Reader's Choice

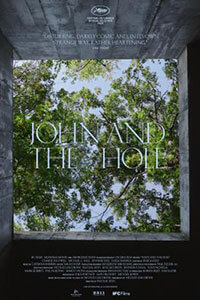

John and the Hole

By Brian Eggert |

“When do you become an adult?” asks the 13-year-old John (Charlie Shotwell) of his mother. Her response, apparently, doesn’t satisfy him. So John intends to find out for himself. He drugs his yuppie parents, Anna and Brad (Jennifer Ehle, Michael C. Hall), along with his kindly sister Laurie (Taissa Farmiga), and somehow carts them in a wheelbarrow and lowers them into a nearby concrete hole—part of an unfinished bunker in the woods by their house. He leaves them down there for days, making wordless visits to deliver food and clothing, ignoring their pleas for help. Director Pascual Sisto’s debut feature, John and the Hole, delves into a coming-of-age nightmare in decidedly symbolic terms. John, a remote and inexpressive boy whose issues with empathy suggest a personality disorder, stumbles upon the hole in the woods. It seems like a perfect place to put his family since they already exist at a remove. So he drops them into the abyss, reversing their roles by placing them into his position of feeling powerless. John’s behavior cannot help but recall the Zellner brothers’ disturbing Kid Thing (2012), about a juvenile delinquent tomboy who finds a woman trapped in a hole and resolves to keep her there.

Shotwell portrays a fascinating monster. Having appeared in 2021’s The Nest and Captain Fantastic (2016), he’s an accomplished young actor, capable of subduing his expressions to create a stone-faced cipher with John. Sisto’s calibration of every performer is impressive, though he leaves the trapped family with few gradations. They behave like the families in Yorgos Lanthimos’ Dogtooth (2009) or The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017). They’re affected and somewhat stilted, implying that their dynamic might have a more significant representative meaning, if not an intentionally inscrutable quality that suggests the film’s didacticism. The film’s mise-en-scène hints at this as well. Filmed in a boxy aspect ratio (a technique adopted by many arthouse filmmakers these days), John and the Hole creates a sense of claustrophobia, mirroring the perspective of John’s family from down in the hole. The narrowed frame also represents John’s borderline tunnel vision, as though he’s trying to understand the world before him. At one point, John tells his tennis coach, “I want to be who I am.” But John is still trying to figure out what that means.

John behaves like the distant cousin of the little girl from Michael Haneke’s Happy End (2017), who poisons her hamster, then her mother, and then wheels her suicidal grandpa into the sea. He also recalls shades of the manipulative teen in Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011), with a dash of Tom Ripley when he eerily mimics his family’s voicemail messages. In other words, John might be a psychopath. Then again, he might be the product of a coddled upbringing in a privileged, upper-middle-class bubble. His parents shield him from reality, such as describing the bunker, clearly meant as a bomb shelter, as a place to “hide from a big storm.” They don’t want John exposed to concepts like a nuclear apocalypse; however, there might be a negative consequence to protecting him from all forms of negativity. Bored adolescent boys have a knack for finding trouble, no matter how well their parents protect them. With his family trapped in the hole, John invites over his friend Peter (Ben O’Brien), and they eat junk food, zone out to video games, spit in the house, and test the limits of drowning each other. Boys will be boys.

Birdman (2014) screenwriter Nicolás Giacobone, adapting his own short story, also includes three curious scenes: The first appears at the 30-minute mark, about the time the titles first appear onscreen. A 12-year-old girl named Lily (Samantha LeBretton) sits in her room alone, and her mother Gloria (Georgia Lyman) soon joins her. They talk about how the girl’s father has disappeared, and he may not come back, and so Gloria resolves to tell Lily a story called “John and the Hole.” Then the film returns to John and his family, apparently a fiction wrapped in a loose framing device. After another half-hour, we return to Lily and Gloria, having almost forgotten about them. Now the mother is leaving. Now the mother tells Lily she must fend for herself, and there’s enough cash in the house to survive alone for a year. Now Lily will be alone, even though she desperately wants her mother to stay. The film’s last image, too, rests on a cryptic shot of Lily walking through the woods by the bunker, which seems to take place sometime after the events with John. What do we make of these scenes? Few other critics have mentioned them, but Sisto appears to place them at strategic moments in the narrative.

Consider that John and the Hole is a parable about how some children grow up too fast and others never grow up at all. John wants to grow up faster than he’s capable. As a counterpoint, Lily isn’t ready to be thrust into such responsibility. I kept thinking that Lily’s absent father might be Brad and that her father’s sudden disappearance might be because John put Brad in the hole. Does Brad have a second family as part of an elaborate experiment to raise two children in different extremes? Likely not, given the reference to “John and the Hole” in Lily’s scenes. Still, the film functions like a prompt and leaves room for interpretation, albeit not with the same degree of satisfaction as a Lanthimos or Haneke film. It doesn’t work as a thriller about a messed-up kid, and it feels incomplete as a metaphoric exploration of youth, especially given the open-ended conclusion. But Sisto has nonetheless created a fascinating film that one cannot watch passively. What you make of it might depend entirely on your experiences and how you project them onto John.

(Note: This review was originally suggested, commissioned, and posted on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review