Jojo Rabbit

By Brian Eggert |

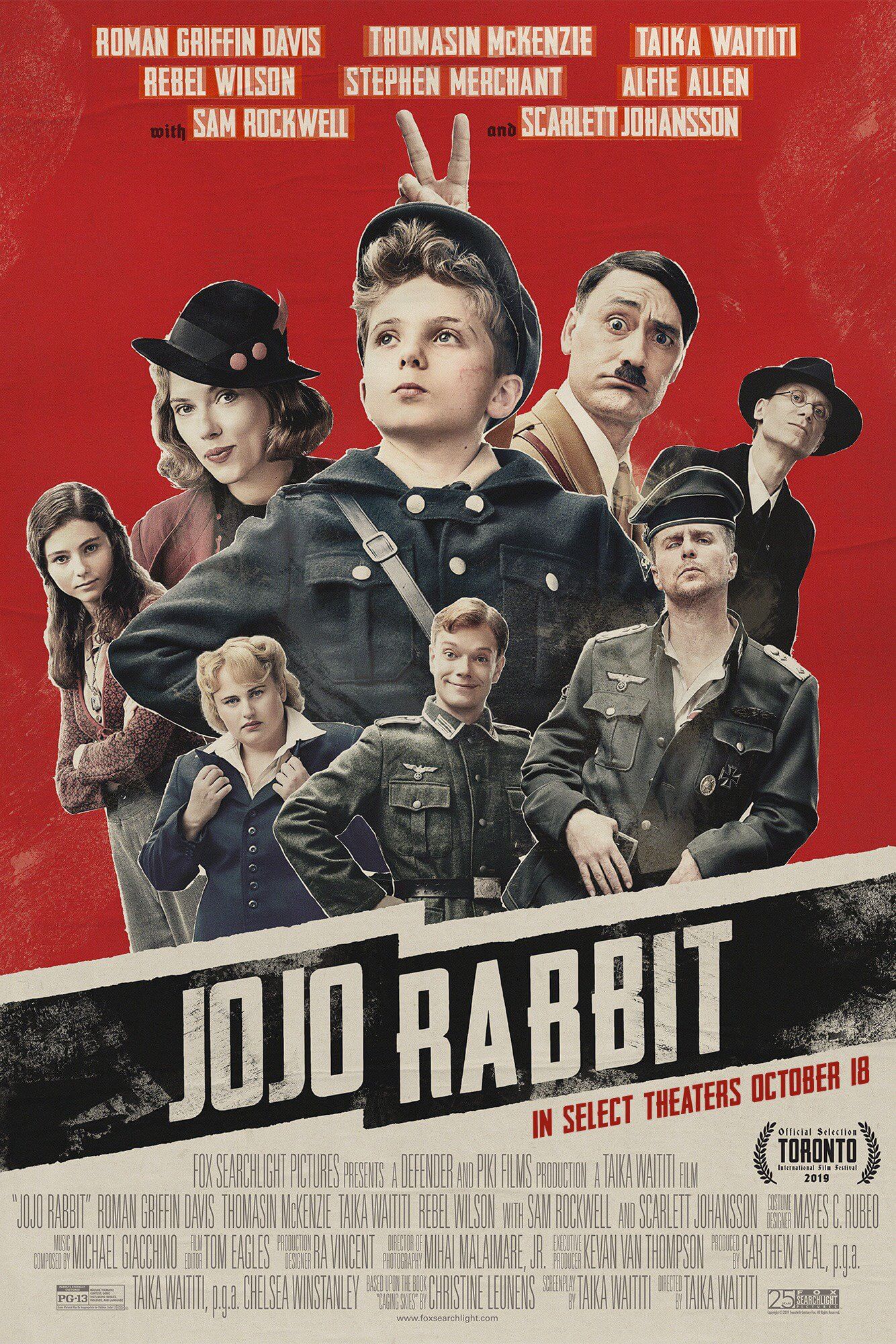

Taika Waititi plays Adolf Hitler in Jojo Rabbit, but a version of the Nazi leader who exists only in the mind of a young German boy. The 10-year-old Johannes Betzler, nicknamed “Jojo,” sees his Führer as an imaginary presence, fulfilling the “Hitler is every German boy’s best friend” sentiments of the regime’s propaganda. Jojo, an awkward outsider, has latched on to the idea of Nazism, unable to grasp its sinister meaning but clinging to its inclusive groupthink. It’s an unlikely setup for a feel-good comedy and condemnation of fascism, but the gamble works, resulting in a film that is playful, warm-hearted, sobering, and distinctly a product of its writer-director. Waititi based his screen story on Caging Skies, the 2008 novel by New Zealand-Belgian author Christine Leunens. Though the source material treats the subject matter with grievous veracity, the film retains only its narrative shell, resolving instead for a broad “anti-hate satire”—the ubiquitous statement, along with the bunny ears/peace sign of the film’s poster, employed by Fox Searchlight’s promotional team to ensure no neo-fascists somehow interpret the film as sympathetic to the Nazi cause. But there’s no risk of mixed messages here, as Jojo Rabbit feels like a whoopie cushion placed on the seat of hate groups.

Waititi has made some of the funniest, most heartfelt films of the last decade. After his 2007 debut on Eagle vs. Shark, Waititi’s first great film was Boy from 2010, a coming-of-age tale about a Maori family living near the Bay of Plenty in New Zealand. Like many of Waititi’s subsequent efforts, Boy told the story of youth in revolt, following an imaginative youngster who idolizes Michael Jackson and his own disappointment-of-a-father. And while Waititi has explored other, purely comic enterprises such as 2015’s What We Do in the Shadows, his films have mainly focused on matters of children struggling to grow up with deficient or unconventional father figures. In Hunt for the Wilderpeople (2016), a rebellious orphan is placed with a family, and Sam Neill’s curmudgeonly bushman has to take up the uncomfortable role of the father figure that the boy needs. Even Waititi’s Marvel extravaganza, Thor: Ragnarok (2017), told a story about the God of Thunder as a petulant child who must accept that he can never live up to his father’s legacy. Waititi’s protagonists often occupy the role of outcasts and misfits, whose idiosyncrasies and self-consciousness make them endearing. With these themes in mind, Jojo Rabbit feels right in line with Waititi’s body of work.

The film’s opening plays with the frenzied energy of Beatlemania, likening the rapturous screams of teenage girls over the Fab Four to the fervor behind the Nazi party. Waititi, who is of half Maori and half Russian-Jewish lineage, sets his opening credits against time-inappropriate clippings from concerts of The Beatles and the German-language version of “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” playing on the soundtrack, which features other German covers by Roy Orbison and David Bowie. The Second World War is drawing to a close, but Jojo (Roman Griffin Davis) is still “massively into swastikas”—his bedroom walls have been covered with posters of Hitler and Nazi propaganda. With his father away at war and his sister dead, Jojo relies on his mother Rosie (Scarlett Johansson, terrifically expressive), the source of the boy’s imaginative streak. She doesn’t approve of Jojo’s fandom or the war, but telling her son to toss the Nazi outfit could mean certain death for her. She must watch as Jojo regurgitates Nazi rhetoric about Jews being horned serpents with forked tongues, though it’s apparent he’s just a confused and lonely boy hoping to be accepted into the same group the other boys his age have joined. Given the layers of reality and fantasy at play, the film resembles a lighter take on the dark works of Guillermo del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), in which children process the barbarity of the real world through a supernatural metaphor.

The film’s opening plays with the frenzied energy of Beatlemania, likening the rapturous screams of teenage girls over the Fab Four to the fervor behind the Nazi party. Waititi, who is of half Maori and half Russian-Jewish lineage, sets his opening credits against time-inappropriate clippings from concerts of The Beatles and the German-language version of “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” playing on the soundtrack, which features other German covers by Roy Orbison and David Bowie. The Second World War is drawing to a close, but Jojo (Roman Griffin Davis) is still “massively into swastikas”—his bedroom walls have been covered with posters of Hitler and Nazi propaganda. With his father away at war and his sister dead, Jojo relies on his mother Rosie (Scarlett Johansson, terrifically expressive), the source of the boy’s imaginative streak. She doesn’t approve of Jojo’s fandom or the war, but telling her son to toss the Nazi outfit could mean certain death for her. She must watch as Jojo regurgitates Nazi rhetoric about Jews being horned serpents with forked tongues, though it’s apparent he’s just a confused and lonely boy hoping to be accepted into the same group the other boys his age have joined. Given the layers of reality and fantasy at play, the film resembles a lighter take on the dark works of Guillermo del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), in which children process the barbarity of the real world through a supernatural metaphor.

Early on, Jojo attends a Hitler Youth camp run by Captain Klenzendorf (Sam Rockwell), and the setting recalls Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom (2012), complete with tan uniforms and childish campsites. Klenzendorf, battle-worn and seemingly tired of the whole Nazi thing (yes, Rockwell plays yet another reforming racist), teaches the boys to “blow schtuff up,” while his assistant, the blonde and curvy Fräulein Rahm (Rebel Wilson), teaches the girls how to help the cause by getting pregnant. Jojo doesn’t have what it takes to be a Nazi, however. When he’s ordered to strangle a small bunny to demonstrate his willingness to kill, he refuses (and the audience sighs in relief), earning him the scaredy-cat name “Jojo Rabbit.” Regardless, he’s encouraged by Hitler, a Looney Tunes character in Jojo’s mind—who always has an encouraging word and makes an exit by leaping out the window (one suspects that if Hitler snuck up on someone, Waititi would have included the sound of plucking violin strings). After Hitler gives him a pep talk, Jojo resolves to steal a grenade from Klenzendorf to prove himself, but the outcome leaves the boy scarred and even more of an outcast. The material takes a turn when, forced to recover at home, Jojo learns that his mother has hidden a Jewish girl named Elsa (Thomasin McKenzie) in their walls. Fortunately, Jojo ignores Hitler’s suggestion: “Let’s burn down the house and blame Winston Churchill.”

Beyond the initial camp setting, Waititi shares more than a few aesthetic similarities to Wes Anderson, such as his use of vintage rock music or balanced camera movements. But these are surface-level comparisons. He’s also sillier and more buffoonish, while his films allow for more extreme highs and lows than Anderson’s deadpan quality. In the first moments of the film, Waititi places us into the realm of satire, where the tone shifts at jarring intervals, challenging the viewer to keep up as the film transitions from wacky comedy to Nazi dread to sentimental drama, sometimes in a single scene. It will be too much for some viewers unable to keep up and process the ever-changing emotional tenor, but those versed in Waititi’s intentional randomness and stylistic dexterity should feel up to the task. Jojo Rabbit’s change from a film about a boy’s absurdist imaginary friend to a high-stakes situation where Jojo, the young Nazi wannabe, finds an Anne Frank hiding in his home, may be too real or go too far for some. But as played by McKenzie, in another fine performance after last year’s Leave No Trace, Elsa becomes an essential humanizing force for Jojo.

When she first appears, Elsa confirms Jojo’s worst fears about Jews and confronts the tyke like a specter out of a J-horror movie. She warns him that if she’s turned in, Jojo’s mother will be killed for harboring her. Convinced to keep the enemy in his home a secret, Jojo resolves to write an informational book—filled with crude, boyish drawings—to perpetuate the Jewish myths with which the Nazis have brainwashed him. Elsa, indulging the boy to keep herself alive, helps his research by exaggerating the prejudiced fantasy at times. But the two lonely youngsters cannot help but form a sibling bond, even if a rivalry emerges too. At the same time, the Hitler of Jojo’s mind becomes jealous and hateful, a presence that Jojo no longer needs around. Waititi’s tonal balancing act here is nothing short of impressive, as he modulates scenes between goofiness and profundity in an instant. Watch the sequence when the Gestapo, headed by Stephen Merchant—in a role that sees his resemblance to Toht in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)—inspects Jojo’s home. Waititi fills the audience with laughter through the farcical “Heil Hitler” ritual, terror over Elsa’s potential discovery, and gladness over Jojo’s reaction. The film goes even darker toward the end, acknowledging the ruinous nature of the Nazi threat, and yet somehow Waititi never mismanages the blend of mockery and sincerity.

When she first appears, Elsa confirms Jojo’s worst fears about Jews and confronts the tyke like a specter out of a J-horror movie. She warns him that if she’s turned in, Jojo’s mother will be killed for harboring her. Convinced to keep the enemy in his home a secret, Jojo resolves to write an informational book—filled with crude, boyish drawings—to perpetuate the Jewish myths with which the Nazis have brainwashed him. Elsa, indulging the boy to keep herself alive, helps his research by exaggerating the prejudiced fantasy at times. But the two lonely youngsters cannot help but form a sibling bond, even if a rivalry emerges too. At the same time, the Hitler of Jojo’s mind becomes jealous and hateful, a presence that Jojo no longer needs around. Waititi’s tonal balancing act here is nothing short of impressive, as he modulates scenes between goofiness and profundity in an instant. Watch the sequence when the Gestapo, headed by Stephen Merchant—in a role that sees his resemblance to Toht in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)—inspects Jojo’s home. Waititi fills the audience with laughter through the farcical “Heil Hitler” ritual, terror over Elsa’s potential discovery, and gladness over Jojo’s reaction. The film goes even darker toward the end, acknowledging the ruinous nature of the Nazi threat, and yet somehow Waititi never mismanages the blend of mockery and sincerity.

Comedies about Nazis have always been controversial, and many commentators fail to see what’s so funny about them. When confronted by the Holocaust’s scope of atrocity, with some six million Jews murdered under the cover of war, it’s easy to understand why someone would deem Nazism unsuitable material for humor. Arguments against satirizing Nazis warn that humor deflates what should be lasting indignation over a hate group that achieved such power and carried out their genocidal agenda. Then again, the humorous approach attempts to remove that power by portraying Adolf Hitler to be an absurdist figure, while those who would follow or idolize him prove just as ludicrous in comedic hands. When Charlie Chaplin played on the fact that Hitler shared the Tramp’s iconic mustache in The Great Dictator (1940), he satirized the hatemonger with petty fixations and speeches in German-gibberish, turning Hitler into a transparent megalomaniac. In 1942, just a few months after Pearl Harbor, Ernst Lubitsch released To Be or Not to Be and make a joke out the self-seriousness and regimented protocols of Nazis. It would not be the last film to make a running gag out of the obligatory nature of the “Heil Hitler” salute. Later, Mel Brooks’ The Producers (1967) underscored the issue of Nazis as thorny subjects for humor when the musical “Springtime for Hitler,” designed to offend and flop, turns out to be a great success. Each of these films was criticized upon its release for employing humor to address the subject of Nazism, but they remain works that prompt discussion and laughter.

Jojo Rabbit’s detractors have remarked on the moral responsibilities of filmmakers who confront the subject of Nazism. When films treat such a grave and unthinkable subject with levity, some critics begin to sound like Plato, issuing censures that art should only exist if it serves a greater social purpose with apt seriousness. But film history has shown that Nazism and the Holocaust have provided the thematic backdrop to a myriad of films in a wide range of genres, often in a way that depicts them as indistinguishable from the purest evil (Nazis are the quintessential movie villains). Filmmakers address Nazism and the Holocaust in ways that make sense to them as artists, not always as commentators making a socially responsible and historically accurate statement at the most opportune cultural moment. One of the frequent comments against Jojo Rabbit is that it doesn’t paint Nazism as hateful enough, that it skimps on the horrific details of Nazi ideology in order to serve its comedic agenda. But these viewers are forgetting that the story is from the perspective of a German child, who would not know of such atrocities until confronted by them directly. Another frequent remark is that Waititi has made the wrong film for this moment, when neo-Nazism and intolerance have emerged in countries the world over. Suffice it to say, a comedy about Nazis is bound to draw attention and test the limits of the audience’s humor.

And yet, all the finger-wagging about social responsibility feels reductive and misses the point. After all, the viewership of Jojo Rabbit does not occur in a vacuum. Just as its humor has layers of irony and metatextuality, so does the experience of watching it. Viewers can negotiate the surface as a tenderhearted comedy that decries Nazism in general, while outside of the text, they remain fully aware of the Holocaust’s horror, regardless of whether or not Waititi offers a detailed reminder. His agenda seems less specific to the Nazis or the real Hitler than a general “Fuck off” to those who are propelled by hate. In that, it emboldens understanding, empathy, and curiosity about other human beings regardless of their race, religion, ethnicity, or sexual preference. It’s as much an immature middle finger at Hitler as it is a commitment to living life with a sense of joy and with love. When Jojo asks his mother what she’ll do after the war, Rosie replies that she’ll dance—it’s an act of pure freedom and expression that the Nazi regime drained from life. Of course, Waititi isn’t suggesting the world just dances its troubles away, but if people spent more of their time dancing and less time trying to achieve self-fulfillment through oppression, the world would be a better place. It’s idealistic, to be sure, but no less affecting.

And yet, all the finger-wagging about social responsibility feels reductive and misses the point. After all, the viewership of Jojo Rabbit does not occur in a vacuum. Just as its humor has layers of irony and metatextuality, so does the experience of watching it. Viewers can negotiate the surface as a tenderhearted comedy that decries Nazism in general, while outside of the text, they remain fully aware of the Holocaust’s horror, regardless of whether or not Waititi offers a detailed reminder. His agenda seems less specific to the Nazis or the real Hitler than a general “Fuck off” to those who are propelled by hate. In that, it emboldens understanding, empathy, and curiosity about other human beings regardless of their race, religion, ethnicity, or sexual preference. It’s as much an immature middle finger at Hitler as it is a commitment to living life with a sense of joy and with love. When Jojo asks his mother what she’ll do after the war, Rosie replies that she’ll dance—it’s an act of pure freedom and expression that the Nazi regime drained from life. Of course, Waititi isn’t suggesting the world just dances its troubles away, but if people spent more of their time dancing and less time trying to achieve self-fulfillment through oppression, the world would be a better place. It’s idealistic, to be sure, but no less affecting.

These are not complex ideas, but there’s an undeniable sophistication to their simplicity. Jojo Rabbit has an unlikely cuteness factor that will endear it to audiences (it won the People’s Choice award at the Toronto International Film Festival), and therein, spread its prevailing message that Nazis are assholes. It’s also an unabashedly sentimental film, with Johannson’s character offering hopeful advice (“As long as there’s someone alive somewhere, then they lose”) in the face of great evil, while she also personifies the extent to which the Nazis were capable of destroying something pure and good. In that sense, Waititi circumvents the mistakes of Roberto Begnini’s Life is Beautiful (1997), which turned the reality of the Second World War into a game. Of course, Waititi hasn’t made Jojo Rabbit into a comedy set in the world of Schindler’s List (1993); he leaves the worst of the Holocaust to documentaries such as Night and Fog (1955) and Shoah (1985). As argued above, the film isn’t about the Holocaust; Waititi’s message of anti-hate proves resounding and good-natured, leaving the audience firmly dismissive toward the film’s target: the hatred inherent to Nazi ideology. It’s a wonderful, energetic, and infectious experience that, for some, may feel like the wrong movie at the wrong time; for others, it’s just the opposite.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review