Joker

By Brian Eggert |

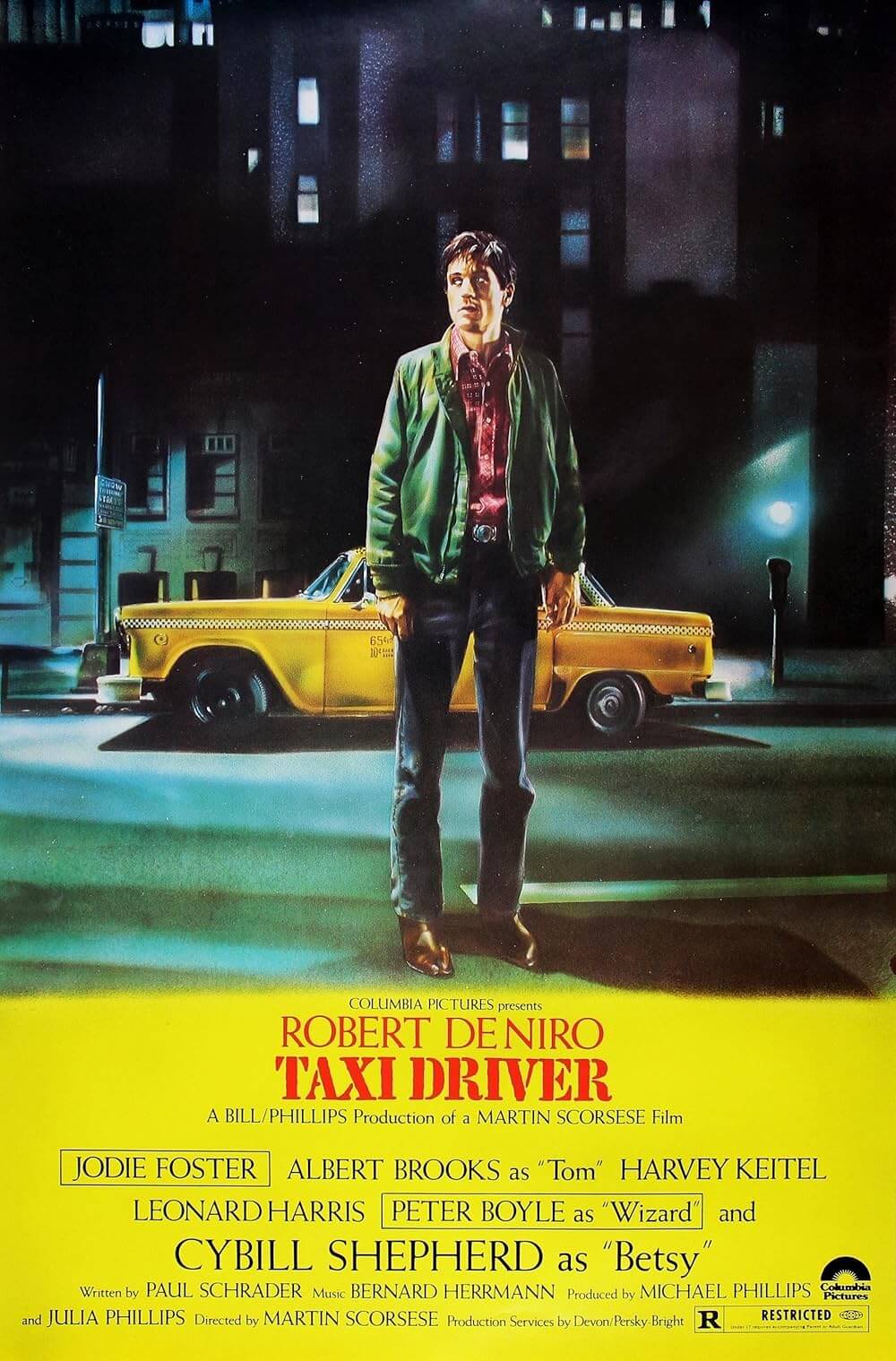

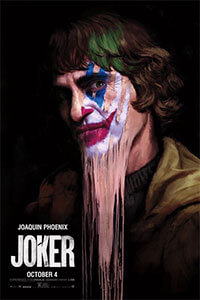

Miserable and nihilistic, Joker rethinks the iconic Batman villain in terms of a darkly realistic origin story of a murderer. Director Todd Phillips constructs a new version of the Joker whose emergence is preceded by textbook warning signs, including child abuse, an unstable family life, antisocial behavior, and various neuroses. It’s an unusual approach for a character whose chaotic behavior often proves entertaining only because Batman’s order balances it. The character, named Arthur Fleck and played in an uncanny performance by Joaquin Phoenix, lives in a seedier, punishing version of Gotham City, where he feels persecuted by society at large. Following the trajectory of another cinematic psycho, Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver (1976), Arthur finally lashes out at the world that has ignored and abused him, becoming a more disturbed and lower-stakes version of the legendary DC Comics villain. The film might be a reckless and angry statement about the world today, capable, although not intentionally so, of inciting incels to violence. It might be nothing more than a bleak character study in the footsteps of Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, commanded by an impressive performance and incredible formal craftsmanship, in which case it’s a bold piece of studio filmmaking. But Joker’s desperate need for subversiveness results in a confused portrait of a deranged bad guy, even as it strives for ambiguity. The film leaves the audience to question whether they should cheer for or feel disturbed by its central character. But it’s less a genuinely transgressive approach than one closely modeled on the work of Martin Scorsese, and thus more an exercise in homage than rebellion. Even so, that won’t stop people from aggrandizing it.

Late in the film, the camera glances up at a movie theater marquee—one of the few not showcasing a porno with the name of a Billy Wilder film—advertising Brian De Palma’s Blow Out and Peter Medak’s Zorro: The Gay Blade, dating the film to 1981. The setting is Gotham, whose real-life counterpart has always been New York, which in that same year had a garbage strike, over 2,000 homicides, and over 5,000 rapes. Accordingly, Gotham’s streets are littered with garbage, rampant crime, and newscasters warn of an increasing “super rat” problem (don’t bother inquiring because the film never explains). “Is it just me,” Arthur says, “or is it getting crazier out there?” Cinephiles will recognize the milieu, the urban sprawl of Scorsese’s elusive Taxi Driver, where human scum festers and the only source of brightness exists in the delusions of the protagonist. Along with several nods and even lines of dialogue pulled from The King of Comedy (1983), Phillips draws from Scorsese’s wellspring of New York stories about psychopaths who, upon being rejected by the world and those they admire, lash out in criminal ways that gain them the attention they need. But unlike De Palma, whose Blow Out paid homage by advancing the cinematic language developed by Alfred Hitchcock, Phillips’ brand of reverence uses his inspiration like carbon paper instead of a launchpad. Joker copies Scorsese’s aesthetic and themes, but it does not progress them.

Indeed, Phillips doesn’t shy away from citing his sources onscreen, and so Joker plays like the product of a talented filmmaker who spent his youth watching and rewatching Scorsese’s body of work. “Someday,” he said to himself, “I’m going to make a movie like that.” And that’s just what Phillips has done, without elevating what Scorsese was trying to say in his grittier 1970s and 1980s output. To be fair, Phillips has made an excellent piece of homage; it’s beautifully shot by d.p. Lawrence Sher, and the period details are nothing short of convincing. But Phillips folds themes from Scorsese into an established intellectual property for a pastiche taffy of cute references and respectful nods. It feels no more thoughtful or ambiguous than Phillips’ previous work, a series of films about immature men caught in a perpetual state of arrested development, from Old School (2003) to three Hangover movies. Lowbrow comedies have been his bread and butter since 2000’s Road Trip, but after producing last year’s A Star is Born and earning some clout with Warner Bros., Phillips has set his sights on something more ambitious. He seems to want to deepen established characters and give them some human dimension, something even darker than The Dark Knight (2008). However, all he’s done is demystify the myth; he’s turned an insane agent of chaos into John Wayne Gacy’s Pogo the Clown.

Phoenix’s Arthur Fleck lives in a grungy apartment with his mother, Penny (Frances Conroy), who he cares for and dotes upon. He works a thankless job as a clown, aspires to become a stand-up comedian, and occasionally stalks his neighbor (Zazie Beetz), with whom he’s infatuated. But the world has nothing except a long coil of excrement to pinch off on Arthur’s face. Within the first half-hour of Joker, Arthur receives not one but two violent beatings, loses his job, and endures no end of insults and rejections. The second beating, which takes place after a coworker has given him a firearm, results in Arthur shooting down three rich assholes employed by Thomas Wayne (Brett Cullen). Curiously enough, Arthur’s mother often refers to her glory days long ago as an employee of Gotham’s wealthiest patron, who is also a mayoral candidate. “Those of us who have made something of our lives,” Wayne says on live television, “will always look at those who haven’t and see nothing but clowns.” It’s a remark that incites outrage among the lower classes and builds Arthur, the anonymous clown killer, into a figurehead. After Arthur commits murder (in a sequence recalling The French Connection, again demonstrating Phillips’ affection for New York cinema of the 1970s), an act for which he has no regret, he inadvertently incites a movement, wherein the rich become targets for the repressed and dejected masses—all of whom don clown masks in honor of their perceived liberator.

The screenplay by Phillips and Scott Silver leaves a meandering breadcrumb trail to Arthur’s mental state. He was institutionalized and now sees a social worker (Sharon Washington) about his mental health. He takes seven prescriptions to keep himself sane. He has a neurological disorder that causes him to laugh-cry when under pressure, resulting in pained cackles and burps that announce themselves like Tourette’s syndrome tics. The specifics of Arthur’s mental condition prove less significant than how they are portrayed. If Joker has little to say outside of reactionary social politics and Scorsese-brand aesthetics, it’s an astounding vehicle for Phoenix’s talent. The actor somehow makes the film urgently compelling, and his body is so wincingly skinny—a quality that Phillips seems to savor in those shots where Phoenix raises his arms to reveal a sunken stomach, protruding ribs, and virtually no muscle mass. The transformation is incredible, and Phoenix’s ability to inhabit a character gives way to scenes of scary, internalized emotion on Arthur’s face—a lightning storm of conflicting expressions, from tears to riotous laughter, all about to burst from the inside of Arthur’s skeletal frame.

As the film carries on, Arthur’s history and psyche become more critical to the plot, which relies on a series of eye-rolling twists to propel Arthur over sanity’s edge. In a clumsy, Fight Club-esque moment, one character is revealed to be a figment of Arthur’s imagination, and therein, a sign of his growing insanity. He later discovers that his lineage is not what he thought it to be. Catalyst after wretched catalyst builds until, with about 20 minutes left in its two-hour runtime, Joker turns what has become a miserablist experience into a revenge story propelled by insanity. After all, Arthur’s few moments of violence have earned him media attention and followers, including crowds of clown-masked devotees willing to overwhelm, and presumably kill, a cop (Shea Whigham) who accidentally shoots a civilian. Finally, Murray Franklin (Robert De Niro), the host of a late-night talk show and Arthur’s idol, invites Arthur onto his program to be humiliated—after some video of Arthur’s embarrassing stand-up footage turns him into a laughing stock. It’s the last-ditch moment for Arthur to become Joker, and it’s the most ill-conceived scene in the film.

Watching Joker, one cannot help but think of Rob Zombie’s take on Halloween from 2007, a horror film that sought to unmask Michael Myers by constructing an elaborate backstory filled with child abuse and tortured animals. Thus, the mythological “Shape” from John Carpenter’s 1979 slasher became nothing more than another in a long line of Zombie’s serial-killer-obsessed gorefests. Something similar happens in Joker, where Phillips seeks to fill in the blanks of the character’s storied history. Famously, Heath Ledger’s rendition of the character spun a unique origin story for everyone he met, which left his past a mystery and rendered his version an unknowable force of energy. Phillips provides an alternative approach, as every fiber of Arthur’s being takes him further down the spiral toward the moment when he becomes that familiar face from Batman comics, cartoons, and movies. And yet, Phoenix’s take on the character never feels like someone who will develop into the Clown Prince of Crime; he’s not a criminal mastermind nor even particularly bright. Arthur makes impulsive decisions and spends most of the film getting abused and humiliated, and then having a violent reaction. In other words, there’s little evidence to suggest Arthur Fleck will ever concoct an elaborate plan that puts him five steps ahead of Batman. It’s more likely that he’ll just stab or shoot someone he resents.

Watching Joker, one cannot help but think of Rob Zombie’s take on Halloween from 2007, a horror film that sought to unmask Michael Myers by constructing an elaborate backstory filled with child abuse and tortured animals. Thus, the mythological “Shape” from John Carpenter’s 1979 slasher became nothing more than another in a long line of Zombie’s serial-killer-obsessed gorefests. Something similar happens in Joker, where Phillips seeks to fill in the blanks of the character’s storied history. Famously, Heath Ledger’s rendition of the character spun a unique origin story for everyone he met, which left his past a mystery and rendered his version an unknowable force of energy. Phillips provides an alternative approach, as every fiber of Arthur’s being takes him further down the spiral toward the moment when he becomes that familiar face from Batman comics, cartoons, and movies. And yet, Phoenix’s take on the character never feels like someone who will develop into the Clown Prince of Crime; he’s not a criminal mastermind nor even particularly bright. Arthur makes impulsive decisions and spends most of the film getting abused and humiliated, and then having a violent reaction. In other words, there’s little evidence to suggest Arthur Fleck will ever concoct an elaborate plan that puts him five steps ahead of Batman. It’s more likely that he’ll just stab or shoot someone he resents.

In a way, Joker being modeled after a crazed mass murderer is scarier because it follows the logic of a school shooter or someone with a sniper rifle in a bell tower. In another way, it’s lazier, as though Phillips couldn’t conceive of an intelligent person who transforms into an unhinged supervillain. Instead, Arthur behaves like a disgruntled, lonely person who tells an obvious window-into-my-soul joke: “What do you get when you cross a crazy person with a society that abandons him and treats him like trash?” The punchline is an act of public violence, a moment that, when seen by the deserted and unhinged, will feel cathartic. Dramatically, Phillips has engineered our empathy for Arthur. We find him at once worthy of our pity and yet his actions are detestable, making his final outburst an insane, murderous victory over those who wronged him. It’s a moment that is exhilarating and maybe even irresponsible. At the same time, the material leaves illogical leaps between the character as Phillips has made him and the requirements of a major motion picture about a famous intellectual property. Why, for instance, would a crowd of hundreds suddenly don masks and praise a madman who performs a violent act? A few handfuls of disturbed individuals devoted to a cult leader, that is believable. But hundreds of masked people suddenly driven to worship Joker like a god? It might seem implausible, except when you consider that people today worship a man with an orange mask and absurd hair despite his crimes (and so perhaps it’s not so unreasonable).

The controversy surrounding Joker—the worry that the film will incite real-life followers reminiscent of James Holmes—feels over-estimated, if not engineered as a promotional device to manufacture interest. Then again, people will doubtless cling to a film that dramatizes a “Kill the Rich” movement, not because Joker commands them to but because people can be insane. To be sure, certain aspects of the film exist as a mirror of American culture; however, Phillips jams that mirror in our face with an unsubtle hand. By the time Arthur first dons full Joker garb and dances down a long stairway, which before he only ascended at the end of each day as a symbol of his Sisyphus-like slog through life, Phillips resorts to an odd musical queue: Gary Glitters’ “Hey” song, music often played at sporting events. It’s a moment that feels obvious and pandering, just as his Scorsese references are—everything from De Niro’s presence to the recurring image of pantomimed gunshots to the temple from Taxi Driver. Joker might be an entirely thankless and dramatically unrewarding experience without Phoenix’s presence, whose sheer talent allows the viewer to endure the proceedings, smiling through the pain as its main character does, if only for the pleasure of watching this actor do his thing with unwavering commitment. The rest is just poking and prodding to garner a reaction, and mistaking such provocations for having something profound or meaningful to say.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review