Judy Blume Forever

By Brian Eggert |

This film was screened at the 42nd Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival. For the full lineup of films available between April 13-27, check out the schedule here. The film arrives on Amazon Prime Video on Friday, April 21.

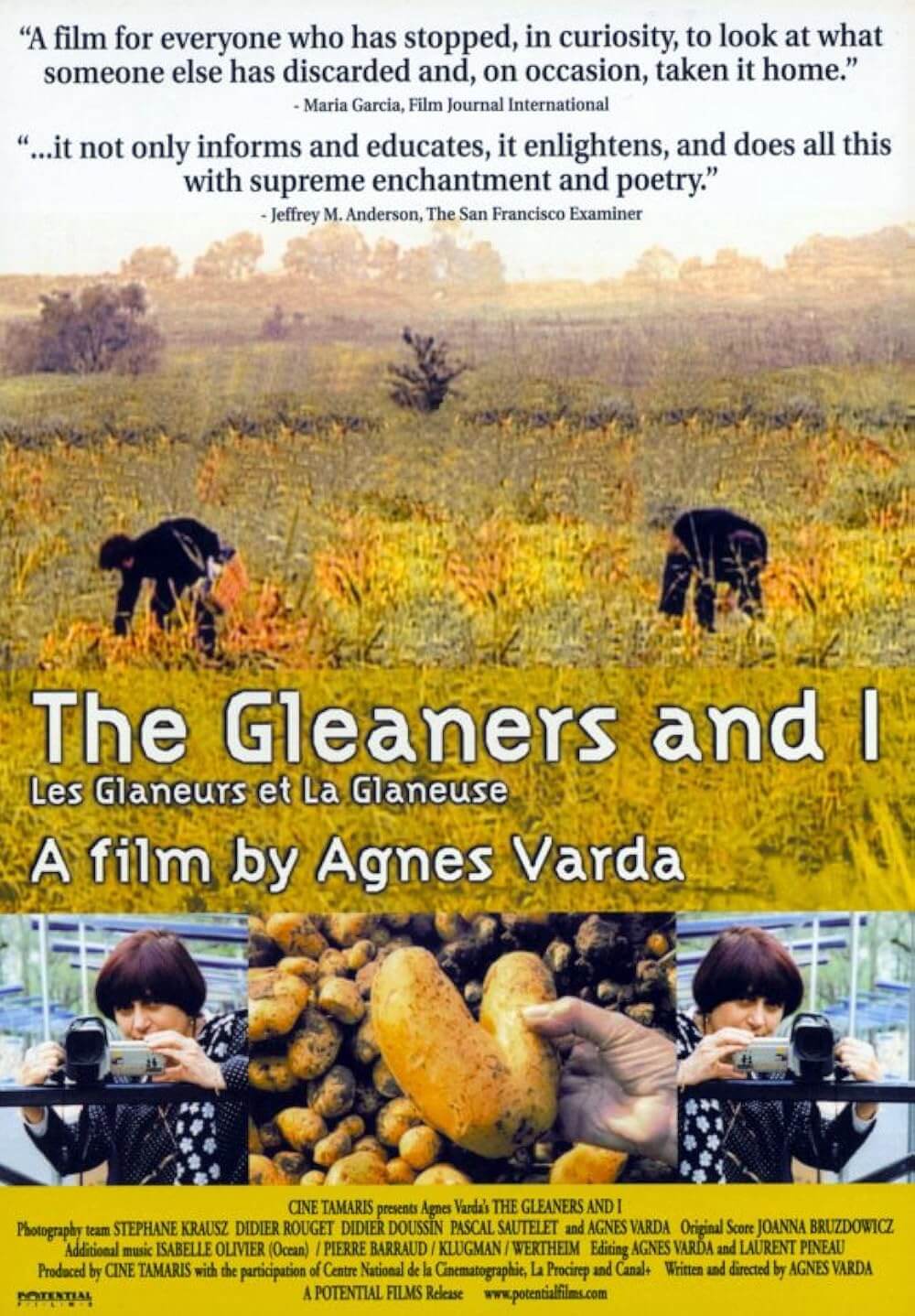

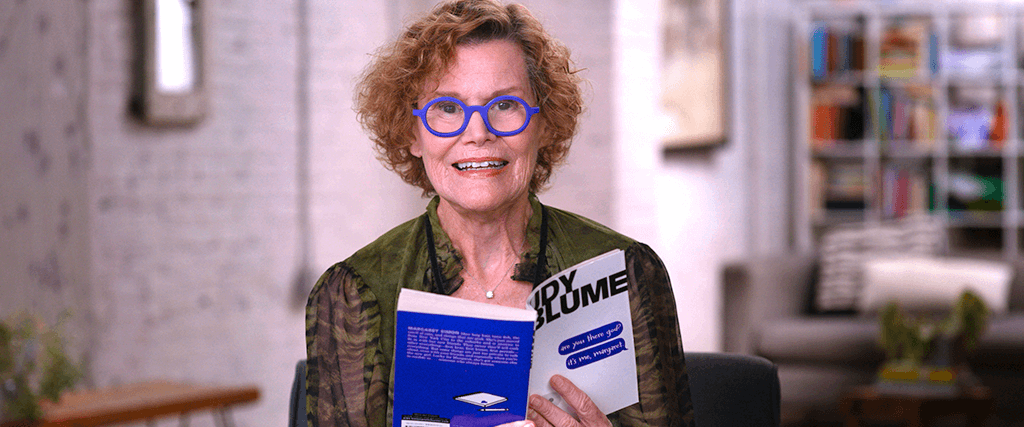

Judy Blume is unquestionably an icon with 80 million books sold over a career spanning five decades. Chances are, you read one of her books in your youth. And likely, it made you realize something about yourself, about your childhood, about your sexuality, or about your experiences growing up. She wrote characters that children could identify with, and by extension, she seemed to understand children better than their parents did. Judy Blume Forever is a documentary that celebrates her impact, looking at her progressive work and the broader discussion of Blume in American culture. Although her last book was published in 2015, and her most famous books were published in the 1970s and 1980s, she retains a lasting effect—to the extent that conservative groups are still trying to ban her books. Even so, her books continue to find young readers who recognize themselves in her characters, and they continue to prompt outrage and censorship for their honesty, despite how many children are positively affected. Told with admiration for its subject, the doc serves as a reminder of how essential her work remains.

Directed by Leah Wolchok and Davina Pardo, Judy Blume Forever adopts a boilerplate documentary format, blending talking head interviews with a scrapbook’s worth of archival photos, home videos, and Blume’s media appearances with the likes of Gene Shalit, David Letterman, Joan Rivers, and others. Famous children’s book authors, entertainers, publishers, and scholars of YA fiction speak in praise of her work and how it influenced them, with names like Samantha Bee, Molly Ringwald, Mary H.K. Choi, Jacqueline Woodson, and Lena Dunham among them. They read, affectionately, whole passages from her books, which the directors set against kaleidoscopic animated sequences that prove abstract and off-point. For example, when Blume reads the part from Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing (1972) where Fudge eats his older brother’s pet turtle, the animations show Fudge riding on a turtle under the sea for some reason. Aside from these flourishes, the filmmakers don’t stray from today’s bio-doc form. If the film’s execution presents no surprises, the subject matter makes what might be another flat piece that aggrandizes a notable figure into a genuinely pleasant watch.

After a brief thesis-statement montage that establishes the film’s themes—children’s book writer, nostalgic presence in many children’s lives, and “the most censored writer of children’s books”—the film leaps into Blume’s childhood in the 1950s, an era of pretending and conforming to social norms. With a domesticated mother and adventurous father, Blume learned that adults keep secrets from their kids, and she wanted to uncover them. But after college, she went from being her parents’ child to her first husband’s “little wife,” so she resolved to carve out something for herself while keeping up appearances as a housewife. While the Women’s Liberation movement was burning bras and protesting for safe abortion access, Blume, after a rocky start with “imitation Dr. Seuss” books, addressed taboo subjects—menstruation, religion, masturbation, sexual curiosity—in a relatable way, therein pioneering realistic children’s books and YA fiction. And though she became a published author, the other housewives in her suburban neighborhood wondered, “When are you going to write a real book?”

Blume recounts a highlight reel of her life, speaking with a sharp wit and easy humor about her ups and downs, divorces and mistakes, and personal awakenings, which are best discovered on your own. The most tender sequences involve the personal letters Blume’s readers have written to her over the years. Stored in a Yale archive, 50 years of letters reveal how young readers felt a connection with Blume. “How do you know all our little secrets?” wrote one child. Other letters share deep insecurities, curiosity, confessions of abuse, and family trauma—all with the same openness found in Blume’s writing. A few of her penpals continued to share correspondence with her throughout their youth and into adulthood, and they give interviews in the film, reading their letters and sharing their stories about what Blume’s responses mean to them.

Along the way, Wolchok and Pardo underscore the importance of and reaction to each of her books. Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret (1970) captured that awkward period when some of your friends were hitting puberty, but you weren’t. The empowerment message in Deenie (1973) went overlooked for its two sentences about masturbation. Blubber (1974) dealt with bullying before the topic earned campaigns against it. Forever… (1975) treated teen sex as though it wasn’t a crime against humanity but a natural stage in a person’s development. Yet, for all of Blume’s honesty, the religious right and reactionary parents tried to ban her books from libraries and keep young readers sheltered under the boom of Reagan-era conservatism. Alas, the wave of censorial fanaticism has once again hit America, leaving Blume’s body of work a target for self-important people who want to enforce their close-minded values onto the rest of the world and control what books other people’s children can access. But I digress.

Fortunately, perhaps as a response to the rise in censorship debates, there is a Blume renaissance at the moment. A week after Judy Blume Forever arrives on Amazon Prime Video, writer-director Kelly Fremon Craig will release a much-anticipated adaptation of Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. And producer Mara Brock Akil is reportedly developing a series based on Forever… for Netflix. No doubt, Wolchok and Pardo’s film will support interest in those projects. But, as with most documentaries in this format, the degree to which you enjoy the film depends on your affinity for the subject. If you know nothing about Judy Blume, the film offers a veritable Wikipedia page overview. If you love her books, it reminds you what you love about them. And though it’s a basic approach, the difference is that Blume is an earnest interviewee, speaking from 83 years of life experience from a place of honesty and openness, just like her fiction.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review