Jersey Boys

By Brian Eggert |

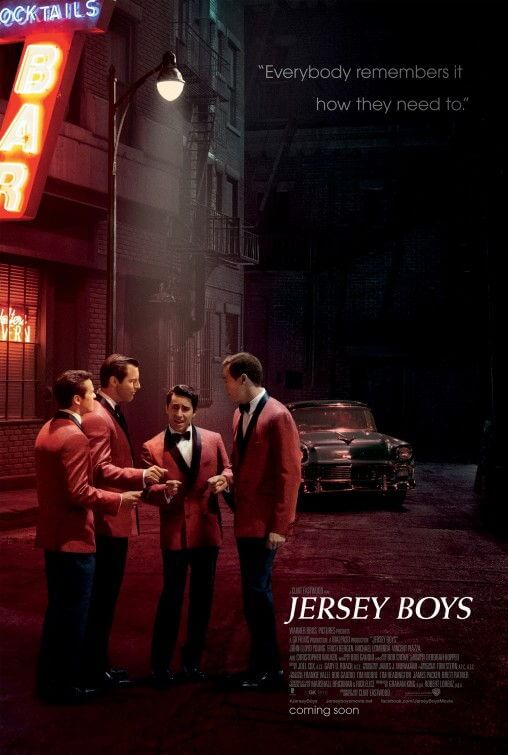

“When everything dropped away and all there was was the music… That was the best.” So says Frankie Valli in a sentiment not shared by his story’s teller, Clint Eastwood. The 84-year-old filmmaker takes on directing duties for the film adaptation of Jersey Boys, the long-running hit Broadway musical that won four Tony Awards after its debut in 2005. By following the story of the mob-backed Valli and the Four Seasons, Eastwood’s film spends more time on the messy backstage drama than celebrating love for the tunes themselves. At times, it seems like a Goodfellas-inspired tale about the mob’s heyday, but elsewhere it feels like a typical musician biopic, and it’s all wrapped up in a perspective-shifting structure reminiscent of Rashomon. Alternating between these incongruous styles, the film never resolves what it wants to be—although it’s evidently not about the music. The stage version’s original writers Marshall Brickman and Rick Elice developed the story for film by adding more theatrics and additional dialogue, but they lessen the joy of the storytelling by reducing the Broadway show’s virtually wall-to-wall jukebox sounds of the 1960s.

Indeed, Jersey Boys can scarcely be called a musical, though the group’s on-stage performances feature heavily in the latter half of the film. One dares suggest that Eastwood, however versatile a filmmaker through various genres, was mismatched with this material, which is a surprising notion given his music-oriented background. Though he directed the Charlie Parker biopic Bird (1988, starring Forest Whitaker) and the documentary Piano Blues (2003), scored seven of his films, and sang country in Honkytonk Man (1982), Eastwood’s firmly established love of music doesn’t necessarily mean he’s attuned to the snappy, energetic presentation this production required to both channel the Broadway show and ensnare moviegoers. Eastwood has long been a measured, gently paced filmmaker whose stylistic panache is that of visual restraint and emotional intensity. His approach on Jersey Boys is predictably his own and lacks the popish pizazz that would usually accompany such a tale. The result feels more like a leisurely, would-be Martin Scorsese picture than what it should—something more in the realm of Tom Hanks’ That Thing You Do! (1996).

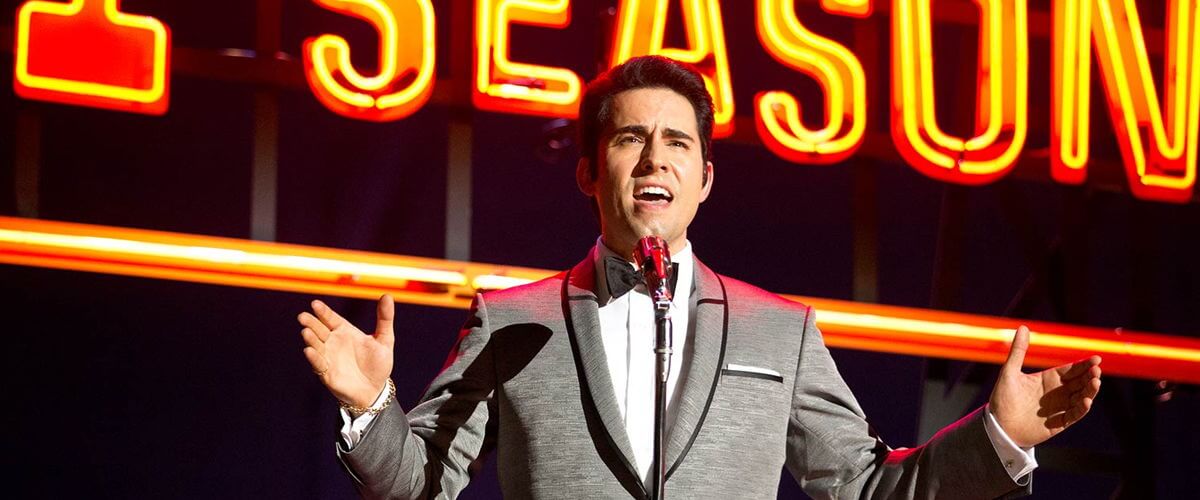

Eastwood’s film begins in Belleville, New Jersey, in the early 1950s, with a scene that has parallels in both Scorsese’s Goodfellas and The Departed. In a barbershop, singing teenager Frankie Castelluccio (John Lloyd Young) has earned enough trust from underworld mob boss Angelo “Gyp” DeCarlo (Christopher Walken) so that he’s allowed to give the man a shave, and that trust plays an integral role later on. Known for his buttery falsetto voice, Frankie becomes entangled with criminal Tommy DeVito (Vincent Piazza), botching an ill-conceived robbery and narrowly avoiding jail. But the hotheaded and self-centered Tommy knows the newly renamed Frankie Valli is a gold mine and, along with part-time felon and bassist Nick Massi (Michael Lomenda), enlists Valli to sing in his group, named The Romans and later The Four Lovers. As they struggle to get a break, hopeless talent scout Joe Pesci (Joseph Russo, playing the Goodfellas actor) introduces the trio to Bob Gaudio (Erich Bergen), the educated songwriter of the hit “Short Shorts”, whose presence makes all the difference amid the three mooks. Before long, they align with producer Bob Crewe (Mike Doyle, playing a rather stereotyped gay man) and rename themselves The Four Seasons.

Like most musical biopics, big moments in the film swell around the formation of hit singles and never into deeper tracks; here, “Sherry”, “Big Girls Don’t Cry”, and “Walk Like a Man” are prominently featured, but not until about midway through the 2-hour-and-14-minute runtime. And once the group releases a few No. 1 chart-toppers, the usual troubles follow: domestic turbulence, personal tragedies, infighting among the band, and an extended strain concerning Tommy’s money mismanagement. Through it all, each of the four members narrates a segment of the story, breaking the fourth wall, although their perspectives aren’t so ingrained into their section that the audience recognizes the truth has been grossly distorted by the speaker. Piazzi’s part has an entertaining cartoonish quality, but the other performances aren’t so interesting: Young, reprising his Tony Award-winning stage role, never has a chance to define Valli’s motivations; Bergen’s straight-laced Gaudio seems smug, yet he’s plainly the only clear-headed member of the band; and Lomenda’s Massi is a tall, doofy-looking, quiet type who sounds off too late. They’re distinct characters, but none are performed as three-dimensional. Additionally, Young, Bergen, and Massi had each played their roles in the musical’s various staged productions, but Piazzi (better known as Lucky Luciano on Boardwalk Empire) is a new addition, and his singing voice is less featured.

Each of the actors sang live during filming, as opposed to the standard of lip-synching prerecorded tracks, but Eastwood’s choice has become popular as of late (see Les Misérables from 2012). This is an oddly realistic choice for Eastwood’s production—otherwise so rooted in palpable Hollywood artifice. Corny rear-projection scenes while driving look (intentionally?) generic and more attuned with the film’s 1960s setting, while Tom Stern’s usually sharp cinematography suffers from a few clumsy movements in interior conditions. Stern’s color palette is saturated and immersed in a period-appropriate look; however, sometimes, its appearance is murky and seems poorly lit. Studio backlots were unmistakably used, but then again, it remains unclear whether or not Eastwood intended his production to look the part and just implemented it patchily, or if the production itself is just sloppy. Given Eastwood’s track record, you should suspect the former but, deliberate or not, the effect is inconsistent and confuses the viewer almost as much as the story’s shifts in genre.

Either there are too many clichés in Jersey Boys or there aren’t enough. Eastwood avoids an embrace of staged musical numbers and dancing (until the incongruous end credits sequence where the cast dances through the streets of Belleville, at least) and pushes for a semi-realistic portrayal, except the story is so familiar within its genre that Eastwood should have out-performed its formulaic structure by delivering one helluva show—an energetic opposite to the dull end result. That, or he should have avoided the musical biopic blueprint altogether and tried something new. But the film resides somewhere in the discomfited middle-ground between theater-to-film flamboyance and stark period realism. And like everything Eastwood touches as of late, Jersey Boys is quietly watchable, if all-too-familiar and, not unlike J. Edgar or Invictus, a little boring. Still, given the film’s many correlations to Martin Scorsese, one cannot help but imagine what a more visually energetic filmmaker like Scorsese would have done with the material to enliven the music and integrate it more crucially into the story.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review