Janet Planet

By Brian Eggert |

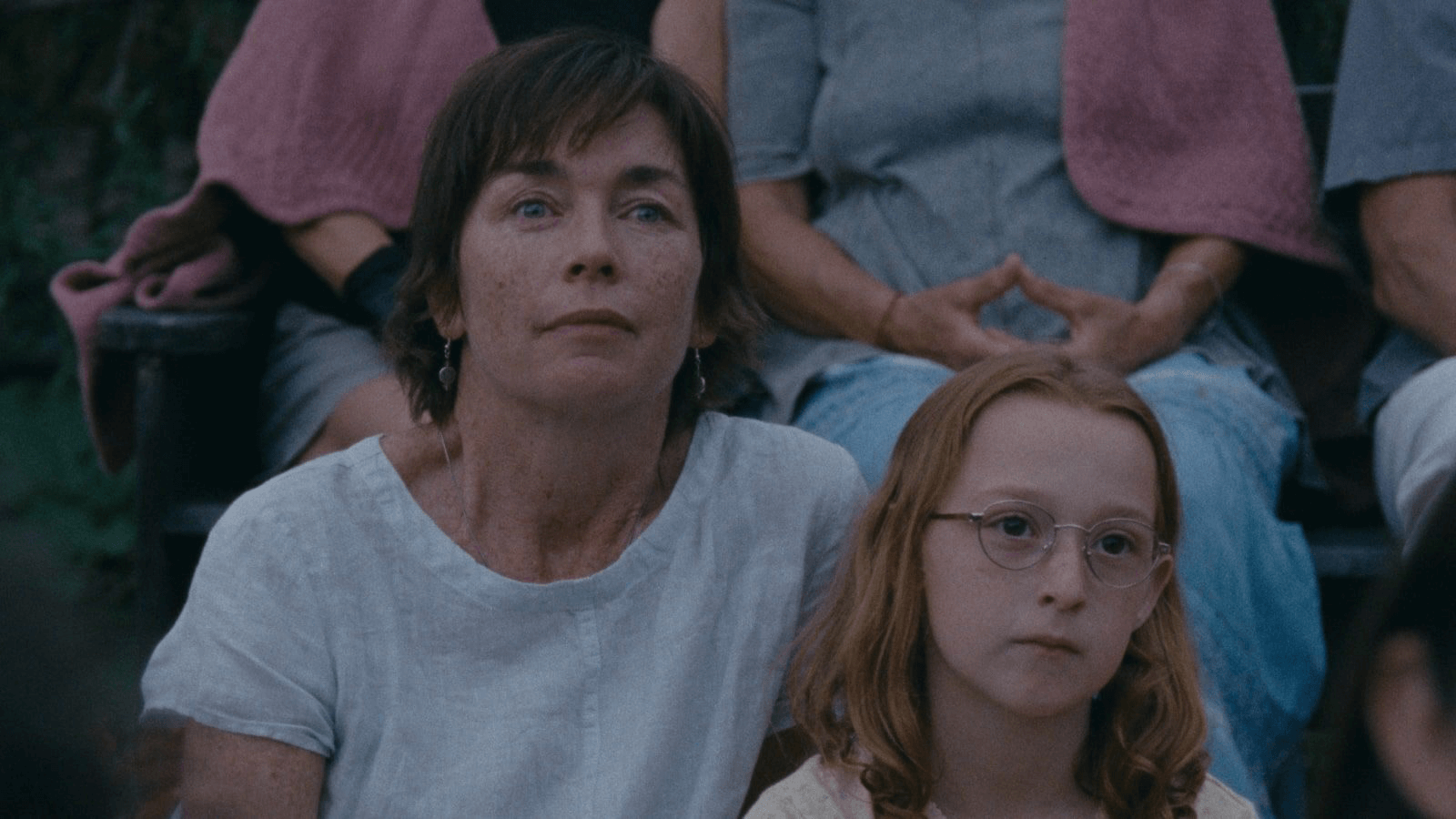

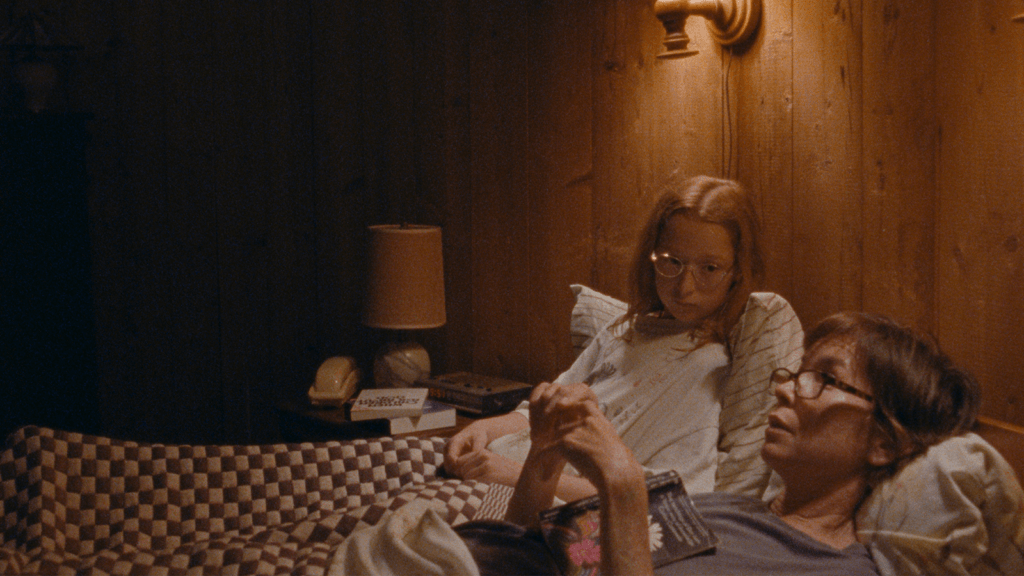

“Hi. I’m going to kill myself.” That’s what the 11-year-old Lacy says to her mother after sneaking out in the night at summer camp to use the phone. Then she clarifies, “I said I’m going to kill myself if you don’t come and get me.” This sharp declaration cuts through the otherwise serene setting, devoid of diegetic music and filled with crickets chirping and frogs croaking in the night’s emptiness. In Janet Planet, the filmmaking debut of playwright Annie Baker, Lacy and her titular mother have a close relationship. The daughter clings to her mother in a manner some might see as stifling. In one scene, Lacy asks, “Can I have a piece of you?” And she takes a single hair from her mother’s head to comfort her when she sleeps in her own bed. So, the separation that summer camp brings is simply impossible. Because of Lacy’s possessive love, the film is structured around the people who come into Janet’s life and often go because of Lacy. Played by a committed Zoe Ziegler and a measured Julianne Nicholson, Lacy and Janet have a distinct relationship, not strictly unhealthy but unconventional in a bohemian kind of way. Whereas a child threatening suicide might raise alarms in another household, Janet concedes to the demand and, with understanding, picks her up with a nonjudgmental smile and reassuring hug. The film has a similar comforting quality, without relying on nostalgia or sentimentalism, only acceptance.

Set in pastoral Massachusetts, Janet Planet unfolds in 1991, amid passive time and seemingly inconsequential dramaturgy. This is the stuff of Baker’s stage work, such as her Pulitzer Prize-winning drama from 2014, The Flick, about three arthouse cinema employees who talk after the feature while sweeping up popcorn and mopping sticky auditorium floors. Baker is known for embracing stage silence and resisting grand emotional gestures in her work. Her approach goes beyond minimalism and finds profound life lessons from what, on the surface, look like banal situations. These lessons must be extracted from what isn’t articulated by her dialogue or characters, and from the assumptions we make about what Baker doesn’t reveal. The filmmaker is careful about how she relays information, investing much of her film’s time in Lacy’s inner world, dwelling on her aimlessness and boredom during the empty summer days, with nothing else to do except attend piano lessons, laze around the house, and insert herself into her mother’s relationships. On paper, the film might even resemble a preadolescent coming-of-age story set during summer break. However, much of Baker’s approach also inhabits Janet’s space, creating a portrait of their functional codependency.

Chapters announce the end of each relationship Janet has in the film. When Wayne (Will Patton)—her moody live-in boyfriend, who has a daughter about Lacy’s age from a previous marriage—lashes out during a migraine, Janet asks Lacy what she should do, perhaps already knowing the answer. “I think you have to break up with him,” the girl admits. Then the title appears: “End Wayne.” Such is the film’s pattern, with new people coming and going, each new entry and closure announced with titles. But even when a given scene doesn’t seem to be about Lacy, it is. Note the conversation between Janet and her friend Regina (Sophie Okonedo), who moves in with them. The old friends take psychedelics and have a near-profound discussion in a long sequence where the camera remains on the two of them, only for Lacy to reveal, hilariously, that she’s been in the scene all along. After Regina breaks up with a charismatic New Age guru named Avi (Elias Koteas), who has some real cult leader energy, Lacy watches as he redirects his attention to her mother. Since Lacy is accustomed to either being alone or in the company of her mother, anyone, even a prospective friend her age, seems like an outsider and someone to be wary of. Even so, she yearns for a friend; the figurines on her shelf in her bedroom, hidden behind a curtain, aren’t enough.

Baker’s film is about Lacy’s private world, but it’s also about the spell that breaks between a daughter and her mother. While various other adults look to Janet for companionship, Lacy’s demands for her mother’s attention are never enough. Her precocious pleas for attention (“You know what’s funny? Every moment of my life is hell,” she remarks matter-of-factly) become her default mode, and Janet sometimes struggles to address them adequately in Lacy’s eyes. Isolated in a round country house where her mother performs acupuncture—the film’s title takes the name of her business—Lacy has almost nowhere else to direct her attention. Like every other character in the film, she orbits around Janet, suggesting the cutesy double meaning of the title. Though, Lacy’s inner life is rich and imaginative, from experimenting with Regina’s alternative shampoos in secret to telling lies about why she has to leave camp. Lacy’s utterly convincing inquisitiveness makes watching her fascinating, and Ziegler’s unselfconscious performance never feels like the work of an actor but the behaviors of an authentic personality. Similarly, Nicholson’s effortless role is masterfully restrained, an embodiment of her character’s radiant appeal that draws so many into her gravity, but Janet is also marked with sadness. She respects her daughter’s autonomy too much to discipline her, even if it means she subjects herself to inconvenient and awkward situations.

Baker’s film is about Lacy’s private world, but it’s also about the spell that breaks between a daughter and her mother. While various other adults look to Janet for companionship, Lacy’s demands for her mother’s attention are never enough. Her precocious pleas for attention (“You know what’s funny? Every moment of my life is hell,” she remarks matter-of-factly) become her default mode, and Janet sometimes struggles to address them adequately in Lacy’s eyes. Isolated in a round country house where her mother performs acupuncture—the film’s title takes the name of her business—Lacy has almost nowhere else to direct her attention. Like every other character in the film, she orbits around Janet, suggesting the cutesy double meaning of the title. Though, Lacy’s inner life is rich and imaginative, from experimenting with Regina’s alternative shampoos in secret to telling lies about why she has to leave camp. Lacy’s utterly convincing inquisitiveness makes watching her fascinating, and Ziegler’s unselfconscious performance never feels like the work of an actor but the behaviors of an authentic personality. Similarly, Nicholson’s effortless role is masterfully restrained, an embodiment of her character’s radiant appeal that draws so many into her gravity, but Janet is also marked with sadness. She respects her daughter’s autonomy too much to discipline her, even if it means she subjects herself to inconvenient and awkward situations.

Baker’s Janet Planet aesthetic is fully conceived and executed. Maria von Hausswolff, whose cinematography captured unearthly natural spaces in the 2022 Icelandic period piece Godland, shoots the picture with distinct, soft images in largely natural light. Her framing alternates between an adult’s perspective and a child’s-eye-view, often cutting all but the top of Lacy’s head out of the scene. Using 16mm cameras, von Hausswolff’s images are evocative, appearing washed-out by the summer and faded like a distant memory or an old photograph. Lucian Johnston’s editing deploys a longer-than-average shot length, allowing the viewer to live in the film’s extended conversations—ranging from Janet’s impression that Lacy may want to date another girl one day to the origin of the universe. Aurally, sound designer Paul Hsu records authentic audio from a Western Massachusetts forest for the production, and those subtle details fill the picture when it seems like nothing is happening in the story, leaving no moment empty. The sheer volume of ambient noise and heightened sound effects, such as room noise or shoes on gravel, has a transportive property.

Although Baker avoids nostalgia (aside from the Clarissa Explains It All theme song in one scene), she nonetheless teleports the viewer into their memories. The space in Janet Planet allows the mind to draw connections between what’s onscreen and our lives—not in a disengaged, wandering way, but rather in a way conjured by personal experiences. Lacy’s loneliness, idleness, and relative solitude reminded me of the summers I experienced in rural Minnesota around her age, around the same time, when I spent countless hours in my head, developing peculiarities and attempting to figure things out. Lacy wants to leave the safety of her carefully crafted and controlled reality with her mother and make new friends, yet she’s anxious, and her mother is a protective womb. It’s a similar worldview conveyed by Carol Reed in The Fallen Idol (1948), with a child who worships an adult but ultimately must reconsider their obsession. At the same time, Janet yearns to escape and find alone time. It’s worth questioning whether her final picnic with Avi actually happens, or if she lied about it for some solitude.

Steeped in minimalism and naturalism, Janet Planet runs for nearly two hours and can often seem like a vibe in its leisurely structure. Its various titles supply containers, each eventful for Lacy but not traditionally dramatic. Baker isn’t interested in her characters hashing out their differences or opening their baggage on the screen. But she’s fascinated by the long silences and empty space that Lacy fills with her imagination and love for her mother. Baker also delicately establishes the tension that emerges in Lacy when anyone else comes into Janet’s life, and in Janet when she feels helplessly stifled by her daughter. Still, watching Janet Planet, the experience can be oppressively quiet, alienating impatient viewers. Baker’s rather hypnotic filmmaking might register as slow and empty to some, but then, this A24 release isn’t interested in catering to mainstream sensibilities. My first time watching it, I could barely focus on the low-decibel film because of the festival audience’s general restlessness. I saw it again under better conditions, and the experience improved, even overwhelmed. Seen with receptive moviegoers open to giving themselves over to this film, there’s much beauty and nuanced character work to behold. Seldom are debut features this accomplished.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review