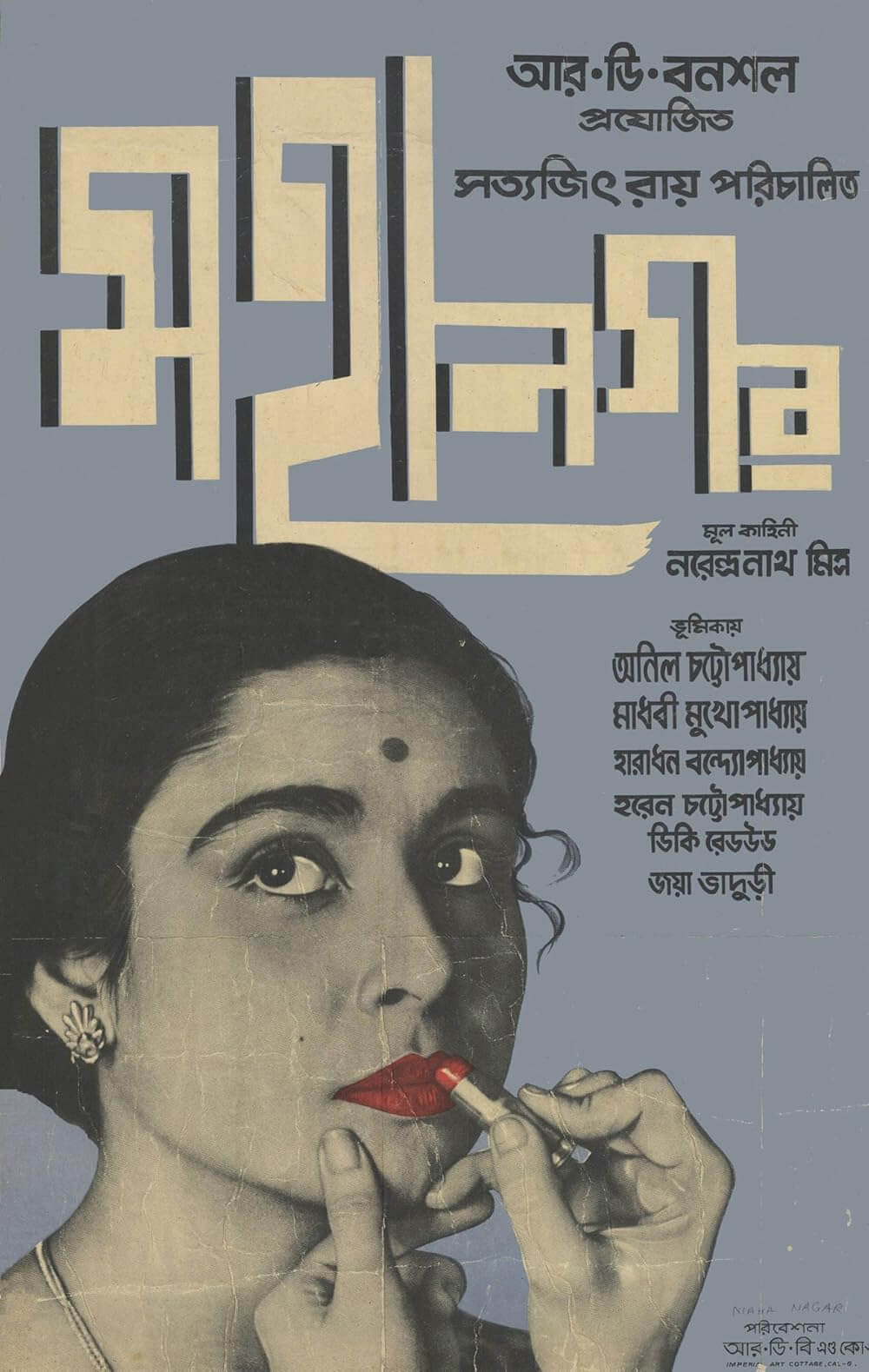

Judy & Punch

By Brian Eggert |

Punch and Judy puppet shows have entertained audiences for centuries with their brutal slapstick. In the usual performances, Punch, the armed and angry protagonist, batters anyone who crosses his path. Although his pile of victims starts with his wife, Judy, and their infant children, he’s also known for beating the constable who investigates the murders. He even kills a dog named Toby. Soon enough, one death leads to another, until he’s pummeling ghosts, sometimes Satan himself—all for the amusement of children (there’s nothing like mass murder to evoke the cheers and delight of youngsters). Australian actor-turned-director Mirrah Foulkes recognizes the oddity of this tradition, and her debut feature invents a strange origin story. Transformed into a thoroughly entertaining #MeToo era version with the reordered title to match, Judy & Punch may take place centuries ago, but its many anachronisms turn the toxic masculinity, Trumpian villain, and inevitable female empowerment into a decidedly modern commentary.

This topsy-turvy story takes place in Seaside, a British peasant village located far from the sea. It’s a town ruled by an intolerant mob of rustic, simple folk whose main pastime is stoning heretical women. And so, the locals are wildly entertained by puppeteers Punch (Damon Herriman) and Judy (Mia Wasikowska), who perform a full-stage domestic abuse marionette show that would be the envy of John Cusack in Being John Malkovich (1999). Although it’s the intelligent and capable Judy who brings artistry to their performances, Punch prefers to keep it “punchy and smashy” to appease his rowdy audience of drunken men and buxom women. He also takes the credit. Punch’s name appears more prominently on their posters, and being an unchecked narcissist, he responds to Judy’s pleas for artistic integrity like the nagging wife in their show. To be sure, Punch allows life to imitate art, and as he becomes increasingly drunk and violent, his behavior reflects his stage character. Before long, a horrible situation leaves Judy buried alive in a leafy grave in the woods (what happens to their child is best left unsaid), while Punch blames a kindly old couple (Terry Norris and Brenda Palmer) for the murders.

Here’s a film about an egomaniac who manipulates his audience by preying on their increasingly paranoid superstitions and prejudices. Elevated from a lowbrow showman to a community leader, he convinces his unwavering followers to do awful things simply by pointing a finger, making wild claims, and being the loudest voice. He thrives on their attention, as well as validation from the media. Herriman manages one of the more detestable roles in recent memory, despite playing Charles Manson, twice. Foulkes doesn’t need to spell it out further; her remarks about certain fascistic, showman political leaders are clear enough. Then again, the people of Seaside were awful before Punch arrived. They have a long history of frightening off anyone who doesn’t look or behave like everyone else. When Judy awakens, she finds herself in the care of several banished women who run a nomadic camp in the woods. Some have been accused of witchcraft; others simply look larger or smaller than average. Whatever the reason, they live like rogues in Sherwood Forest, and Judy soon becomes the Robin Hood who leads them out against the resident megalomaniac.

Judy & Punch’s modern-day parallels go beyond its political reflection of our times; Foulkes also employs a bizarre sense of humor that feels post-modern and ironic, if not referential at times. When Punch gives a speech to spectators of an execution, he quotes 2000’s Gladiator (“Father to a murdered son, husband to a murdered wife—I will have my vengeance, in this life or the next”), a moment Foulkes uses to demonstrate how he sees himself as the hero. After all, he’s been the central figure in a piece of children’s entertainment for hundreds of years, supplying an example that domestic violence and male aggression deserve applause. In any case, Foulkes saturates her film with period-inappropriate language and odd formal touches, lending the experience a wonderful comedic edge that embraces the story’s roots in escapism but also adds a touch of absurdity. For instance, the local bar goes by the name McDrinky’s, and there’s at least one death that is equally horrific and riotous.

Judy & Punch’s modern-day parallels go beyond its political reflection of our times; Foulkes also employs a bizarre sense of humor that feels post-modern and ironic, if not referential at times. When Punch gives a speech to spectators of an execution, he quotes 2000’s Gladiator (“Father to a murdered son, husband to a murdered wife—I will have my vengeance, in this life or the next”), a moment Foulkes uses to demonstrate how he sees himself as the hero. After all, he’s been the central figure in a piece of children’s entertainment for hundreds of years, supplying an example that domestic violence and male aggression deserve applause. In any case, Foulkes saturates her film with period-inappropriate language and odd formal touches, lending the experience a wonderful comedic edge that embraces the story’s roots in escapism but also adds a touch of absurdity. For instance, the local bar goes by the name McDrinky’s, and there’s at least one death that is equally horrific and riotous.

Far from historically accurate to any specific time and place, Judy & Punch takes playful artistic liberties in its mise-en-scène. François Tétaz’s music ranges from an electronic beat during the opening credits to a plucking, jolly tempo as things go disastrously wrong. Elsewhere, Foulkes uses a Leonard Coen song and some Bach to heighten scenes. The score recalls Michael Nyman and Damon Albarn’s strange yet amusing music for Ravenous (1999), which leaves the viewer unsure whether to laugh or gasp. Isn’t that how we’re supposed to feel watching Punch & Judy or Judy & Punch? Elsewhere, costume designer Edie Kurzer and production designer Josephine Ford create a rich assemblage of earth tones and crimson reds, which d.p. Stefan Duscio captures with textured digital detail. But a keen eye will notice flourishes that do not belong in this setting, intentionally so. And don’t bother trying to figure out how Judy accomplishes some of her acrobatic feats in the last-third, like a hooded figure out of Assassin’s Creed. It’s enough to know she has claimed a place as the hero of her story.

“You all live daily with the fear of your own difference,” proclaims Judy to a crowd of onlookers. Wasikowska, far better at giving speeches here than her appearances in Tim Burton’s awful Alice in Wonderland movies, makes a stirring feminist hero. She accomplished something similar in the underseen Damsel from 2018, where she played another kind of revisionist trope. And while Judy & Punch couldn’t be called subtle in its application of such contemporary rhetoric, it offers a necessary evaluation of a story whose venerable history remains troublesome. Foulkes uses the cinema as her modern puppet theater to identify patterns of violence against women, intolerant crowds, and self-obsessed leaders, and her debut questions them. She fashions a darkly funny film to entertain and comment, turning the tables on tradition in delightful and significant ways.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review