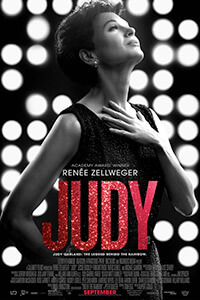

Judy

By Brian Eggert |

There’s a myth that Judy Garland’s death in 1969 incited the Stonewall riots in New York City, leading to that pivotal moment in gay rights activism. Long since debunked, the notion stems from Garland’s status in the LGBTQ circles at the time. She was a symbol in the gay community; her experience as a woman whose life was controlled by the spotlight, by Hollywood studios that regimented her every move, was relatable to people who also looked over the rainbow in hope of acceptance. Judy hit theaters on the 50-year anniversary of Stonewall, of Garland’s death, and of the birth of its star, Renée Zellweger. Based on the play End of the Rainbow by Peter Quilter, the film centers on the latter part of Garland’s life. The real story is much sadder, filled with suicide attempts and personal disasters—better captured by the 2001 ABC miniseries Life with Judy Garland: Me and My Shadows, starring Judy Davis—whereas Judy prefers to celebrate Garland’s life as a resounding triumph in spite of its obvious troubles.

Adapted by Tom Edge and directed by Rupert Goold, a longtime stage director whose only other feature film was 2015’s True Story, Judy adopts a familiar structure. It’s a biopic that brings scope to the life of its subject by focusing on a specific era. During Garland’s last year, she embarked on a five-week run of performances at London’s nightclub Talk of the Town. It was out of necessity. After losing a fortune, she could no longer afford to live in the U.S. or take care of her children, leading to a custody battle with her ex-husband, Sid Luft (Rufus Sewell). The film finds her ostensibly homeless, moving between intermittent venues, from one hotel to the next. It presents her time in London as a last hurrah, albeit marred by Garland’s dependence on drugs and alcohol, as well as her other addiction: husbands. While there, she marries her fifth beau, Mickey Deans (Finn Wittrock), a young man who looks at her dreamily, as if he’s marrying Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz. The public’s love of that film hangs over her head like a miasma.

The film’s nonlinear structure consists of banal flashbacks of Garland as a teenager (played by Darci Shaw), showing us the seed of her addiction, while they also halt the momentum of the more compelling 1960s scenes. Anyone vaguely familiar with Garland won’t be surprised when Louis B. Mayer (Richard Cordery) and his MGM cronies keep the young starlet in line by restricting her diet and creating her dependency on pills—a pill to suppress her hunger, a pill to keep her awake, and if those keep her from falling asleep, there’s a pill for that too. It leads to a lifelong complex, and being told what to do with her body by studio bosses, agents, and doctors becomes another kind of addiction. Even as an adult in London, she agrees to vitamin injections to amplify her performance; and in one sequence, she needs a club assistant (Jessie Buckley) to force her into the spotlight to overcome her pre-stage jitters. Being thrust, sometimes against her will, onto the stage is, tragically, how she operates best.

Judy restrains itself from depicting Garland at her worst; Goold omits many of the horror stories about self-mutilation, regular stomach pumpings, and the drug overdose that killed her at 47. It prefers to put a gloss on the bad times and celebrate the good, making what could be (and perhaps should be) a depressing profile into an aggrandizing tale of a beleaguered mother, victim of studio control, and legendary performer whose anxiety overcame her considerable talent. It’s a quirk of the film’s rosy retrospection that Zellweger is three years older than Garland when she died, but there’s no evidence of a lifetime of alcoholism, drug abuse, and depression on Zellweger’s face. Garland looked about 65 when she died (Time magazine reviewed the London performances and cruelly described Garland as a “walking casualty”). Zellweger appears comparatively youthful and vibrant, her performance filled with puckered lips and wide-open eyes, a combination of her own physical ticks and a so-so imitation of Garland’s. It’s a larger-than-life, showy performance, and Zellweger never disappears into the role, regardless of the excellent make-up, hairstyling, and costumes.

Judy restrains itself from depicting Garland at her worst; Goold omits many of the horror stories about self-mutilation, regular stomach pumpings, and the drug overdose that killed her at 47. It prefers to put a gloss on the bad times and celebrate the good, making what could be (and perhaps should be) a depressing profile into an aggrandizing tale of a beleaguered mother, victim of studio control, and legendary performer whose anxiety overcame her considerable talent. It’s a quirk of the film’s rosy retrospection that Zellweger is three years older than Garland when she died, but there’s no evidence of a lifetime of alcoholism, drug abuse, and depression on Zellweger’s face. Garland looked about 65 when she died (Time magazine reviewed the London performances and cruelly described Garland as a “walking casualty”). Zellweger appears comparatively youthful and vibrant, her performance filled with puckered lips and wide-open eyes, a combination of her own physical ticks and a so-so imitation of Garland’s. It’s a larger-than-life, showy performance, and Zellweger never disappears into the role, regardless of the excellent make-up, hairstyling, and costumes.

Unlike Davis’ take on Garland (which involved some convincing lip-syncing), Zelwegger performs the songs herself—a Best Of compilation including “The Trolley Song,” “Over the Rainbow,” and “Come Rain or Come Shine”—and her voice is perhaps more confident than Garland’s was at the time after a tracheotomy and other health issues. What Zelwegger captures well is the wired tension of a woman who, even with Mayer long since dead, still hesitates before biting into a piece of cake. Surely it’s a relatable character for Zelwegger, who stepped away from the spotlight for much of the 2010s after, according to interviews in recent years, Hollywood nearly broke her. Doubtless, women subject to scrutiny about their appearance and public image will find this material germane today. Still, the film prefers to relish Garland’s talent, which solidified her legacy, rather than admit how she was chewed up and spit out by the entertainment industry.

The setup recalls 2018’s Stan & Ollie, about Laurel and Hardy’s final music hall performances across the United Kingdom, which was a much better and appropriately bittersweet film. Given its ennobling treatment, Judy has drained the subject of much interest or engagement. It’s far more precious about its subject, and thus calibrated for mass appeal and nostalgia. Zelwegger’s performance remains the centerpiece of discussion about the film, which entices our fascination with actors’ ability to give an impression of other actors—but it’s an overwrought, Broadway-style turn, dialed up to eleven, and designed to please crowds and earn awards consideration (she won a Golden Globe and snagged an Oscar nomination). Accordingly, Goold and Edge end their film in a spot that makes Garland’s final performance look like a victory despite its grim reality. Similar to Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) and other musician biopics, Judy would rather pander to longtime fans by redirecting their attention away from the ugly truth, leaving viewers with a vague idea of her personal problems but no doubt of her talent.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review