Joker: Folie à Deux

By Brian Eggert |

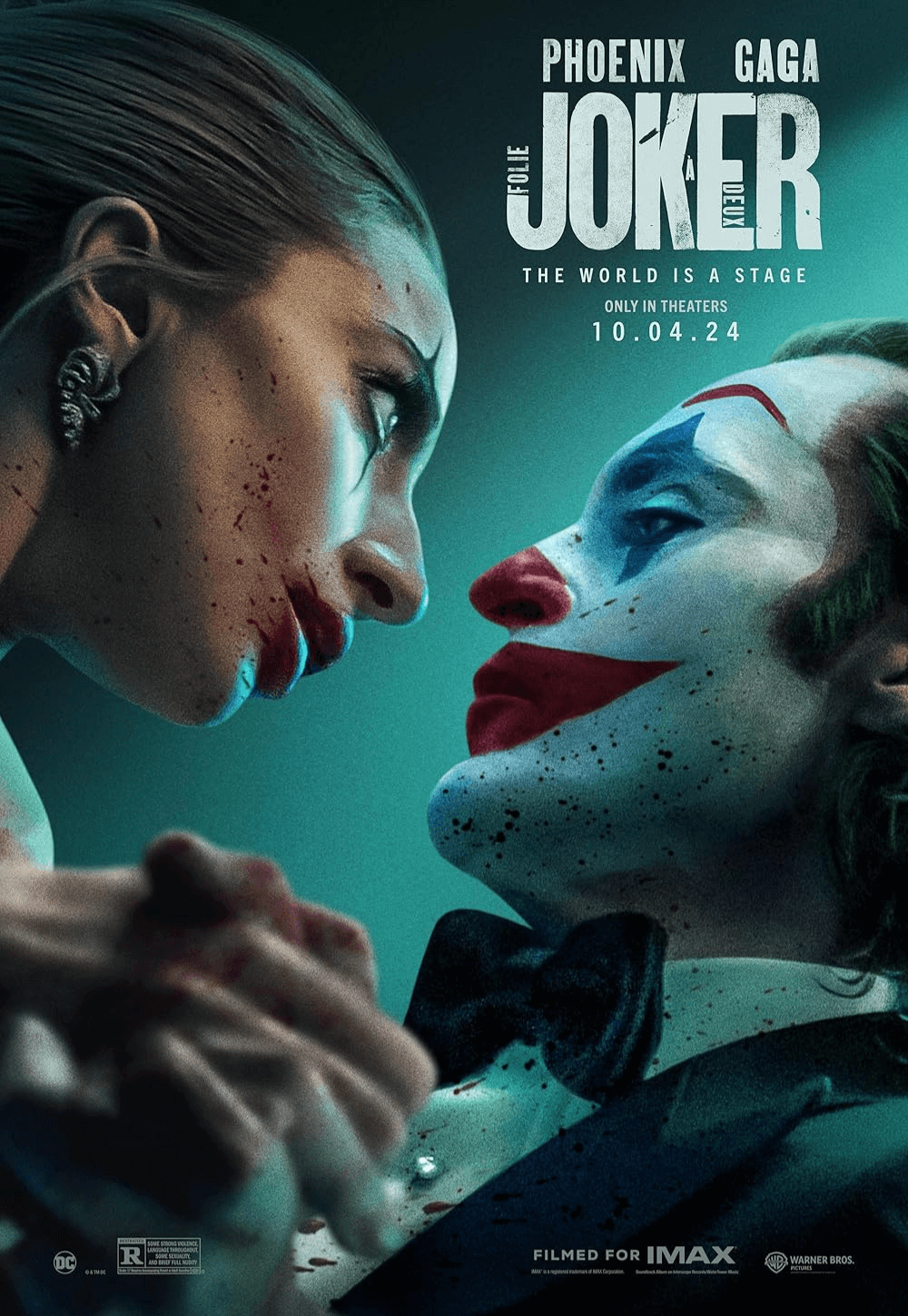

Joker: Folie à Deux is a lot of things. At its most basic, this is the sequel to co-writer and director Todd Phillips’ 2019 hit Joker, a gritty take on the Batman villain that earned over $1 billion in worldwide box-office receipts and caused a lot of heated debate about its intended meaning, assuming one exists. When Warner Bros. earned that much money on a reported $70 million budget, a follow-up was inevitable. And so, five years later, Phillips reteams with Joaquin Phoenix, who earned an Oscar for his sullen and unhinged performance, on a movie that’s part comic book, part musical, part courtroom drama, and part miserablist portrait of mental illness. Admittedly, I never quite settled on what its overrated predecessor hoped to be: A spotlight on America’s willingness to prop up a psychopath despite all evidence pointing to him being a narcissistic criminal? A condemnation of incels? A portrait of how people fall through the cracks of social systems? A superficial pastiche of ’70s cinema masquerading as an artistic supervillain origin story? A product of artistic self-indulgence? All of the above? None of these questions stuck with me because, a few days after reviewing Joker, it left no lasting impression apart from Phoenix’s performance. The same will likely be true of the sequel, a movie that takes a somewhat more stylistically bombastic way of telling a similar story of derangement and self-destruction.

Picking up a couple of years after Joker, the sequel finds Arthur Fleck (Phoenix) drained of all humor, lumbering along in prison like an empty shell of a person. Even the guards, headed by Brendan Gleeson, remark that the once high-spirited prisoner has become more morose than usual. Arthur faces a trial for killing five people, including a talk-show host (Robert De Niro) on live television. Central to his defense, which is mounted by his sympathetic attorney (Catherine Keener), is Arthur’s sanity and whether Joker was a split personality formed by Arthur’s mind to protect his vulnerable side from the harsh world. An aspiring creative mistreated by several systems (his mother, child services, the entertainment industry, the police, prisons, the courts, etc.), Arthur is presented as a victim, punished for not living up to the reputation that others assigned to him—loyal disciples who want Joker to lead a chaotic revolution. Never mind that Arthur is a murderer and stalker; it’s easier to put his crimes in a box and set them aside to consider his potential, which is both disturbing and disturbingly familiar.

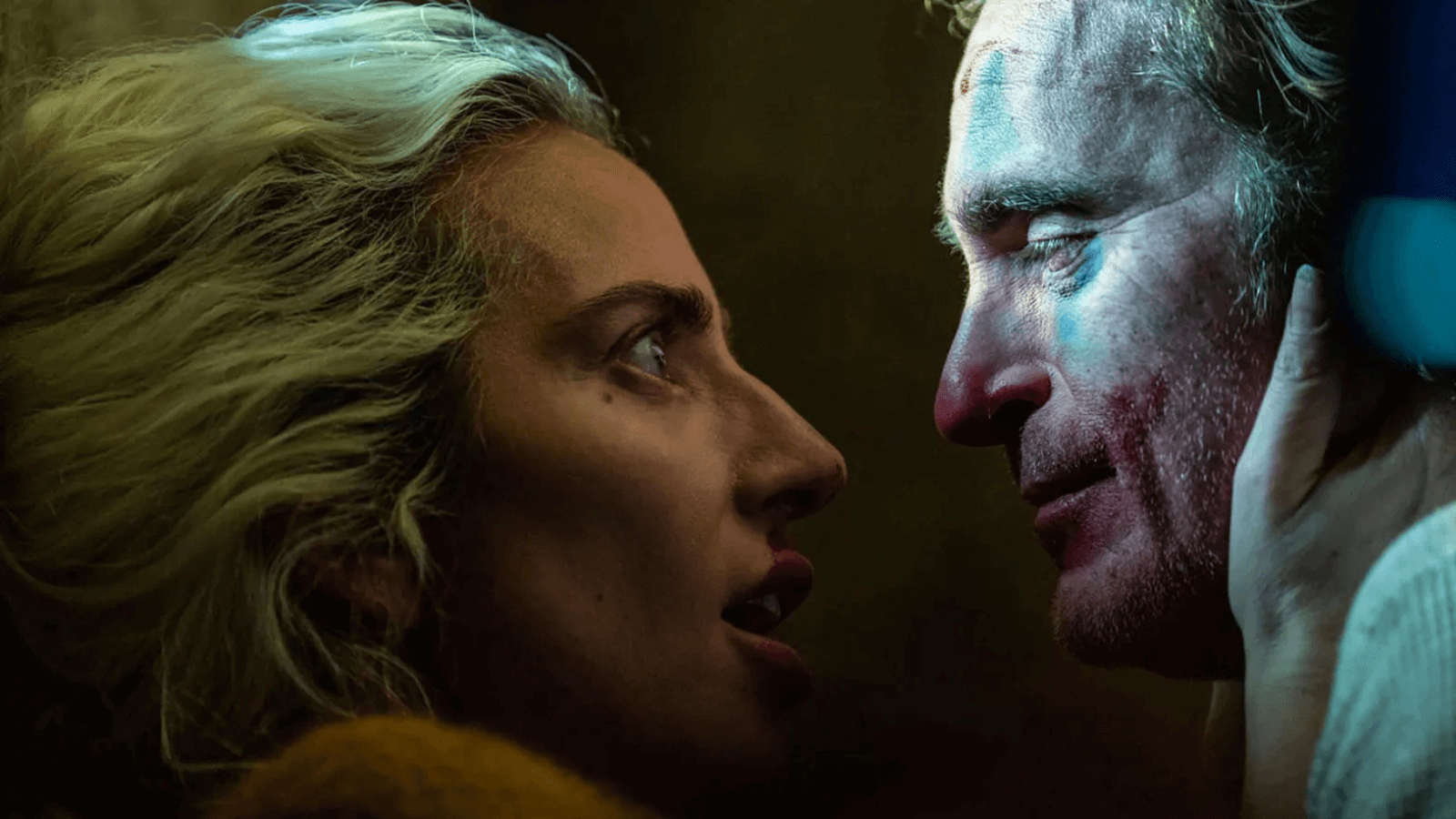

Among his loyalists is Harleen “Lee” Quinzel (Lady Gaga), an obsessive fan and enabler with whom Arthur bonds over their shared liking of the finger gun suicide gesture. Most of their falling-in-love moments unfold in dreamt-up musical numbers that might seem lavish to the mentally unsound, but not anyone versed in movie musicals—Phillips is not a director of musicals, and he makes that painstakingly clear. Lee quickly declares her love for Arthur and vows that they will “build a mountain from a little hill” and occupy a world of their own making. Meanwhile, Arthur fires his attorney in court and resolves to represent himself against prosecutor Harvey Dent (Harry Lawtey). The judge (Bill Smitrovich) warns the smirking Arthur not to make a mockery of his courtroom. The next day, Arthur shows up in clown makeup and puts on a Southern accent worthy of a John Grisham character. The judge allows it. Much like the whole film, the courtroom scenes exist to perpetuate themselves, building toward an explosive climax, followed by a whimper.

All the while, Phillips never takes us inside Arthur’s head like, say, Travis Bickle’s journals do in Taxi Driver (1976). Sure, we see Arthur’s delusional musical number sequences, apparently implanted in Arthur by Gleeson’s character, whose affinity for music and singing therapy proves contagious. After his penchant for stand-up comedy in response to a late-night TV show in Joker, it becomes clear that Arthur absorbs his surroundings and reflects them, albeit darkly. This time, it happens to be music that consumes him. But it could have been breakdancing, painting, or any number of activities that caused Arthur to fixate, had those been present in the movie instead. To that end, Arthur never feels like a tragic figure, just a cipher—a zero waiting to be filled by something, whatever’s in front of him. He’s unlikable, unsympathetic, and, based on all available evidence, hopelessly driven to self-destruction. The movie doesn’t present him in such a way that would produce empathy or understanding from the viewer; Phillips and co-writer Scott Silver present Arthur like a case study in mental illness, except the subject enjoys his particular malady. He latches onto Lee not out of deep love but because she worships the afflicted Arthur and confirms his worldview.

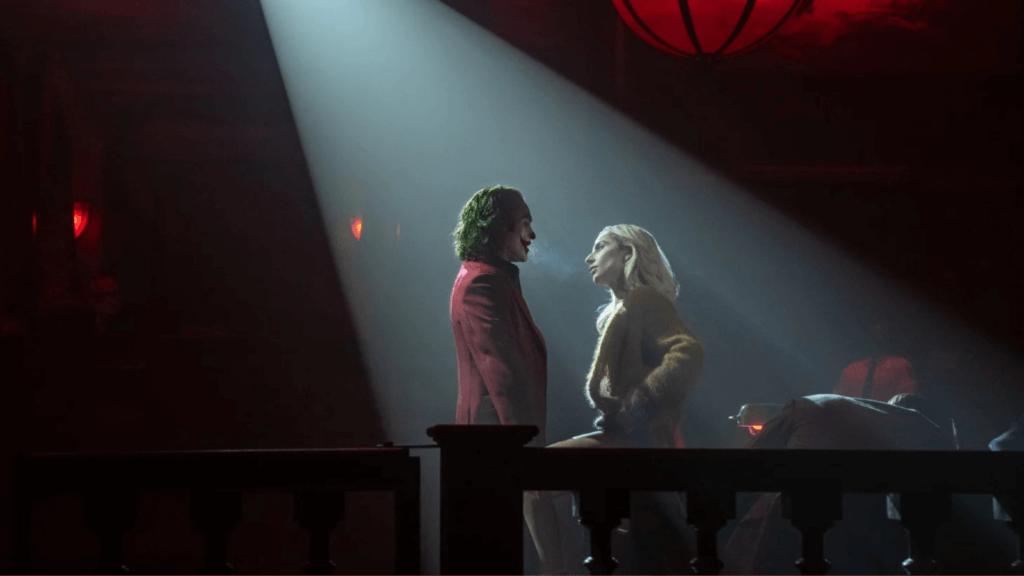

Phillips’ choice to rethink Joker as a musical is an anti-commercial statement, practically guaranteed to annoy the core film bro fanbase who championed the first one. In a way, it’s admirable to deny your audience what they want. But it’s also rather childish and Arthur-like. But perhaps Phillips’ rebellious streak didn’t motivate his decision to make Joker: Folie à Deux a musical at all. Maybe he just wanted to try something different and sought to emulate the musicals of French director Jacques Demy, such as The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967) or Donkey Skin (1970). Demy’s tendency to inject macabre details into an otherwise pastel-colored musical certainly feels like an inspiration here, albeit without the whimsy. At random, song-and-dance sequences burst into Arthur’s daydreams and hallucinations, breaking up the film’s otherwise oppressive monotony. Songs and Broadway standards from “When You’re Smiling” to “That’s Entertainment” to “That’s Life” feature heavily alongside a few uninspired original compositions. As a comic book movie, it’s not a very good one. As a musical, it’s even worse. The courtroom drama material falls flat as well, leaving the viewer almost nothing to grab onto, narratively.

This is all quite frustrating because Phillips has applied an unmistakable sense of craft. The movie opens with an inspired Looney Tunes-style cartoon called “Me and My Shadow,” featuring Arthur’s shadow self wrestling with him over stage time. Formally, the rest is competent. The dark-for-dark’s-sake cinematography by Lawrence Sher resists the allusionism of Joker, which relied heavily on Martin Scorsese’s early work for its look, feel, and themes. But it must be said that Phillips, Sher, and editor Jeff Groth put together a capable-looking picture. In the era of clunky blockbusters, that’s something. Even so, the musical numbers don’t inspire or invite admiration, even from a place of distanced appreciation for the skill involved. It doesn’t pop, shimmer, or shine, and its persistent grime isn’t the seedily effective sort found in Scorsese’s New York stories or David Fincher’s Se7en (1995). Underneath the visuals, Hildur Guðnadóttir’s brooding score emphasizes the mounting danger of every scene, but that feeling goes nowhere.

Without the fresh novelty of Phoenix’s portrayal of the Joker, spending time with his character becomes a tiresome, tedious experience. Although Phoenix’s uncanny performance may have been vital in the earlier film, he’s doing more of the same here, not taking the character to new heights. To be sure, I never believed Phoenix’s character, nor did the actor or the writing give me cause to care about him. The same is true of Lee—a far cry from earlier iterations of Harley Quinn—whose motivations prove superficial at best. Like Arthur, she’s an angry, petulant child, lashing out at the world. The sequel implants some doubt about Lee, who voluntarily checked herself into an institution and lied about her backstory to get closer to Arthur. Is she another of his many Manson Family-esque acolytes, or do they have a genuine bond? Will any of this matter to the viewer? At about the midpoint, Lee tells Arthur she’s pregnant, but nothing comes of this news. Maybe their child will grow up to become the real Joker who fights Batman. Then again, it’s impossible to know if Lee is lying to him about the child, as she does about so many other details, or if this might be true.

Joker: Folie à Deux feels like a project that exists because of a financial imperative, not an artistic one. It doesn’t say anything substantive or present its message in a subversive way. It does not break the rules, challenge limits, or push the boundaries of cinematic art or entertainment. When it’s all over, the ending arrives with a deafening thud, conjuring neither admiration nor hatred toward the result. It’s worse than something that offends or leaves you angry: it manages to produce no emotional reaction whatsoever and, moreover, happens to be quite a bore. The film failed to engage me with the story or make me care about where the characters would end up. In the end, I kept asking myself what Phillips and company sought to accomplish, what lesson they hoped to impart, or what they wanted the audience to take away from the experience. One could come up with myriad answers to these questions, none particularly satisfying or sufficiently communicated by the film.

If I had to assign some meaning, the timing of Joker: Folie à Deux a month before the U.S. presidential election suggests that Phillips warns against projecting meaning onto unbalanced and self-obsessed individuals who have no place in roles of authority. But that’s hardly what this critic came away thinking about. Overlong and repetitive, the film attempts to create dramatic contrasts by combining the usually light and airy musical genre with the grimy Gotham City found in Joker. Disparities and juxtapositions often result in dynamic works of art. Sometimes, you can combine unlikely ingredients and create an inspired concoction, offering new sensations and possibilities. Or you might wince and want to pour the result down the sink after one taste, vowing never to attempt that again. I remember once my wife tried to use pickle juice in a martini invention, and it didn’t work out. I thought of her disgusted expression while watching Folie à Deux.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review