Jurassic Park III

By Brian Eggert |

Jurassic Park III is content to serve the basic B-movie needs of its audience. The second sequel to Jurassic Park (1993) doesn’t bother waxing philosophical about the moral implications of genetically engineered dinosaurs, nor exploring its human characters in any meaningful way. The filmmakers have stripped the whole people-chased-by-dinosaurs-on-an-island to its bare essentials. And while the material feels like more of the same, it adds some new dinosaurs to the series—including one that’s bigger, badder, and meaner than the Tyrannosaurus rex—and therein offers a small degree of variety, whereas skilled actors slum it for a script that’s hardly worthy of their talent. The writing is a patchwork of familiar ideas and forgotten asides; though Michael Crichton did not write a third Jurassic Park novel, there was plenty of leftover material in his two books for this entry to borrow. Clocking in at a brisk 90-minute runtime, more than a half-hour shorter than its predecessors, the film is a serviceable theme park ride, propelled by CGI monsters, PG-13 rated blood and guts, and paper-thin characterizations unworthy of Spielberg’s 1993 original. But it’s also kind of fun.

With millions of dollars waiting to be earned, a sequel to 1997’s lackluster The Lost World: Jurassic Park was inevitable. Spielberg, who labored through shooting the sequel, gave up control to his friend and collaborator Joe Johnston this time. The franchise’s new director had experience helming digital creatures alongside real-life humans—an increasingly popular special effect in Hollywood after the original Jurassic Park. Johnston’s entertaining board game movie Jumanji (1995) featured jungle animals on the loose in suburbia and, in a way, served as an audition for Johnston to direct a dino-sequel, which he had been interested in ever since seeing the original. Whereas Spielberg wanted control over The Lost World, he promised the third entry would go to Johnston. Development began in 1999, with a screenplay eventually credited to Peter Buchman, Alexander Payne, and Jim Taylor, although several script doctors were hired and the original’s writer David Koepp was consulted. Before anyone involved had a complete working script, filming began, and new pages would arrive on the set daily.

After all, there’s a preset release date to make and a franchise to maintain. Indeed, titles like Jurassic Park III are less concerned with the end product than the franchise having another product to peddle. Selling video games, lunch boxes, toys, and comic books is more important than the quality of the finished film. At least Johnston remains talented enough to deliver a suitable distraction for the film’s $93 million price tag. His blend of animatronics and CGI looks more convincing than the digitally dominated creations for The Lost World, and there’s a believable sense of jungle atmosphere in several sequences. Moreover, the small ensemble of actors is slightly more interesting than those in The Lost World, which isn’t saying much—that film’s dull cast also committed the crime of overdosing audiences on Jeff Goldblum’s quipping, now-sidelined mathematician Ian Malcolm. From the original, Sam Neill returns as the studious Dr. Alan Grant, and Laura Dern appears in a forced cameo as his ex, Ellie. William H. Macy and Téa Leoni, ever-stimulating performers, appear as a bickering married couple.

Another child in peril, another “lucky bag” that saves someone from falling, and another crackpot theory about dinosaurs proved correct. The story finds any excuse it can to return to Dinosaur Island. When a pair of tourists, one of them the 12-year-old Eric Kirby (Trevor Morgan), decide to parasail near the island to catch a glimpse, a crash strands the sole surviving adolescent on the island. Macy and Leoni play Eric’s divorced parents, Paul and Amanda, who pose as a wealthy couple to deceive Grant and his assistant Billy (Alessandro Nivola) into providing a flyover tour of the island. The Kirbys have also hired three mercenaries (Michael Jeter, John Diehl, and Bruce A. Young) to fly the plane and provide armament support. Within moments of landing and searching for Eric, their deception is clear. Grant wants off the island, especially because his check isn’t going to clear. (NOTE: If someone pays you to visit Dinosaur Island, be sure the check clears first.) In short order, a colossal Spinosaurus brings one merc to tears, destroys their plane, chomps down two mercs, and takes down a T-rex in a fight. The survivors flee into the jungle, hoping to meet up with Eric along the way. Of course, Eric is fine, surviving Lord of the Flies style in a bunker, and using mysteriously obtained T-rex urine for who-knows-what.

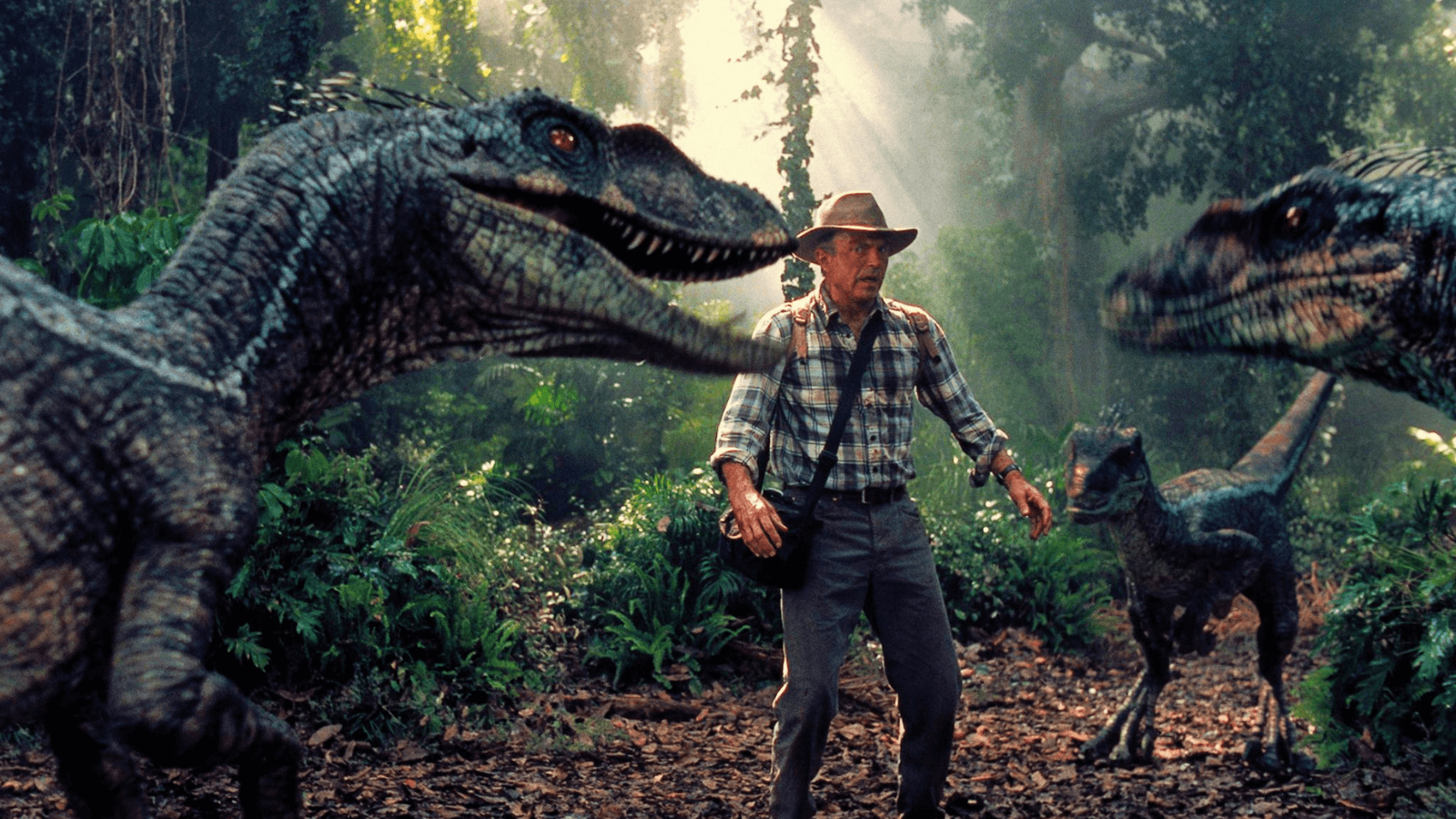

More than the preceding chapter, Jurassic Park III has several exciting sequences, thanks in large part to Johnston’s effective staging of the action and the committed performances by Neill, Macy, and Leoni. There’s a suspenseful gag about the Spinosaurus eating a satellite phone along with one of its victims, and the phone’s ringtone signaling its fearsome presence nearby. Another sequence takes us into Jurassic Park’s aviary, where a flock of flesh-eating Pteranodons soar in the mist. Technical adviser and paleontologist Jack Horner helped incorporate some fascinating and modern theories about Velociraptors, including new wiry feathers; although, once again, the film takes liberties with the intelligence and size of these beasts. Grant even suggests that, had dinosaurs survived all those millions of years ago, Velociraptors would have evolved into the dominant species on the planet. The story portrays them as protective, communicative parents, stalking Billy after he steals Velociraptor eggs from a nest. In a sense, the film is a long chase involving humans on the run from the pursuing Spinosaurus and Velociraptors. Unfortunately, the time in-between dinosaur attacks, while occasionally humorous, doesn’t allow for much in-depth character exploration.

Jurassic Park III is full of formulas and clichés, but the spectacle feels commonplace. Unnecessary characters are once again chased and eaten, and the essential characters get away in a last-minute rescue. We might not care at all, except Grant (and, on the margins, Ellie) creates a connection back to the original. Without that connection, watching the film might be completely hollow and superfluous. But there’s also more dinosaur action than its predecessors, so it’s at least modestly diverting, certainly more so than The Lost World. Johnston’s sequel keeps moving and keeps the audience munching popcorn, and it boasts the added benefit of dinosaurs that vary from earlier models—the Spinosaurus and Pteranodons make intimidating additions to the park’s animal roster. Still, the dinosaurs are treated like monsters here instead of awe-inspiring relics of Nature, all teeth and no wonder. When a Jurassic Park film barely stops to bask in the glory of these creatures, their singular and scientific marvel, it sacrifices spectacle for mindless chills and becomes more akin to the hackneyed dino-movies of yesteryear.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review