Joe

By Brian Eggert |

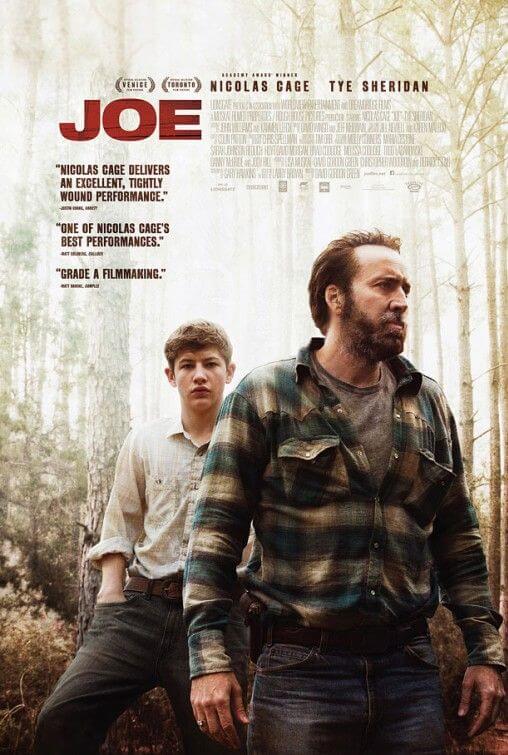

With Joe, director David Gordon Green returns to his roots with another rough-hewn indie drama set in the American South. Before making several Hollywood gross-out comedies like Pineapple Express and Your Highness, Green earned a reputation as an important voice in American cinema with titles like George Washington, Undertow, and Snow Angels. Green’s film of Larry Brown’s 1991 novel of the same name saturates its audience in a dirt-poor small town populated almost exclusively by aggressive drunkards, hard-luck cases, and miserable people living in less than optimal conditions. But the film’s unforgiving, often grating portrayal of Southern waste is redeemed by thoughtful performances from Nicolas Cage and his younger costar Tye Sheridan.

Screenwriter Gary Hawkins moved the story from Brown’s Mississippi location to Texas, where Green’s last film, the redeeming indie comedy Prince Avalanche took place. Joe begins on the train tracks with Sheridan’s teenage Gary scorning his worthless, downright evil father Wade (Gary Poulter, who died just after the production wrapped), a crusty, abusive bastard and alcoholic with no intent to support his family. Sheridan has played this role before—twice, in fact—first for Terrence Malick in The Tree of Life as Brad Pitt’s middle son, next in Jeff Nichols’ Mud. How fitting, since the long-established Malick has greatly influenced both Nichols and Green with his early masterworks Badlands (1973) and Days of Heaven (1978). Although seemingly destined to play boys searching a strong father figure, Sheridan is nonetheless excellent in the role.

Gary finds such a figure in the titular character, Cage’s tattooed and bearded Joe Ransom. Approaching fifty and struggling to suppress his hair-trigger temper, Joe keeps himself busy running an illegal operation where he poisons trees so a lumber company can plant more profitable saplings. Despite a checkered past that includes prison time, Joe is a decent man, evidenced in his chummy relationship with the hard-luck folk around town, including the ladies at the local whorehouse, a blind man, and his own crew of day laborers. When Gary wanders onto Joe’s job site looking for work, he gets a position poisoning trees, which becomes a symbol of Gary’s toxic relationship with Wade that only worsens throughout the film. Beyond Wade’s generally terrible and later murderous behavior, Joe must stand up for Gary by contending with Willie (Ronnie Gene Blevins), a scar-faced sicko who bears unrelenting grudges against both Joe and the boy.

Cage may have soured his own reputation with the general public after countless dreadful action movies, but he’s an actor capable of incredible range—evidenced in Adaptation. and Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, even in the underrated Knowing. Cage is capable of portraying inner demons in subtle ways; he embodies Joe with incredible weight, the character smoking and drinking to bury something inside him, not unlike his Oscar-winning turn in Leaving Las Vegas. But if Joe drinks too much, that something is unleashed with a vengeance, usually on the poor sap police officer who tries to pull him over. Fortunately, Joe also maintains a friendship with the sheriff. But without Cage’s grimacing presence drenched in booze and garbed in plaid flannel, and his occasional moments of humor (including the actor’s funny self-parody where Joe teaches Gary to smile through pain to “look cool”), Joe‘s unyielding, arguably exaggerated sense of Southern authenticity would begin to wear on the viewer more so than in Green’s earlier films.

Following a very familiar narrative trajectory that has much in common with the aforementioned Mud, as well as Green’s earlier works, Joe reaches its climax after a slow-burning build toward violence. It’s a poignant finish to a film whose sense of realism is steeped in an overwhelming sense of ugliness. With reprieve found in the natural performances by Cage and Sheridan, the film tests the viewer’s patience for raw drama about unfortunate and beaten-down characters. Still, Green’s treatment, along with the gorgeous lensing by his regular cinematographer Tim Orr, captures the beauty in the wasteland setting, populated by weathered characters, rickety condemned houses, and fields filled with abandoned boats. All of these battered elements are offset by the soulful father-son relationship at the center, as well as a poignant last scene that invites a sense of hope to otherwise bleak surroundings.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review