Reader's Choice

Jodorowsky’s Dune

By Brian Eggert |

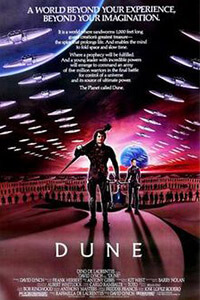

About the only thing Alejandro Jodorowsky gets right about Frank Herbert’s Dune is when he compares the novel to Proust. “It’s science fiction, but it’s very, very literary,” says the surrealist filmmaker. Jodorowsky’s Dune is a documentary about the avant-garde director and his failed attempt to adapt Herbert’s text back in the mid-1970s, a production called the “greatest film never made.” Frank Pavich directs the doc and makes a stirring case that the adaptation would have made a monumental, groundbreaking motion picture, except Jodorowsky proved too unpredictable for any major studio to trust with the considerable budget necessary to make it. Though he assembled some impressive talent for a meticulously storyboarded project outline, Jodorowsky’s production stalled, and the producers ultimately abandoned the idea. The proposed film belongs on a list of unrealized projects by equally ambitious and impractical auteurs that spark “What if?” conversations among cinephiles—stuff like Stanley Kubrick’s Napoleon project, David Cronenberg’s sequel to The Fly, and various productions by Orson Welles.

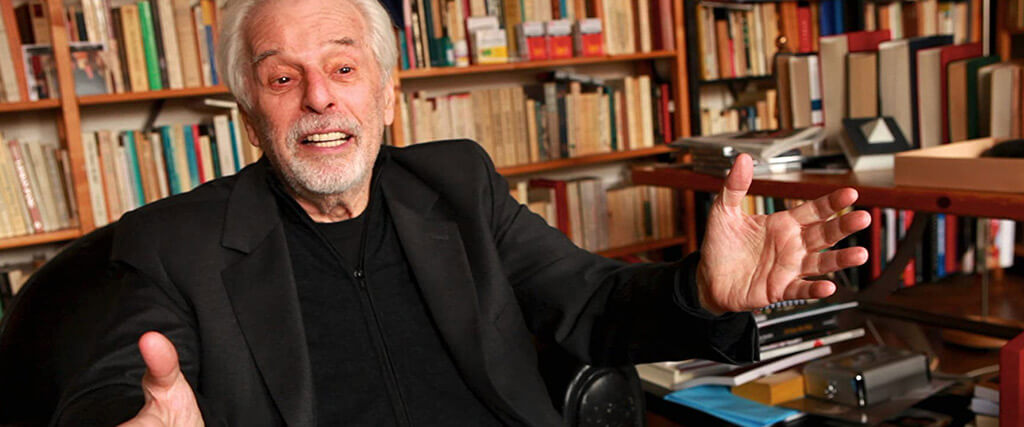

While the documentary drools over what might have been, it also aggrandizes Jodorowsky, suggesting that no artist was purer or more revolutionary at the time—and thus, Dune’s failure could not be his fault. Born in Chile, Jodorowsky spent much of his early career between Paris and Mexico, where he worked on comic strips and directed experimental theater productions. In 1968, he decided to try filmmaking, and his debut Fando y Lis was eventually banned in Mexico for its taboo subject matter and unconventional structure. His next two works, El Topo (1970) and The Holy Mountain (1973), became objects of cult fascination. The former was, arguably, the first true “midnight movie” and received an enthusiastic following; the latter, though less successful, shocked with its bizarre, psychedelic imagery. Next, French producer Michel Seydoux encouraged Jodorowsky to pursue whatever inspired him, and the director settled on Herbert’s source material, which he had not read. And so, Jodorowsky rented a castle (as one does) and wrote his screenplay based on the 1965 book. Hoping to create the cinematic equivalent of an LSD trip, he wanted to portray “something sacred” like “the coming of a god” through Dune’s hero, Paul Atreides.

It’s somewhat exhilarating to watch a filmmaker in his eighties give an animated interview about a project that, at the very least, would have been a compelling visual experience given the people involved. Jodorowsky set out to find “spiritual warriors” to work on the picture, artists who would approach the material with a level of passion. Jodorowsky hired French comic-book artist Moebius to craft the storyboards, which show incredible cinematic movement and framing. Chris Foss, a cover artist of science-fiction books, designed spaceships and architecture (that look like the Maryland state flag). Swiss artist H.R. Giger created some grim biomechanical images for the Harkonnen planet. For his score, Jodorowsky convinced Pink Floyd and the French concept band Magma to provide original music. His cast would include the likes of Udo Kier, David Carradine, and Mick Jagger. His 12-year-old son would play Paul, but Jodorowsky demanded that the boy become Paul by undergoing a rigorous martial arts regiment—training for six hours a day, seven days a week, for two years. Rounding out the cast, he agreed to pay Salvador Dalí’s asking price of $100,000-a-minute to play the Emperor of the Known Universe, and Orson Welles would play the bulbous Baron Harkonnen.

If you think this all sounds inspired if somewhat far-fetched, you wouldn’t be wrong. Jodorowsky’s vision for the project included distinct artists and talents who, each one on their own, could distinguish a picture. All of them together feels almost gluttonous, like too many individual styles. Still, the director’s ambitious ideas, like an opening shot that “traverses the whole universe,” remain eye-popping, as Pavich uses animations to make Moebius’ storyboards come to life. But then you start to see the ornate, multicolored costumes and hear wacky ideas—like Dalí’s demand for a giraffe on fire—and the project begins to seem like a mess. Herbert purists might feel taken aback by Jodorowsky’s approach to adaptation. Troublingly, he compares an unfaithful adaptation to a sexless marriage, and how, if one hopes for children, one must resort to “raping the bride… with love.” If possible, set aside the disturbing imagery and what it might imply about Jodorowski’s view on marital relations and procreation. In effect, the director admits to using the source material as a launching pad for his own creative experiment. Doubtless, Herbert fans would have been disappointed by the director’s artistic license; Jodorowsky enthusiasts would be delighted.

If you think this all sounds inspired if somewhat far-fetched, you wouldn’t be wrong. Jodorowsky’s vision for the project included distinct artists and talents who, each one on their own, could distinguish a picture. All of them together feels almost gluttonous, like too many individual styles. Still, the director’s ambitious ideas, like an opening shot that “traverses the whole universe,” remain eye-popping, as Pavich uses animations to make Moebius’ storyboards come to life. But then you start to see the ornate, multicolored costumes and hear wacky ideas—like Dalí’s demand for a giraffe on fire—and the project begins to seem like a mess. Herbert purists might feel taken aback by Jodorowsky’s approach to adaptation. Troublingly, he compares an unfaithful adaptation to a sexless marriage, and how, if one hopes for children, one must resort to “raping the bride… with love.” If possible, set aside the disturbing imagery and what it might imply about Jodorowski’s view on marital relations and procreation. In effect, the director admits to using the source material as a launching pad for his own creative experiment. Doubtless, Herbert fans would have been disappointed by the director’s artistic license; Jodorowsky enthusiasts would be delighted.

In any case, the director’s out-there ideas ultimately raised red flags in Hollywood. Seydoux sent a massive tome, which detailed every aspect of Dune’s proposed production, to every major Hollywood studio, hoping to find an investor to cover the remaining budget. But when studios learned that Jodorowsky wanted a film that ranged anywhere from 12 to 20 hours, they told Seydoux, “We don’t get your director.” Jodorowsky’s Dune places the blame for the project’s collapse on money-minded studios who didn’t have the vision to see the genius of what the misunderstood Jodorowsky had conceived. Director Nicolas Winding Refn (Drive), hyperbolic as ever, claims that Hollywood feared what Jodorowsky’s film would do to society. After all, the director hoped Dune would “give a mutation to young minds,” causing a kind of collective social change. Pavich frames Jodorowski as a messianic artist preaching to a crowd of Hollywood naysayers. And yet, the documentary tends to ignore that unfortunate reality of filmmaking: it’s an industry that’s almost inextricable from commerce, especially where multimillion-dollar budgets are concerned.

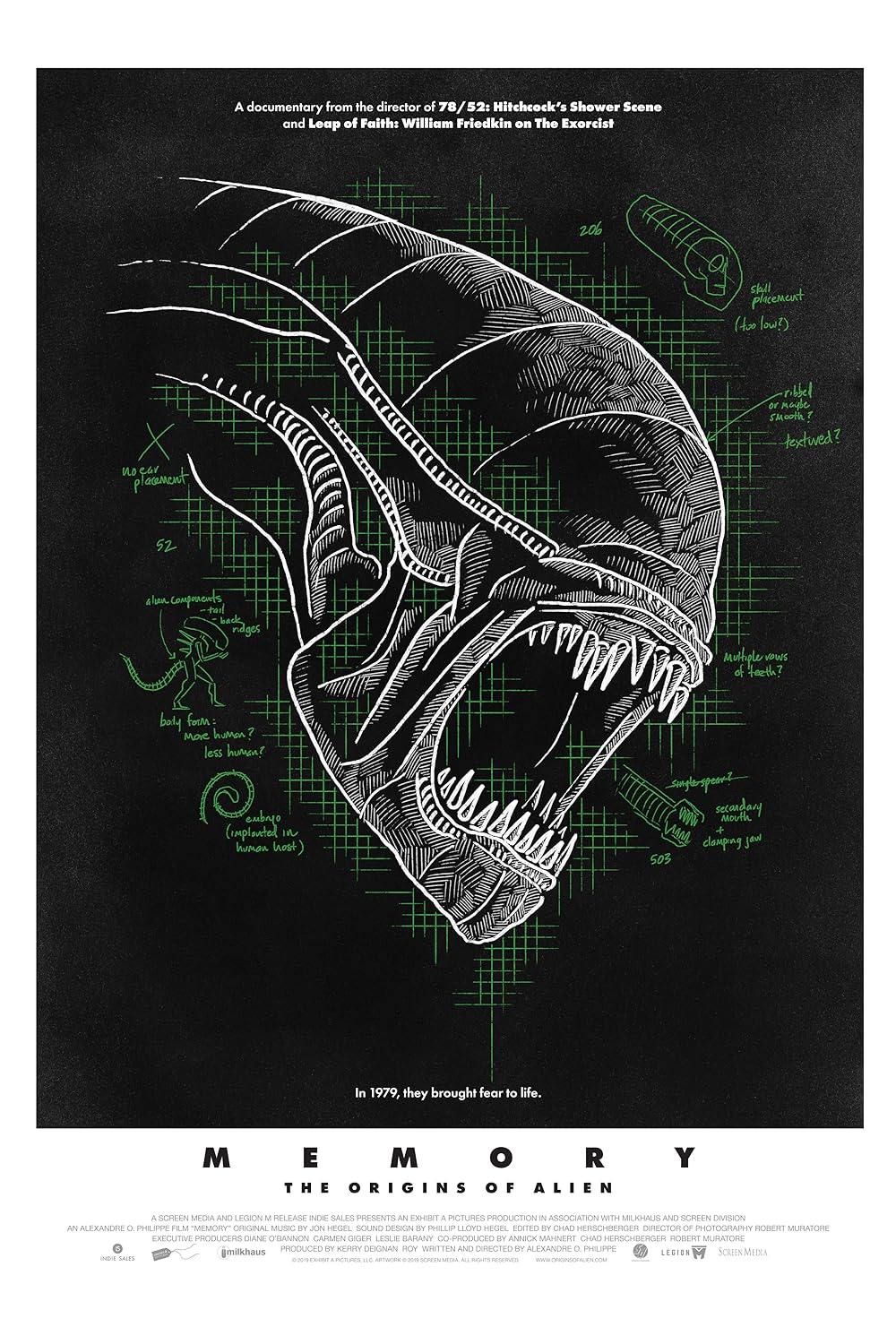

One of Jodorowsky’s “spiritual warriors” was Dan O’Bannon, the co-writer and special FX designer on John Carpenter’s first feature, Dark Star (1974). After Dune fell through, O’Bannon returned to Hollywood and began work on Alien (1979), and used artists like Moebius and Giger to bring a level of distinction and creativity to that picture, thus elevating science-fiction as Jodorowsky had hoped to. Herein lies the most fascinating aspect of Jodorowsky’s Dune. Seydoux sent the Dune book to Hollywood and, though every studio passed on the project, they clearly used the book as a reference in future productions. Filmmakers borrowed imagery here and there to inspire the production design of Star Wars, Flash Gordon, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Contact, among many others. Jodorowsky also repurposed a few of his ideas in his subsequent comic book collaborations with Moebius.

As for the documentary, it’s decidedly more commonplace, offering a few other interviewees besides those involved in the failed production of Dune. Where Devin Faraci is the resident film historian and cult film nerd, the perspective is narrow. Jodorowsky remains center stage, his English is subtitled (unnecessarily) due to his thick accent. At one point in the film, the director’s Siamese cat interrupts the interview, and Pavich waits for Jodorowsky to bring the feline into his lap and unceremoniously resume his train of thought. Moments like this feel overly fascinated with every movement, every word coming out of the director’s mouth. Even so, it’s easy to empathize with someone as driven as Jodorowsky, who felt somewhat crippled after his Dune project collapsed, even if it’s doubtful that it would have become as the director suggests, “The most important picture in the history of humanity.”

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review