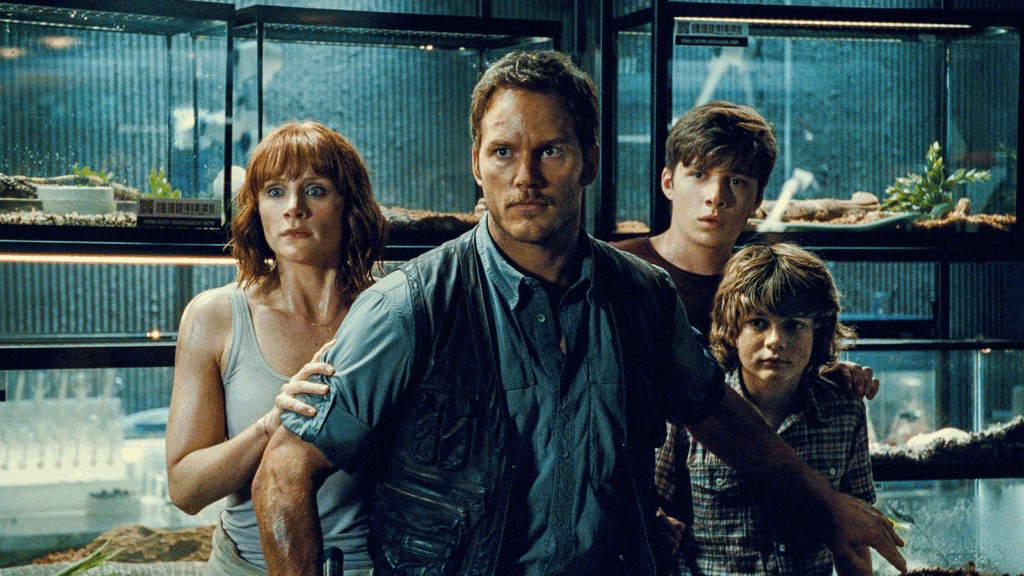

Meanwhile, Claire’s nephews have been sent to the park as their parents (Judy Greer and Andy Buckley) wrap up divorce proceedings on the mainland. Moody, hormonal teen Zach (Nick Robinson) and his younger, dino-crazed brother Gray (Ty Simpkins) were supposed to spend the week with Claire, but she’s a businesswoman, allergic to kids, and far too preoccupied. Just as the park rides shut down and emergency containment procedures begin, Zach and Gray are, of course, still exploring the park and require rescuing. Enter Owen Grady, the sarcastic ex-Navy man played by Chris Pratt, fresh off his star-making turn in Guardians of the Galaxy. This quipping slab of machismo has tamed a pack of Velociraptors, the smarter-than-average dinosaur species that remains a series favorite. Though they don’t use their six-inch claws on a scratching post quite yet, they listen enough to resist making Grady lunch. Now frantic and out of her comfort zone, Claire joins Grady, with whom she has a romantic past, to recover her two visiting nephews. At the same time, a military contractor (Vincent D’Onofrio) working for InGen, the company behind “Jurassic World,” wants to use Grady’s Velociraptors for hunting down the I-rex—to test them for possible military applications. This is such a gloriously bad idea that you just know it’s going to end up bad.

Much of what happens you could probably see coming if you took yourself out of the experience. Jurassic World follows the basic outline of the 1993 film, occupying a small laundry list of formulaic characters and situations gleaned from the original; however, they’re all delivered with expert aplomb. Trevorrow keeps us rapt from start to finish with fast pacing, an energetic script, and solid direction. He doesn’t give us an opportunity to think about what’s coming. Granted, he doesn’t deliver as many iconic visual moments as a master like Spielberg did in Jurassic Park, but his execution is confident. Certainly one could accuse the film of relying too heavily on CGI to create its dinosaurs, as the production almost entirely avoids practical or animatronic effects. CGI technology apparently hasn’t improved much in 22 years, because the creatures look comparable to those in the original, and at times less convincing. For example, the final battle between an array of dinosaurs in the park’s downtown area becomes somewhat difficult to follow and, for being the film’s big showdown, plays somewhat clumsily. Rendered with better VFX and more fascinating overall are the horrific possibilities of the I-rex—its scary intelligence and unexpected predatory traits, all gathered from various DNA sources. Why would anyone make such a monster? you might ask. That’s a question left for an inevitable sequel.

Jurassic World is at its best when it replicates the theme park experience: the advertising, crowded walkways, monorails, and petting zoos—all through a sardonic lens. Kudos to Trevorrow and production designer Ed Verreaux for recreating the look of “Jurassic World” to mirror Disneyland and the Universal Studios theme parks. Their shops, restaurants, IMAX theater, cross-promoting, and general “main street” layout create a familiar theme park experience for the viewer. The park itself is as much a character as New York City in every movie that takes place in New York. As for the humans, Claire is the only character with a fully developed character arc, and Howard is charming in the role. The others are standard archetypes. But even clichés can work when properly implemented; that’s why they’re clichés in the first place. Claire’s character is by no means static, as her icy exterior eventually melts into a heroine of sorts, and one with a new-found motherly instinct no less. But the fact that she refuses to remove her heels in the jungle deserves an eye-roll. Pratt is suitably heroic and at times jokey, though not quite so much as Star Lord. Simpkins is joyful and rambunctious, echoing his role from Iron Man 3. Khan’s eccentric millionaire remains likable, but like Hammond, the character is ignorant of the moral implications of genetic experimentation.

To be sure, Jurassic World is not without subtexts relating to the genetic modification of animals or even produce—the point being that tampering with Nature usually has side effects. Whether it’s genetically modified corn being fed to a chicken pumped full of antibiotics, hormones, and any number of other unnatural chemical catalysts or an ultra-intelligent dinosaur bent on eating everything in sight, the message is the same. One might also glean a message of animal rights activism from the proceedings, given Grady’s sympathetic understanding of the dinosaurs’ needs as animals that learn from their surroundings and experiences. But such ideas are buried beneath the surface of Trevorrow’s popcorn-munching treatment, which contains all the usual signs of a rousing Hollywood blockbuster. Despite the film being very standard stuff, the screenplay allows for quirky moments that keep us chuckling. Jake Johnson appears as a control room techie and has some hilarious lines, including a wonderful moment when he assumes a hero role for misguided reasons. The romantic banter between Pratt and Howard is typical, but it works because the performers are likable, and the situation keeps us in the moment. Trevorrow fully embraces the summer movie tentpole-style and, considering this is only his sophomore effort, nails it.

In previous sequels, Jurassic Park’s romanticism toward dinosaurs was replaced with monster movie mechanics. Much as Claire keeps the dinosaurs at a distance as “attractions” or “assets,” audiences have learned to view these creature effects with a level of detachment—unable to suspend our disbelief, in part because the storytelling in The Lost World: Jurassic Park and Jurassic Park III was so lazy. Not only was the awe and wonderment of the original gone, but the suspense was gone too. Perhaps best of all, Jurassic World makes us feel something for dinosaurs. Through the course of his film, largely through Grady treating dinosaurs as animals that, like any other creature, must be taught and developed, we become invested in their behavior patterns, therein making dinosaurs more real for our experience. During one somber scene, you may come to tears as a dying herbivore takes its last breath. In another scene, you might gasp at the possible death of your new favorite Velociraptor named “Blue.” Other scenes, including several effectively executed chase sequences, create thrills that make the audience tense up or jump in their seats. Not since Spielberg’s original film has this franchise been able to induce such reactions. Jurassic World resolves to be more than another by-the-numbers entry in a highly commercial moneymaking franchise; it’s sharp, well-made, knowing entertainment that’s also the first sequel worthy of the original masterpiece.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review