Jungle Cruise

By Brian Eggert |

Disney’s Jungle Cruise turns another theme park ride into a blockbuster. If you’ve experienced the ride, which helped launch the Anaheim, California, park in 1955, you’ll remember the guide’s groan-inducing puns, the hints of racism that casually romanticize colonialism (removed in 2021), and the occasional animatronic creature. It’s one of Disneyland’s lesser attractions, and they keep it around more out of tradition than entertainment value. For the movie, five credited screenwriters repeat the formula that made 2003’s initial Pirates of the Caribbean a success. Jungle Cruise attempts to balance old-fashioned adventure with supernatural flourishes, though fans will be hard-pressed to remember any mystical curses in the original Disneyland attraction. And in the truest Disney spirit of exploiting intellectual property to the fullest, the new movie serves its purpose, wrapping an escapist Amazonian yarn in a standard package lined with celebrities and spectacle, but not much else beneath the shiny veneer.

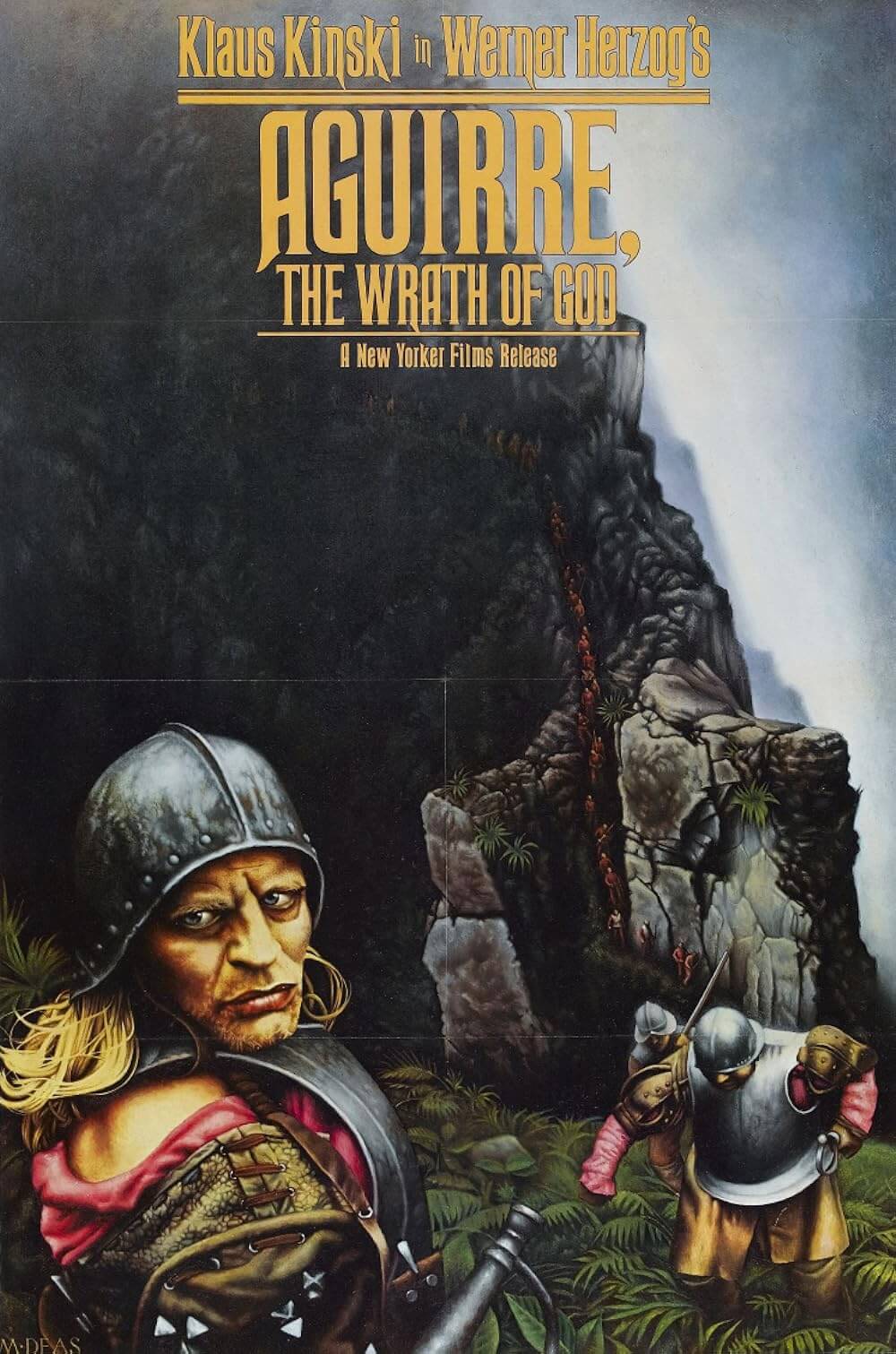

Even though she’s the movie’s hero, Emily Blunt receives second billing as Lily, a doctor of botany and member of British society. Unfortunately, her class means less than her gender to the male-dominated explorers’ club, which refuses to support her proposed expedition to the Amazon. Lily dreams of locating a magical tree of life, dubbed “Tears of the Moon,” which, legend has it, contains otherworldly healing powers. To find the tree, she must read the clues on an arrowhead artifact and follow one MacGuffin to locate another. Once paired with her mischievous riverboat captain, Frank (Dwayne Johnson), Lily and her fussy brother MacGregor (Jack Whitehall) head into the wild to face dangers from every angle. Besides the usual threats of piranha and big cats, Lily and company must contend with a German submarine headed by Jesse Plemons, who evokes Werner Herzog in his comical villain performance. Later, they must battle a Spanish ghoul named Aguirre (Edgar Ramírez) and his band of fellow conquistadors, each cursed by the jungle in a distinct way (snake-man, bee-man, tree-man, etc.)—in a manner clearly inspired by Davy Jones and his crew from Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006).

Herzog references aside, Jungle Cruise feels like a lame attempt to repeat what worked in other material, resulting in a patchwork of nods and influences. How fitting, since the original ride was inspired by Disney’s nature documentaries, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and the famous 1951 film The African Queen, starring Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart. The movie draws superficial inspiration from those sources as well—Johnson looks downright absurd as a musclebound version of Bogart’s lovable Charlie Allnut, and Frank would have been better suited to an actor capable of playing him roguishly. But Jungle Cruise is more interested in rehashing the mixture of archeology and fantasy from Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) with the comedic tenor of The Mummy (1999). It’s all energetically helmed by Jaume Collett-Serra. Still, its by-the-numbers script prevents the material from taking off, despite the occasionally inspired line reading from Plemons or an oddly innuendo-laden sequence that probably earned the movie its PG-13 rating.

At one point on the boat, Lily pulls out an early film camera, starts cranking to commit her journey to celluloid, and reflects on cinema’s rare ability to let you “experience anywhere in the world.” Walt Disney was enamored by the idea of showing his audience a slice of far-away places, so he created travelogues and short films so the average person could see distant lands. However, Jungle Cruise never transports the viewer to an exotic location outside of a VFX computer program. The production was filmed in Hawaii and on Atlanta soundstages, and every shot on the boat looks like Blunt and Johnson stood in front of green screens. The separation between the actors and the backdrop is a persistent digital layer, constantly reminding the viewer of the artifice at work. Additionally, the movie’s many attempts at revisionary political correctness—Lily’s role as a hero rather than damsel; MacGregor’s stereotypically represented gay character—feel undone when Frank hires his Indigenous friends to dress in “booga-booga costumes” and pretend to be headhunters.

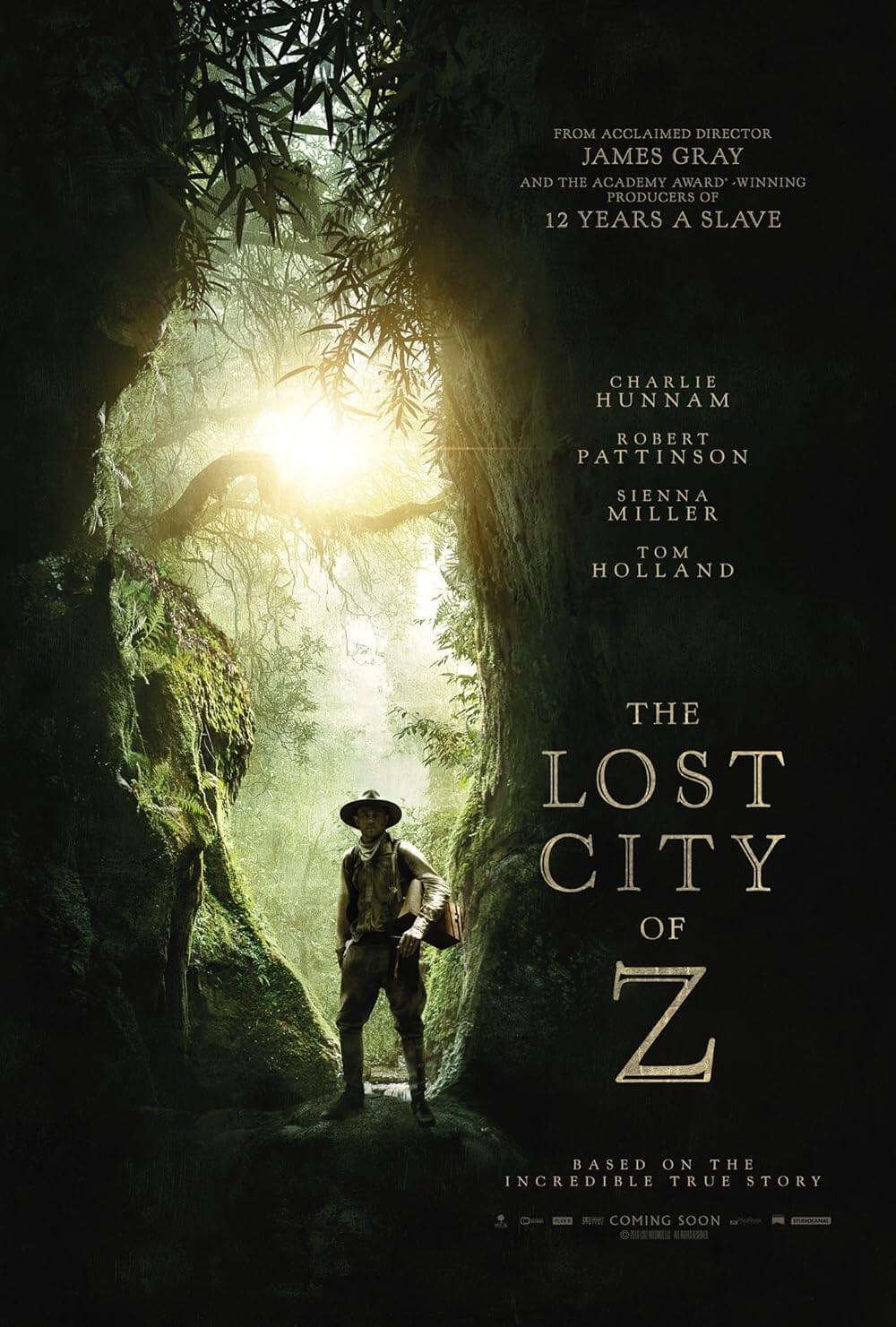

In Jungle Cruise’s final act, the oppressive spectacle and resulting CGI blindness turn the proceedings into a digital mess. What’s surprising is how awful most of it looks. Dead Man’s Chest came out 15 years ago, and the octopus-faced Davy Jones remains one of the great examples of CGI done right. By contrast, Aguirre and his shoddily assembled cohorts look like cheap knock-offs, accented by a score from James Newton Howard and Metallica (!) that lends a strange, incongruous heavy metal guitar to their scenes. Moreover, the entire movie would have been served better by a grounded narrative, like a playful version of James Gray’s The Lost City of Z (2016). As is, the movie proves difficult to enjoy as mindless escapism because it looks so unconvincing—not to mention the script’s boilerplate plotting, banal characters, and general second-hand quality. No amount of money, not even the reported $200 million budget, can help Jungle Cruise avoid tasting like a hunk of processed meat from the Disney conveyor belt.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review