Jackie

By Brian Eggert |

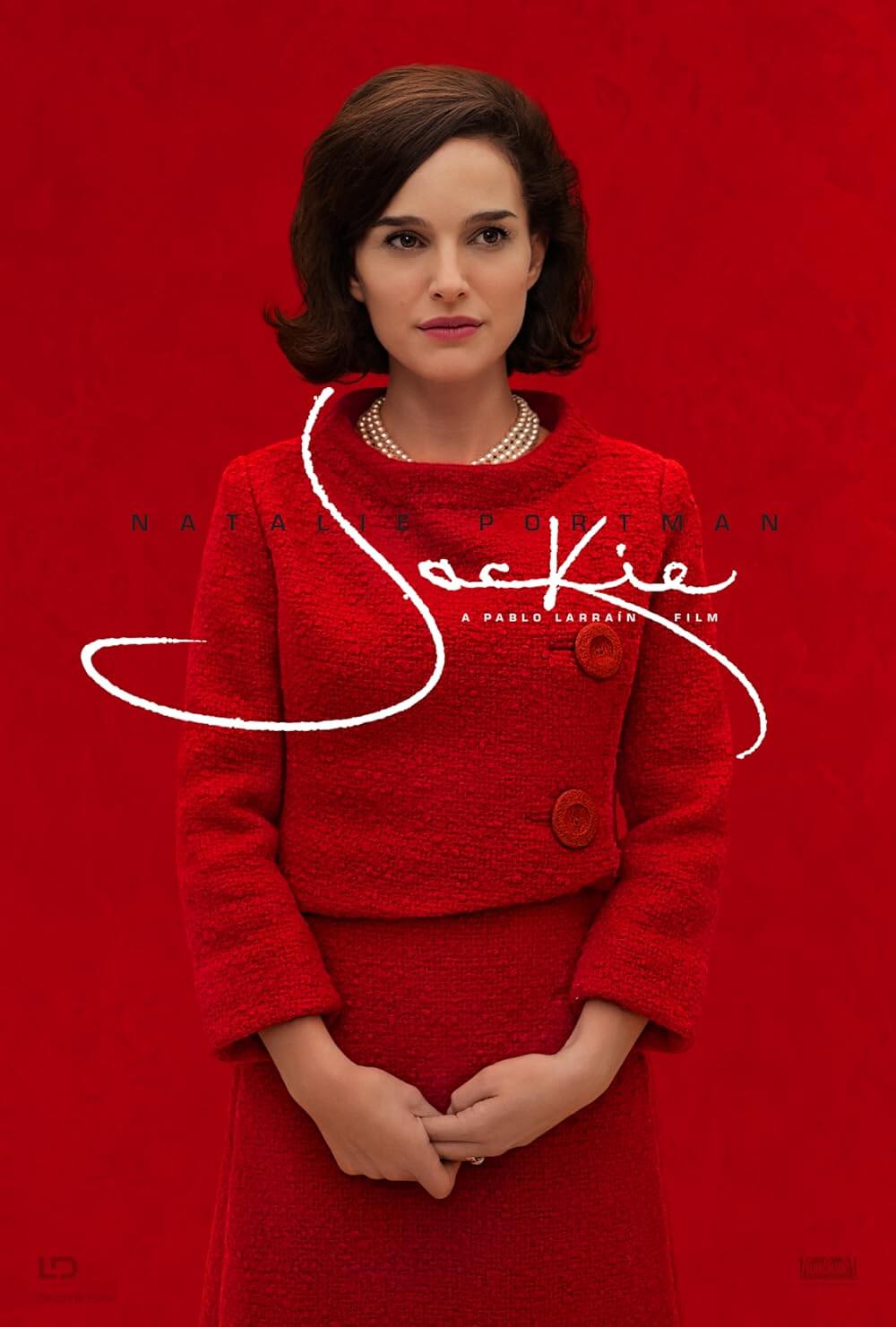

Natalie Portman plays Jacqueline Lee Bouvier Kennedy Onassis in Jackie, an uncommon biopic that looks at its subject through a narrow frame, rather than a sweeping (and ultimately insufficient) birth-life-death story. Chilean director Pablo Larraín arranges a film that opens with dissonant, falling chords by composer Mica Levi, whose score for Under the Skin remains some of the most memorable music of the last decade. Levi’s grandiose and tragic notes underscore the drama of this picture, as Jackie considers its subject just after the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963. The music and thematic dramaturgy of the film announces a fallen empire from Jackie’s perspective, the death of her family’s carefully constructed kingdom and legacy. Fortunately, Larraín and Portman remember that Jackie was also a human being, and they render her convincingly in a complex portrayal.

Jackie served as First Lady during her husband’s brief years as President of the United States of America. During that time, she played a major role in establishing a national identity for the presidency by instilling the notion that her family was the People’s Family. In 1962, she famously invited America into her newly reconstructed and redecorated White House, insisting that, because they were the First Family of the U.S., they should have nothing but the finest art, sculpture, and furniture around them. “I just think that everything in the White House should be the best,” she said. Portman captures Jackie’s elegance and oblivious elitism in all its many complicated facets. Speaking of the surface layer, do yourself a favor and visit YouTube to watch Jackie’s televised White House tour. It may be difficult to appreciate just how well Portman mirrors Jackie’s wooden onscreen mannerism, her breathy manner of speaking, and her slight lisp—quite intentionally making it all seem like a very practiced performance.

In another film, the artificial quality of Portman’s acting may seem transparent, but in Jackie, she’s playing someone with a measured and labored-over public image. In real-life, Jackie was playing many roles as a Kennedy and a President’s wife, but also just a person, complete with her rigid and stately posture offset by her trendsetting personal style. She sought to create a link between royalty and the presidency that seems contrary to American anti-monarchy political ideals, but it was nonetheless something Americans responded to with admiration. In this regard, Jackie understood that linking the present to the past could impart a legacy. The impetus behind her White House decorations and acquisitions linked her family with the Lincolns and Washingtons of the past. “Objects and artifacts survive for far longer than people,” she explained in her tour. “They represent history, identity, and beauty.” Through her manipulation of artifacts and history, Jackie created a lasting association between her husband and the great Presidents before him.

Perhaps this is why, just a week after her husband’s assassination, when the film finds Jackie living on the family’s Hyannis Port, Massachusetts estate, and she has been dejected from the home she built to make way for the Johnsons, her grief has a touch of anger. In the film’s connective tissue, Life magazine journalist Theodore H. White (Billy Crudup) interviews her and insists his article will be her version of what happened in Dallas. To be sure, Jackie has complete control over the interview, saying “I don’t smoke” as she takes a drag of her cigarette. But her broken mental state takes the interview in wandering directions, just as the film meanders through Jackie’s memories. “Nothing’s ever mine, not to keep,” she says, embittered and broken, thinking about the quick turnaround from one First Family to the next, but also her husband. And every time she says something the American people may not want to hear, her interviewer already knows that it won’t make the finished article.

Screenwriter Noah Oppenheim previously wrote adaptations of The Maze Runner and Allegiant, but his script for Jackie, not based on any credited source material, is something else altogether. The screen story jumps around inside Jackie’s post-traumatic mind, remembering moments from her tour under the guidance of her assistant (Greta Gerwig) and designer (Richard E. Grant). We see the assassination’s aftermath and Jackie holding her husband’s open head in her lap, and then the subsequent day in which she continued to wear her blood-soaked clothes. She was also forced to stand by as Lyndon B. Johnson (John Carroll Lynch) was sworn-in on Air Force One. Arguments with Bobby Kennedy (Peter Sarsgaard) and Jack Valenti (Max Casella) over the ostentatious funeral procession that echoed Lincoln’s interment ensue, while Jackie questions what any of it means with her priest (John Hurt). And there is a great pair of scenes that reflect each other: one of Jackie in the mirror, putting on makeup before arriving in Dallas; the other shows her wiping her husband’s blood from her face.

Screenwriter Noah Oppenheim previously wrote adaptations of The Maze Runner and Allegiant, but his script for Jackie, not based on any credited source material, is something else altogether. The screen story jumps around inside Jackie’s post-traumatic mind, remembering moments from her tour under the guidance of her assistant (Greta Gerwig) and designer (Richard E. Grant). We see the assassination’s aftermath and Jackie holding her husband’s open head in her lap, and then the subsequent day in which she continued to wear her blood-soaked clothes. She was also forced to stand by as Lyndon B. Johnson (John Carroll Lynch) was sworn-in on Air Force One. Arguments with Bobby Kennedy (Peter Sarsgaard) and Jack Valenti (Max Casella) over the ostentatious funeral procession that echoed Lincoln’s interment ensue, while Jackie questions what any of it means with her priest (John Hurt). And there is a great pair of scenes that reflect each other: one of Jackie in the mirror, putting on makeup before arriving in Dallas; the other shows her wiping her husband’s blood from her face.

Larraín helms his first English-language feature, his third release of 2016 after The Club, about four condemned priests, and also Neruda, another biopic of sorts that was a hit at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival. None of these pictures resemble one another, but they each demonstrate a filmmaker in control of his artistry, which has been given over to the subject matter. Producer Darren Aronofsky, who has been developing Jackie for several years with his Black Swan star in mind, hand-selected Larraín and much of the talent involved. Shooting on Super 16 film stock for a frame filled with fuzz and grain, cinematographer Stéphane Fontaine pears into the titular subject with penetrating close-ups and frenzied wide lenses, making much of the film look like a 1960s home movie. Editor Sebastián Sepúlveda cuts the scenes into a fragmentary arrangement, adopting the mindset of someone still in shock over the events of the previous week. Nonlinear though the construction may be, Jackie’s themes remain palpable.

An overarching theme in Jackie involves Richard Burton’s Broadway performance of the musical Camelot, which Jack listened to regularly before bed, Jackie explains. She likens her husband to a king and the Kennedys to a royal family. “There will never be another Camelot,” she tells her interviewer. “Not another Camelot.” Perhaps she’s right. It’s difficult to imagine another American political figure being as beloved as JFK; then again, it’s difficult to imagine a First Lady wielding the power of image and history as thoroughly as Jackie did. Of course, the Kennedys marked the first time a presidential family was on display on televisions in every American home. That novelty was cherished, exalted, consecrated by time, and will never return again. And so, the collapse of her family’s brief realm leaves Jackie paranoid and ruined beneath her meticulous façade. The inherent drama of such lofty heights being toppled inform the grandiose and yet deeply personal trauma of Portman’s excellent performance, and this film overall.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review