John Wick: Chapter 4

By Brian Eggert |

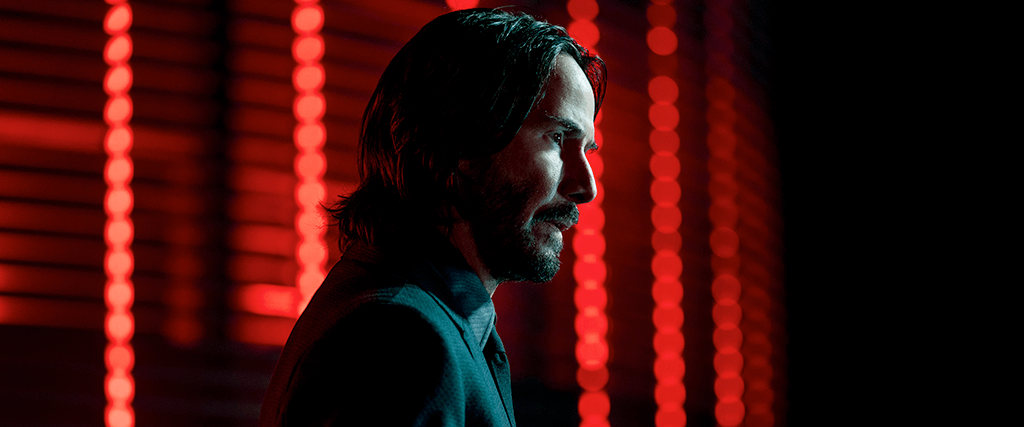

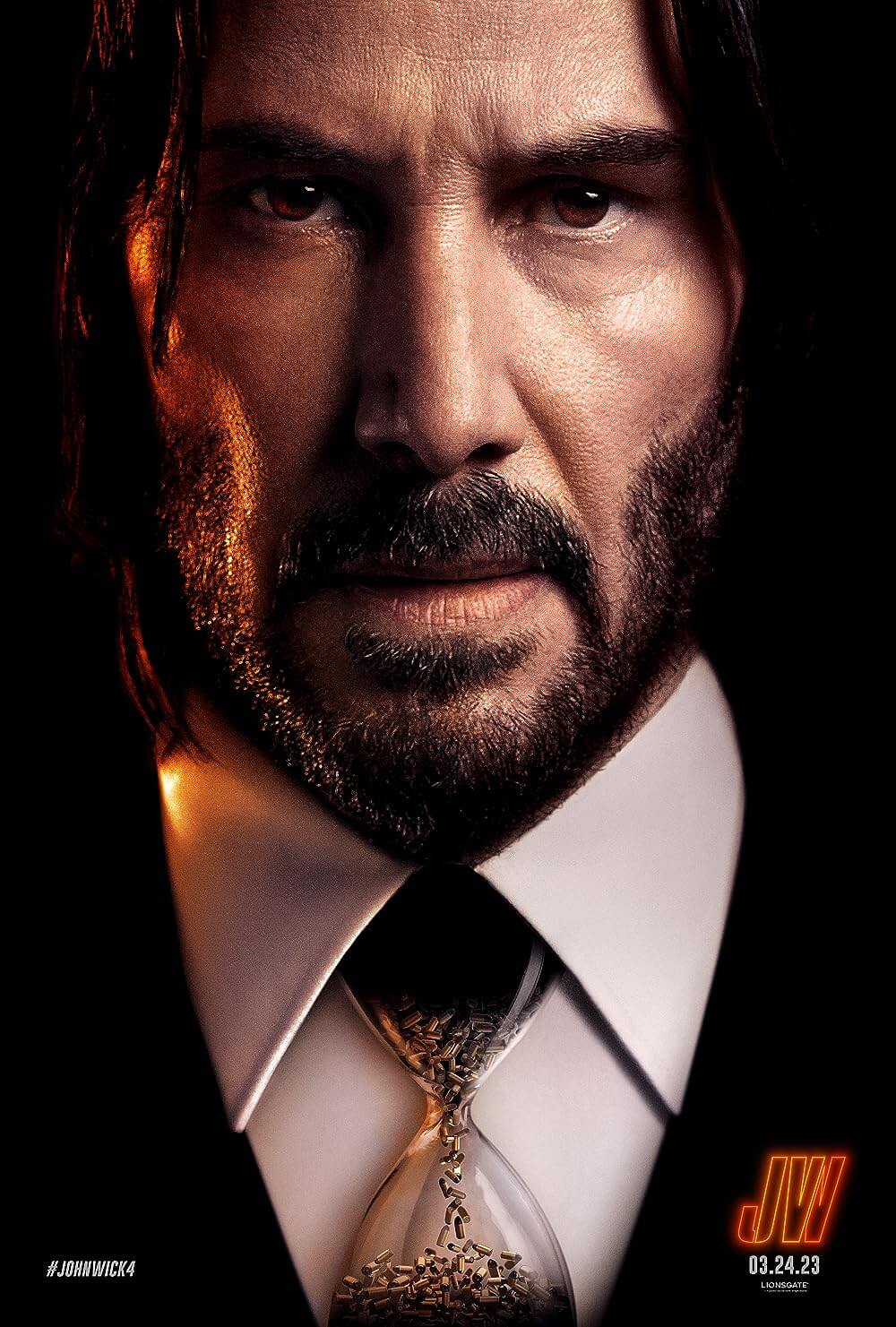

From the hellbound opening that quotes Dante Alighieri’s Inferno (“Abandon all hope, all ye who enter here”) to the finale outside Sacré-Cœur, John Wick: Chapter 4 deploys grand iconography in service of an epic shoot-em-up. The opening scenes set the stage with desert riders on horseback, silhouetted against a low sun—an allusion to Lawrence of Arabia (1962) that suggests the sprawling film to follow: a nearly three-hour procession of headshots and martial arts set against stunningly designed set pieces. The latest installment may not have the complex characterizations of David Lean’s magnum opus, but director Chad Stahelski commits to one striking display after another. Keanu Reeves returns to the titular role, which finds the well-dressed ex-hitman battling countless goons and boss-level baddies against momentous backdrops, including the Eiffel Tower and Arc de Triomphe in Paris; the neon-glowing streets of Osaka; and the New York City skyline. It’s a long and exhausting—but refreshingly never dull—spectacle of violence that’s easily the most ambitious and visually accomplished entry yet. Best of all, the filmmakers eventually lean into the over-the-top proceedings to explore the comic potential of increasingly bombastic martial arts entertainment.

Though Stahelski has directed each chapter thus far, the series has become ever more expansive, outlandish, and mythologized. In the 2014 original, the conflict between the former hitman and the band of Russian gangsters who killed his dog, the animal gifted to him by his late wife (Bridget Moynahan), seems like relatively low stakes now (however, in the sequels, there’s never been anything near the emotional blow of Wick losing his furry best friend). Chapter 2 (2017) and Chapter 3: Parabellum (2019) have gone off the rails to concoct an ever-unfolding world of hired guns and power hierarchies that test our suspension of disbelief. While those world-building flourishes remain engaging, each movie is more about one-upping the last one in terms of fight choreography, set design, and body count. Certainly, the latest is the most gorgeously photographed and conceived of the series. And unless the planned Chapter 5 introduces WMDs, it’s difficult to imagine any sequel with a higher death toll than Chapter 4, where hundreds of anonymous thugs meet their demise by Wick’s hand, sword, or gun.

Chapter 4 also represents a marked improvement over the last sequel by virtue of its villains. Whereas Parabellum featured Iron Chef America’s chairman (Mark Dacascos) in a hammy role, the new movie boasts martial artist Donnie Yen (controversial star of the Ip Man series) as a skilled assassin, B-movie action hero Scott Adkins as a seedy German gangster in a fat suit, and likable newcomer Shamier Anderson as a bounty hunter with a loyal dog—a considerable upgrade. The screenplay by Shay Hatten and Michael Finch propels the in-hiding John Wick on a mission to earn his freedom from the High Table, head of a global organization of assassins. Their top enforcer, Marquis Vincent de Gramont (Bill Skarsgård, using a goofy French accent), wants to kill the “idea” of John Wick, who maintains an almost mythic status as the order’s resident “Baba Yaga.” So the Marquis resolves to make an example of anyone who has befriended or given harbor to Wick. He also enlists Wick’s former friend, Caine (Yen), a sightless killer reluctantly compliant to the Marquis, to hunt Wick down. On the periphery, Anderson’s mysterious Nobody, an independent agent, tracks Wick, trying to hike the bounty before he strikes.

This time around, Wick says even less than usual, aside from the occasional monosyllabic “Yeah,” or the rarer line of matter-of-fact dialogue. When his old pal Winston (Ian McShane) asks where all this ends, Wick replies, “I’m going to kill them all.” Keanu is a deadpan presence here, his performance largely physical, alternating between precise pistol maneuvers and dancelike hand-to-hand combat. But gradually, a sly note of humor creeps into the fights. Even during the first major sequence, when Wick, taking refuge in Japan’s Continental Hotel—managed by an unwaveringly loyal friend (charismatic Japanese actor Hiroyuki Sanada) and his daughter (Rina Sawayama)—helps defend the place against the High Table’s forces, the action ventures into a showmanship that prompts bemused disbelief. At a certain point, the action has nothing to do with the story and everything to do with whatever Stahelski, a former stunt coordinator, conceives for the sequence. When Caine winds up his fist before socking an opponent, it’s not so much a real fight move as a comic flourish drawn from Popeye cartoons or perhaps Nintendo’s Punch-Out.

This time around, Wick says even less than usual, aside from the occasional monosyllabic “Yeah,” or the rarer line of matter-of-fact dialogue. When his old pal Winston (Ian McShane) asks where all this ends, Wick replies, “I’m going to kill them all.” Keanu is a deadpan presence here, his performance largely physical, alternating between precise pistol maneuvers and dancelike hand-to-hand combat. But gradually, a sly note of humor creeps into the fights. Even during the first major sequence, when Wick, taking refuge in Japan’s Continental Hotel—managed by an unwaveringly loyal friend (charismatic Japanese actor Hiroyuki Sanada) and his daughter (Rina Sawayama)—helps defend the place against the High Table’s forces, the action ventures into a showmanship that prompts bemused disbelief. At a certain point, the action has nothing to do with the story and everything to do with whatever Stahelski, a former stunt coordinator, conceives for the sequence. When Caine winds up his fist before socking an opponent, it’s not so much a real fight move as a comic flourish drawn from Popeye cartoons or perhaps Nintendo’s Punch-Out.

By the last third, Wick transforms into a modern-day Buster Keaton, with stony-faced reactions to the most absurd physical feats before him. Forget Keaton clearing the way for a train or having a building façade fall around him. Wick falls several stories out of a window onto a van, deflects countless bullets with his kevlar suit, survives being struck by multiple automobiles, and takes perhaps the longest fall downstairs in movie history. Of course, CGI and the work of stunt performers bring these moments to life, whereas Keaton was au naturel, but Keanu’s performance is no less rooted in the flat physical comedy of Keaton’s silent cinema. And realism be damned—the audience accepts that Wick is a superhuman impervious to harm, and his survival is less about thrills than I can’t believe I’m seeing this reactions. Yen, too, offers comic relief in punchy dialogue, as does McShane’s witty seen-it-all routine. The humor in the previous installments felt ungainly, but it aligns well with the progressively comical proceedings that accelerate in Chapter 4.

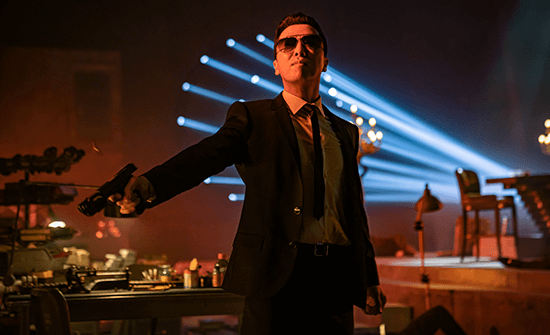

But the humor remains under the surface of Wick’s otherwise deadly serious mission, which is made grave by an early death that Wickiverse fans will mourn. Similarly, the samurai showdown between Yen and Sanada, illuminated by red lanterns and accented by a Japanese bell pavilion, draws from austere samurai cinema—Akira Kurosawa’s Sanjuro (1962) came to mind. Stahelski bounces effortlessly between severe and borderline absurdist tones, and he doesn’t receive enough credit for his tonal command. Once Wick arrives in Berlin and faces Killa (Adkins), the exaggerated quality of Stahelski’s work becomes impossible to deny. A creation of prosthetics, Killa has a grotesque face, gold teeth, and a body that recalls Colin Farrell’s transformation into the Penguin in The Batman (2022). Adkins plays the character, so he has the strength and maneuverability of a trained fighter—making for an incongruous and oddly funny amalgamation of the Kingpin and Fat Bastard. When Wick and Killa fight, it’s inside a German nightclub brimming with LED lights, curtains of water, and crowds of dancers so immersed in the loud techno music that they hardly notice everyone dying around them.

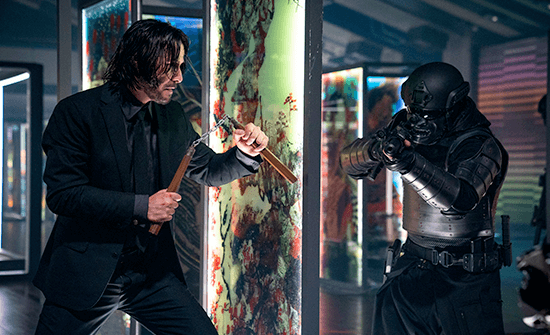

Working alongside Danish cinematographer Dan Laustsen, who has spent the last few years alternating between Guillermo del Toro projects and John Wick movies, Stahelski stages iconic set pieces like the Berlin sequence, each connected by thin plot tissue. In Osaka, Wick faces Caine in a museum of glass panels and samurai armor, the space shimmering with white panels, but not before a rooftop fight featuring red neon and a cherry blossom tree in full bloom. Later in Paris, there’s a series of fights that unfold across the city: a digitally extended overhead shot with incendiary rounds, recalling the bravado “spider” sequence from Minority Report (2002); an encounter on a roundabout amid cars that conspicuously don’t stop for a gunfight; and a fight up 200-plus stairs to the aforementioned basilica, perhaps inspired by the steep hill scene in the Jackie Chan actioner Supercop (1992). Each of them could stand alone, like an art installation of a beautifully filmed and arranged ballet of death, and each is set to the thumping electronic score by Tyler Bates and Joel J. Richard that kept my head bobbing and toe tapping. Through it all, Wick remains comically invincible thanks to his status as an action hero in a Hollywood movie.

Working alongside Danish cinematographer Dan Laustsen, who has spent the last few years alternating between Guillermo del Toro projects and John Wick movies, Stahelski stages iconic set pieces like the Berlin sequence, each connected by thin plot tissue. In Osaka, Wick faces Caine in a museum of glass panels and samurai armor, the space shimmering with white panels, but not before a rooftop fight featuring red neon and a cherry blossom tree in full bloom. Later in Paris, there’s a series of fights that unfold across the city: a digitally extended overhead shot with incendiary rounds, recalling the bravado “spider” sequence from Minority Report (2002); an encounter on a roundabout amid cars that conspicuously don’t stop for a gunfight; and a fight up 200-plus stairs to the aforementioned basilica, perhaps inspired by the steep hill scene in the Jackie Chan actioner Supercop (1992). Each of them could stand alone, like an art installation of a beautifully filmed and arranged ballet of death, and each is set to the thumping electronic score by Tyler Bates and Joel J. Richard that kept my head bobbing and toe tapping. Through it all, Wick remains comically invincible thanks to his status as an action hero in a Hollywood movie.

When Wick reaches the final sequence at a classical French standoff, complete with dueling pistols—a scene overly reliant on a CGI sunrise, unlike, say, Ridley Scott’s naturally staged duels in The Duellists (1977)—the film’s world tour of action movie archetypes is complete, leading to a fateful, intimate end. If the material doesn’t resonate with the emotional tenor it should, given some of Stahelski’s symbolic imagery and thematic underpinnings, the movie manages to enthrall from start to finish, delivering the standard “John Wick experience” in a bigger, bolder package than ever before. Chapter 4 asks the audience to embrace its unrelenting action and scopic vision, regardless of how many times Wick should have died. Sure, it’s another lengthy franchise sequel in Hollywood’s recent bid to justify the price of a movie ticket with evermore unyielding extravaganzas. But the film earns its runtime with its nonstop momentum, a memorable cast of characters, and no shortage of sights worthy of the big screen.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review