Reader's Choice

Jerichow

By Brian Eggert |

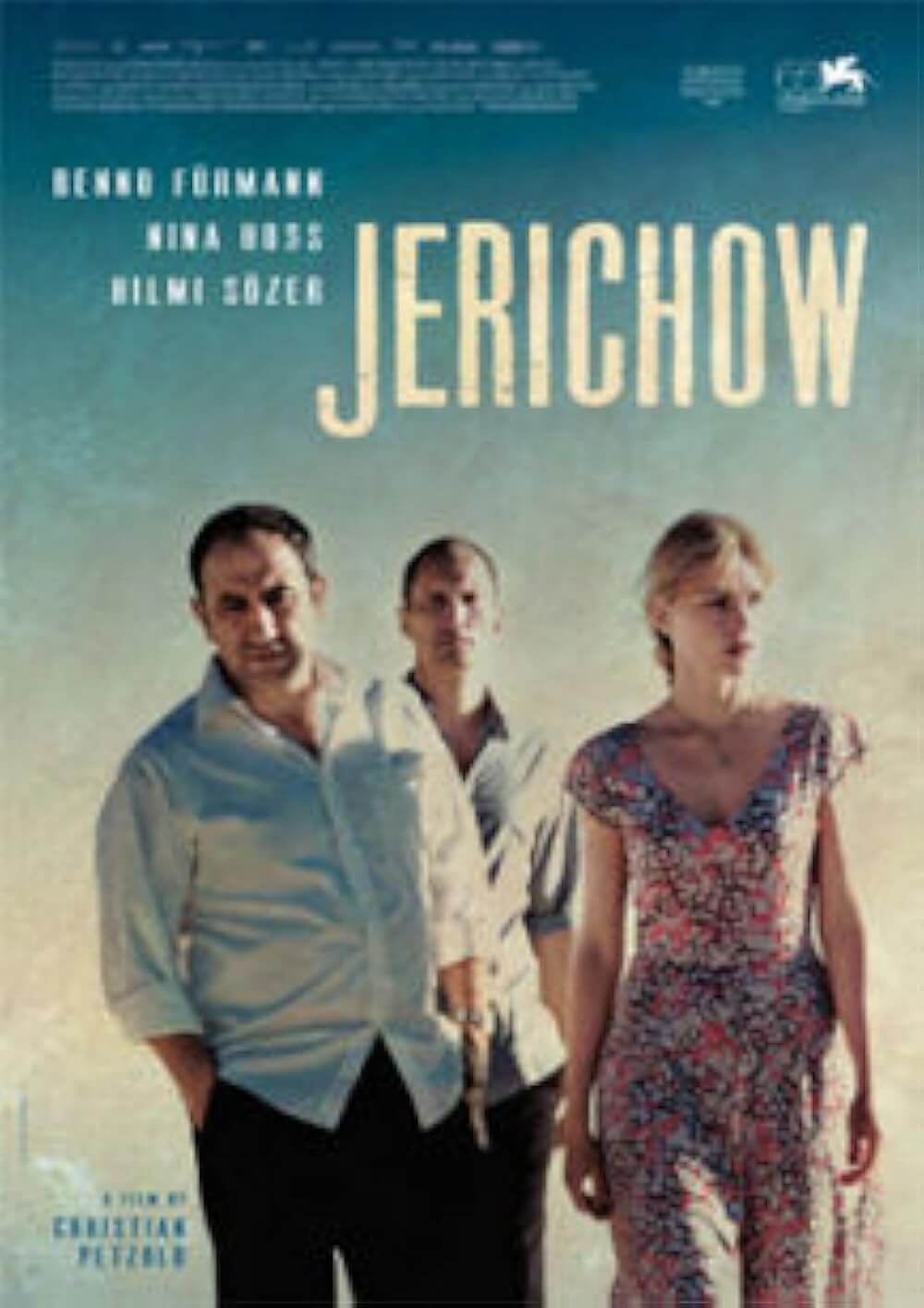

Jerichow, the umpteenth adaptation of James M. Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice, demonstrates that good source material has no limit to the number of times it can be adapted to the screen. As long as filmmakers find new and inventive ways to reshape the text, the story will keep resonating with audiences. Although most American viewers probably know the 1934 book from one of Hollywood’s adaptations—a 1946 version with Lana Turner and John Garfield, and a 1981 version with Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange—plenty of other directors the world over have tailored the scenario to their needs. French (Le Dernier Tournant, 1939), Italian (Ossessione, 1946), and Hungarian (Passion, 1998) productions have used Cain’s tale of lust and greed as a framework, changing details here and there to reflect their respective cultures. German director Christian Petzold does something similar with Jerichow, reformatting a familiar story into a commentary on class, ethnic, and gender differences in the continuous ripples of German reunification. At its center, however, remains a damn engrossing story about a dangerous love triangle.

Petzold frequently explores intimate, interpersonal stories that represent some larger historical or sociopolitical undercurrent in German culture. Although last year’s Transit seemed downright allegorical, films like Phoenix (2015), set just after World War II, and Barbara (2012), set in the East Germany of 1980, used their respective historical periods to confront the scars of German identity. And so it’s somewhat unexpected to look back at Jerichow and discover that it takes place in the here and now, or at least 2008, the year of its release. Nevertheless, Petzold uses Cain’s story to underline disparities that have persisted since the East-West division. The three central characters, for instance, each represent outsiders in the dominant German culture since the reunification. Thomas (Benno Fürmann), a former soldier who served in Afghanistan before receiving a dishonorable discharge, hails from the titular region, once part of East Germany, and comes from a lower economic class. Ali Özkan (Hilmi Sözer), a Turkish immigrant and successful businessman who has lived in Germany almost his entire life, remains alienated from his country because of his ethnicity. Laura (Nina Hoss), Ali’s wife, is the deep-in-debt woman caught between two men in a patriarchal society.

Petzold adheres to the requirements of pulp fiction by tightening the bonds between his three characters, making each desperately need the other. Thomas, unemployed and penniless, happens upon Ali, who drives his vehicle into a ditch while intoxicated. Ali eventually loses his license for drunk driving, and he needs Thomas to help with his snack cart business. Paid to drive and make deliveries for Ali, Thomas cannot help but notice his employer’s wife, who does the books. The tensions between husband and wife are palpable, making way for a passionate connection between Thomas and Laura. Of course, the stranger and the wife have their primal sexual drives in common—the kind of passion that finds them embracing on the floor, using their hands to muffle their moans—but also something more. Thomas’ vague past of criminal misdeeds aligns with Laura’s backstory, which entails prison time and massive debt from which Ali rescued her. Even if they weren’t already destined for each other, Ali pushes Thomas and Laura together by insisting that his new employee gaze upon and even dance with his wife, whom he presents like a trophy, yet also, curiously, guards with fervent jealousy. In an insidious kind of way, Petzold directs the viewer to want Thomas and Laura, the two more attractive people on the screen next to the portly Ali, to be together.

But if there’s any lesson to be learned from crime fiction writers like Cain, it’s that you should never try to cross a paranoiac. However, unlike previous iterations of Cain’s story, the rich husband isn’t a cruel beast, not entirely. He’s a tragic figure who drowns his estrangement in booze and dreams of returning to Turkey where he might feel at home. His business, which seems almost foreign in a region of the former GDR now acclimating to capitalism, has brought him some wealth, but he still has to fight to preserve his dignity. Vendors try to strongarm and swindle Ali, and Thomas becomes a bodyguard and enforcer when necessary. Which is to say, Ali isn’t the husband-as-dope character found in Cain’s similarly plotted Double Indemnity. He’s an empathetic figure who happens to be the most complex character on screen, cast out by his wealth and ethnicity, and deeply sad. “I’m stuck in a country that doesn’t want me, and with a wife that I bought,” he laments, all but announcing his sense of isolation. Still, he’s far from an innocent victim when Laura and Thomas plan to murder him and pass it off as a suicide—a scene of violence reveals Ali’s possessiveness over Laura and her desire to escape, but it doesn’t quite justify his murder in the viewer’s eyes.

But if there’s any lesson to be learned from crime fiction writers like Cain, it’s that you should never try to cross a paranoiac. However, unlike previous iterations of Cain’s story, the rich husband isn’t a cruel beast, not entirely. He’s a tragic figure who drowns his estrangement in booze and dreams of returning to Turkey where he might feel at home. His business, which seems almost foreign in a region of the former GDR now acclimating to capitalism, has brought him some wealth, but he still has to fight to preserve his dignity. Vendors try to strongarm and swindle Ali, and Thomas becomes a bodyguard and enforcer when necessary. Which is to say, Ali isn’t the husband-as-dope character found in Cain’s similarly plotted Double Indemnity. He’s an empathetic figure who happens to be the most complex character on screen, cast out by his wealth and ethnicity, and deeply sad. “I’m stuck in a country that doesn’t want me, and with a wife that I bought,” he laments, all but announcing his sense of isolation. Still, he’s far from an innocent victim when Laura and Thomas plan to murder him and pass it off as a suicide—a scene of violence reveals Ali’s possessiveness over Laura and her desire to escape, but it doesn’t quite justify his murder in the viewer’s eyes.

What works so well about Petzold’s take on Cain’s material, beyond his figurative representation of certain societal dynamics in Germany, is how each character demands our consideration. Petzold has a habit of writing characters with reserved emotions, requiring small outbursts to give some indication of what his characters are holding back. Jerichow unfolds with a great deal of quiet. Cinematographer Hans Fromm captures scenes in unobtrusive camera movements and few close-ups, while the score by Stefan Will seems recessive. Nothing about Petzold’s treatment feels arch or juicy in the manner one might expect. We can see the situation from everyone’s perspective, but none of them deserves to die, nor has the world dealt them cards from a rigged deck. To be sure, Petzold resists turning his film into a genre exercise. Laura hasn’t transformed into a vicious femme fatale, though Hoss’ performance is steely and suspicious. Thomas hasn’t become a soulless killer, but the humanity behind Fürmann’s eyes is only matched by his capacity for deception. And by the climax, Petzold manages to realign our sympathies and complicate the triangle in unexpected ways, allowing the final wordless moments to linger with the viewer well into the credits.

Petzold outlines a bitter critique of desire and capitalist ambition in Jerichow, and he implicates the viewer. Thomas and Laura lust for each other, and we want to see their forbidden desires materialize, just as we want to see these poor and unfortunate characters steal from the rich husband and escape. At the same time, Ali’s ambition to acquire a successful business and wife—the things expected of him by Western society—has not brought him the happiness he was promised. And it’s their plotting that kills Ali, whose sorrowful existence has left him broken, betrayed, and ultimately doomed. Ali’s response to this remains confronting and undeniable, and a decisive provocation on Petzold’s part given the material’s history. Jerichow once more reveals Petzold as a filmmaker who makes subtle turns of plot and layered characterizations, accompanied by predictably nuanced performances, out of otherwise conventional tropes. From start to finish, we never think about how Petzold reconsiders genre and text; instead, we remained engrossed by his particular investigation of these characters in their setting.

(Note: This review was suggested by supporters on Patreon.)

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review