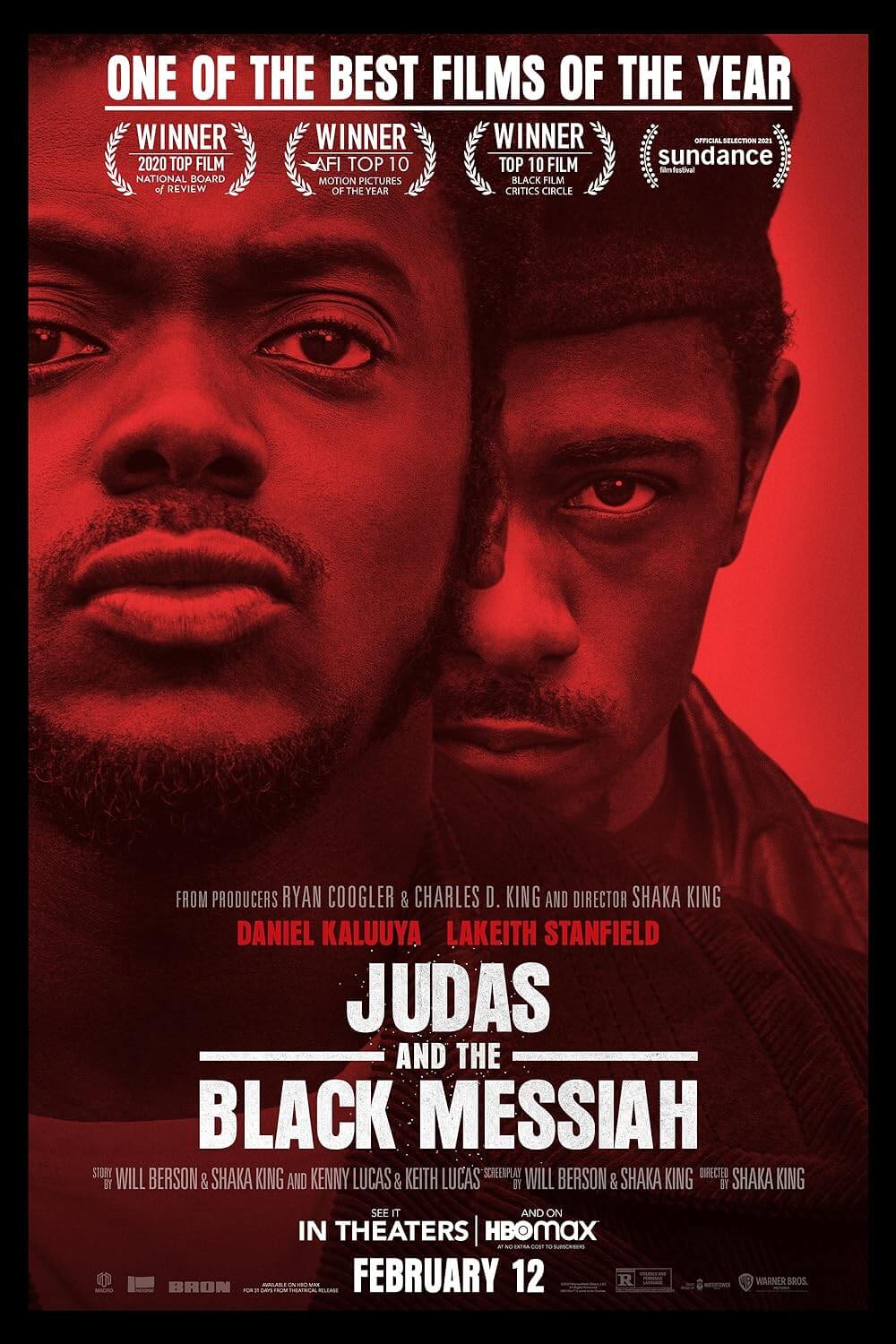

Judas and the Black Messiah

By Brian Eggert |

In 1969, the FBI raided the home of Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party and founder of Chicago’s Rainbow Coalition, a multicultural organization of marginalized communities assembled to combat poverty, police violence, hunger, and inadequate housing conditions. J. Edgar Hoover considered Hampton a threat to the white establishment and wanted to prevent him from becoming a “Black Messiah.” Using tactics established by the FBI’s counterintelligence program (dubbed COINTELPRO), Hoover’s agents planted an informant, William O’Neal, in Hampton’s chapter of the Black Panthers. O’Neal fed the FBI information over several months and, meanwhile, ascended to a position of authority in the Panthers’ ranks, even running Hampton’s security. O’Neal also gave the FBI the floor plan to Hampton’s apartment. And on the night of the FBI raid in December 1969, O’Neal drugged Hampton, making way for an execution-style assault that left several Panthers seriously injured by gunfire and Hampton dead at 21 years old. The police fired nearly 100 rounds in the exchange; the Panthers fired a single shot. It was an assassination.

Judas and the Black Messiah is the first dramatic feature to tell Hampton’s story, a subject covered in documentaries like The Murder of Fred Hampton (1971) and touched on in 2015’s The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. Directed and co-written by Shaka King, the production captures this disturbing, tragic, and all-too-relevant—and under-represented—chapter of American history for an audience that may be unfamiliar. At the center of the film’s narrative, conceived by Kenny and Keith Lucas, co-written by Will Berson, reside two complex portraits, each delivered by an actor in the prime of their talents: Daniel Kaluuya puts his proven charisma to work as Hampton, adding several pounds to his lean frame to look the part; he also captures the energetic spontaneity of Hampton’s public speeches to uncanny effect. Lakeith Stanfield lends his nervy energy to O’Neal, a character with good reason to feel paranoid and unsettled in every microscopic gesture. Their relationship recalls the one in Donnie Brasco (1997), where the subterfuge leads to a genuine friendship and alliance, deepening the inevitable pain of betrayal.

King opens the story in the late 1960s when O’Neal, then 17, carries a fake badge and dons a G-man getup in a ruse to steal cars. Picked up for impersonating a federal agent, he’s interviewed by the FBI’s Roy Mitchell, played by Jesse Plemons in a coolly detached and morally compartmentalized performance. Mitchell asks O’Neal how he felt about the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. O’Neal responds that he never really thought about it. Despite having no stake in the Civil Rights Movement, O’Neal recognizes that a badge is scarier than a gun in Black neighborhoods, hence his scheme—in other words, he understands the racial dynamics; he just doesn’t yet realize how much it matters. Before long, O’Neal finds himself on assignment for Mitchell, infiltrating Hampton’s chapter of the Black Panthers and learning their views. At first, he’s unaffected by their aspirational social and community programs to provide “land, bread, education, healthcare, justice, and peace” to Black people, and he balks at their policy of treating women as equals instead of objects. And while O’Neal walks the line between the FBI and the Panthers, he begins to feel fulfilled in his work for Hampton, even if his instinct for self-preservation means keeping Mitchell happy.

King and editor Kristan Sprague alternate their focus between O’Neal and Hampton, gradually revealing Hampton to be more than merely a boisterous speaker and important leader of people. We meet him first from O’Neal’s perspective, watching him teach classes, give speeches that promote neither violence nor nonviolence but resistance to fascism, and engage with the various ethnic groups in Chicago that soon join together to form the Rainbow Coalition. Gradually, King peers into Hampton’s inner life through his relationship with a speechwriter, Deborah Johnson (Dominique Fishback). The animated leader suddenly becomes shy, wise, and nuanced. It’s a brilliantly acted performance that not only convinces the audience, but it also convinces O’Neal—in a sharply crafted scene that finds O’Neal moved by Hampton’s “high on the people” speech, and Mitchell recognizes that O’Neal isn’t acting anymore. Fortunately, King and Berson’s script doesn’t manufacture dramatic scenes where these characters declare their feelings. Everything remains beneath the surface, relying on the actors to declare their character’s motivations with their eyes.

King and editor Kristan Sprague alternate their focus between O’Neal and Hampton, gradually revealing Hampton to be more than merely a boisterous speaker and important leader of people. We meet him first from O’Neal’s perspective, watching him teach classes, give speeches that promote neither violence nor nonviolence but resistance to fascism, and engage with the various ethnic groups in Chicago that soon join together to form the Rainbow Coalition. Gradually, King peers into Hampton’s inner life through his relationship with a speechwriter, Deborah Johnson (Dominique Fishback). The animated leader suddenly becomes shy, wise, and nuanced. It’s a brilliantly acted performance that not only convinces the audience, but it also convinces O’Neal—in a sharply crafted scene that finds O’Neal moved by Hampton’s “high on the people” speech, and Mitchell recognizes that O’Neal isn’t acting anymore. Fortunately, King and Berson’s script doesn’t manufacture dramatic scenes where these characters declare their feelings. Everything remains beneath the surface, relying on the actors to declare their character’s motivations with their eyes.

We also see increasingly tense meetings between Stanfield’s anxious O’Neal and his handler, or between Mitchell and his superiors, which reveal the ruthlessness and hypocrisy of Hoover’s FBI. Played by Martin Sheen under some unconvincing practical makeup, Hoover’s role is underdeveloped by design; the writers rely on his policies to drive the characterization. Hoover believes he’s fighting a race war, and his indoctrinated agents (mostly white men of a certain class and physical makeup) follow his every word and belief, often without question. Mitchell, too, parrots Hoover’s rhetoric, such as when he tells O’Neal that the Black Panthers are “no different than the Klan.” But when Hoover allows an informant to kill an innocent man to maintain his cover, it gives Mitchell pause in a scene beautifully acted by Plemons. You can see Mitchell negotiating whether to question the morality of the situation; though, he never raises the issue in any serious way. At that moment, we see how institutionalized racism and the FBI’s dirty pool were allowed to persist for so long. After all, most Americans supported Hoover’s tactics at the time, but historical evidence has eroded, if not entirely flipped his message that the Black Panthers were “terrorists” as Hoover claimed.

King’s second feature after 2013’s novice debut with Newlyweeds, a romance about a couple of stoners, Judas and the Black Messiah looks like the work of a seasoned professional. He draws from an array of ‘70s colors and textures, offering something reminiscent of a Sidney Lumet picture. The cinematography by Sean Bobbitt, a regular collaborator with Steve McQueen, is straightforward and functional, even while it cannot be described as devoid of style. The film has an immersive mise-en-scène that never calls attention to itself, offering long takes that place the viewer in a series of encounters—sometimes suffocating, such as when O’Neal must hot-wire a car at gunpoint to prove himself; sometimes intimate, as in the scene when Deborah wonders which force is greater, the pull of motherhood or the power of Hampton’s movement. These shots are just long enough to avoid falling into a self-indulgent aesthetic, yet they manage to feel more committed to their scenes than the average Hollywood production. Elsewhere, King offers a few sequences of violence that have been wonderfully, and hauntingly, orchestrated. The final scene of the police invading Hampton’s apartment is jarring beyond words. The music by Mark Isham and Craig Harris, too, is terrifically handled to offer notes of jazz, ‘70s funk, and at times a haunting sense of disorientation to reflect O’Neal’s internal division.

Judas and the Black Messiah considers some unsettling pages in history and inspires its audience to hunt for more like them. Hoover knew that merely imprisoning Hampton wouldn’t be enough to stop his message (he was sentenced to 2-5 years for allegedly stealing ice-cream)—prison is where revolutionaries solidify their ideas and publish them. Knowing the pen is mightier than the sword, Hoover fueled a conspiracy to assassinate Hampton before he could write down his ideas. More than just a murder, the film considers the emotional toll of what happened and why. A postscript shows us that, years later, during an interview with PBS for the documentary series Eyes on the Prize II, O’Neal claimed he didn’t have any allegiance to the Panthers. His interview aired on Martin Luther King Jr. Day Day in 1990. Later that day, O’Neal committed suicide by running into oncoming traffic. Stanfield plays O’Neal cagey and uncertain, torn between his need for survival and his newfound passion for the Black Panther Party’s idealistic cause. It’s a moral uncertainty that, apparently, ate away at O’Neal for years, and Stanfield captures that in his best performance to date.

Judas and the Black Messiah considers some unsettling pages in history and inspires its audience to hunt for more like them. Hoover knew that merely imprisoning Hampton wouldn’t be enough to stop his message (he was sentenced to 2-5 years for allegedly stealing ice-cream)—prison is where revolutionaries solidify their ideas and publish them. Knowing the pen is mightier than the sword, Hoover fueled a conspiracy to assassinate Hampton before he could write down his ideas. More than just a murder, the film considers the emotional toll of what happened and why. A postscript shows us that, years later, during an interview with PBS for the documentary series Eyes on the Prize II, O’Neal claimed he didn’t have any allegiance to the Panthers. His interview aired on Martin Luther King Jr. Day Day in 1990. Later that day, O’Neal committed suicide by running into oncoming traffic. Stanfield plays O’Neal cagey and uncertain, torn between his need for survival and his newfound passion for the Black Panther Party’s idealistic cause. It’s a moral uncertainty that, apparently, ate away at O’Neal for years, and Stanfield captures that in his best performance to date.

There’s a lot about Judas and the Black Messiah that defies Hollywood’s usual mode of none-too-radical Black stories designed to reach a wider demographic. Whether it’s stories about white people helping Black people (The Blind Side, The Help) or simply edgeless stories about Black history (Selma), we rarely see a major studio like Warner Bros. distribute a film like this into theaters (and HBOMax on the same day). The last film that felt steeped in the ideology of radical revolutionaries came in 1992 with Spike Lee’s Malcolm X, one of cinema’s greatest biopics. Fortunately, Judas and the Black Messiah arrives after 2020, a superb year for Black stories in film that includes Lee’s Da 5 Bloods, George C. Wolfe’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Sam Pollard’s documentary MLK/FBI, and Regina King’s One Night in Miami. King’s entry is among the best of these, offering equal measures of history and parallels to recent unrest in America. Since Fred Hampton isn’t a name found in the average American history book, Judas and the Black Messiah shines a light on a story that demands attention today, and it’s told with care and substance. With any luck, it inspires viewers to learn more about Hampton, COINTELPRO, and other accounts of powerful Black voices who spoke out and fought for a better life and, in some chilling cases, were silenced.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review