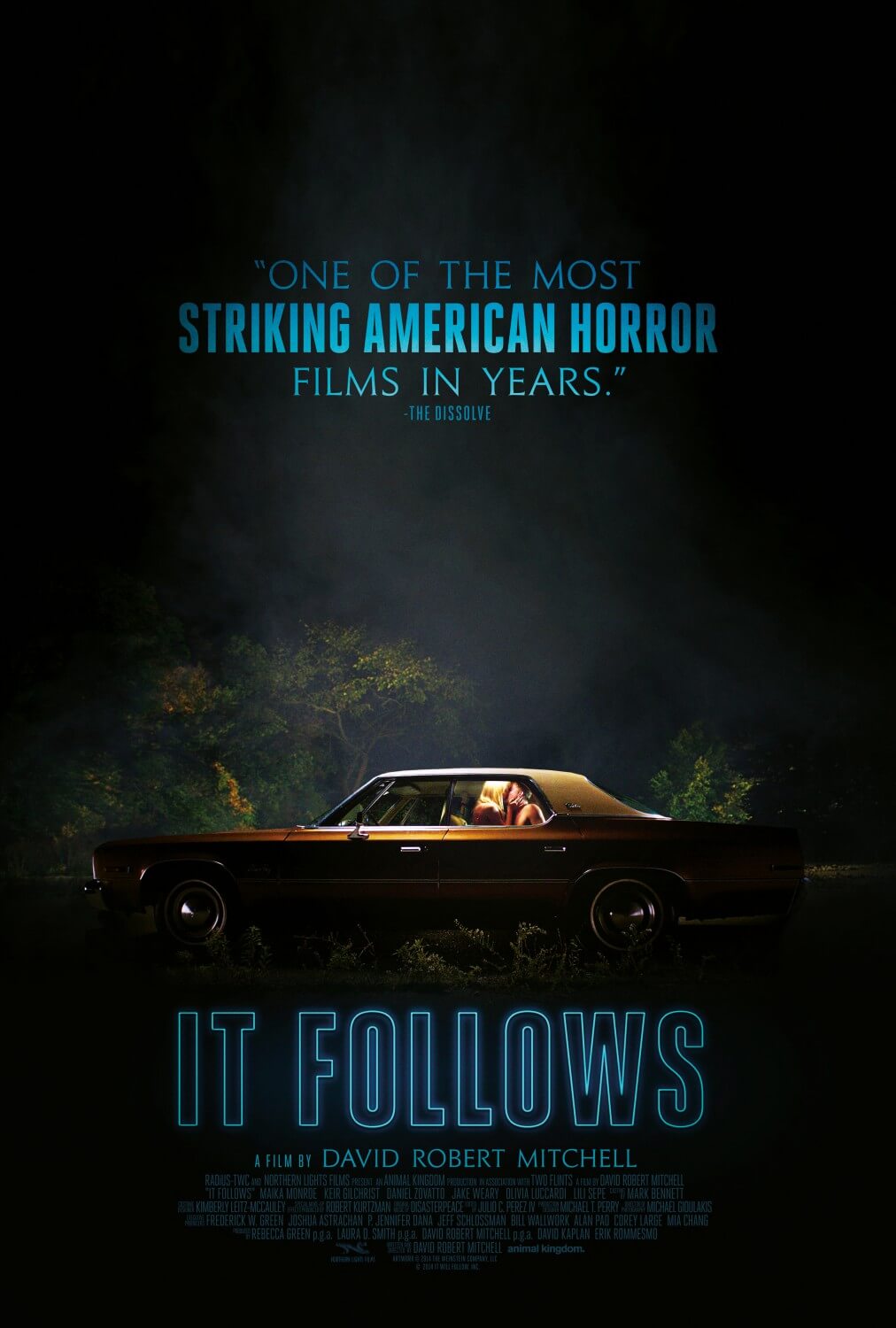

It Follows

By Brian Eggert |

An unnerving sense of dread lingers after It Follows, pursuing the viewer just as the film’s unknown supernatural force stalks its victims. Long after the end credits have rolled, we feel shadowed by an abstract feeling that something approaches—something dangerous and frightening and unstoppable. Maybe the unexplained presence trailing the film’s young heroine at its sluggish pace has somehow walked off the screen and followed us out of the theater. Maybe it will take gradual steps closer and closer, trailing us home until it reaches us and carries out whatever terrible act its visceral needs require. More than once after my screening, this critic considered such a scenario a very real option and found it difficult to decompress. Then again, maybe writer-director David Robert Mitchell has made such a superb horror film that its clinging aftereffect continues for an uncommonly long period.

Mitchell joins Adam Wingard (You’re Next, The Guest) and Ti West (The House of the Devil, The Sacrament) as an independent filmmaker paying homage to the horror films of the late-seventies, early-eighties, specifically those of John Carpenter. Despite having only 2010’s The Myth of the American Sleepover under his belt, Mitchell will henceforth be associated with this small but important collection of talented, independent directors thanks to It Follows. Mitchell’s influences saturate the production, which looks grainy and shot in Carpenter-esque wide angles courtesy of Mike Gioulakis’ lensing. Production designer Michael Perry builds a world that appears to subsist outside of time, where tube televisions glow black-and-white programming in the same world where a seashell-shaped E-reader is no larger than a compact makeup mirror. This juxtaposition of new and old may be fitting, however, since the film takes place in Detroit’s rundown suburbs.

Mitchell’s nod to Carpenter becomes apparent in the first frame. Under Disasterpeace musician Rich Vreeland’s eighties-inflected synth score, the film opens with a master shot of a sleepy residential neighborhood, its streets lined with dead leaves. Instantly, the horror-savvy viewer recalls Halloween (and it won’t be the last time we think of that film either). The appetizer opening tracks a young woman who races out of her home in her pajamas; she looks behind her as if she’s being chased, but we see nothing there. Frightened, she speeds away in her concerned father’s car until she arrives at an abandoned beach. After a while, she sees something there—it’s after her. But she’s been running for a long time, far longer than we’ve seen, and she resolves to give up. Cut to the next morning, when her corpse looks like it was processed in a garbage compactor. What could have done this? The sequence recalls the point-of-view opening in Halloween as a sample of things to come, although the film never manages to be as gory as this prologue.

From here, we’re introduced to Jay (Maika Monroe), a twentysomething young woman living at home with her sister Kelly (Lili Sepe) and their aloof, almost nonexistent mother. Their friends always seem to be lazing around: Paul (Keir Gilchrist), lanky and awkward, carries a torch for Jay; Yara (Olivia Luccardi) reads Dostoyevsky from her aforementioned E-reader while passing gas and chewing on an omnipresent licorice whip; Greg (Daniel Zovatto) is their grungy man-whore neighbor. But we’re immediately drawn to Jay and her brooding, internal quality—the same quality Monroe brought to Wingard’s The Guest. She’s been seeing a young man named Hugh (Jake Weary), and after they finally have sex in the back seat of his car, she finds herself drugged and tied to a wheelchair. Hugh apologizes for what he’s done, but he has something important to show her.

From here, we’re introduced to Jay (Maika Monroe), a twentysomething young woman living at home with her sister Kelly (Lili Sepe) and their aloof, almost nonexistent mother. Their friends always seem to be lazing around: Paul (Keir Gilchrist), lanky and awkward, carries a torch for Jay; Yara (Olivia Luccardi) reads Dostoyevsky from her aforementioned E-reader while passing gas and chewing on an omnipresent licorice whip; Greg (Daniel Zovatto) is their grungy man-whore neighbor. But we’re immediately drawn to Jay and her brooding, internal quality—the same quality Monroe brought to Wingard’s The Guest. She’s been seeing a young man named Hugh (Jake Weary), and after they finally have sex in the back seat of his car, she finds herself drugged and tied to a wheelchair. Hugh apologizes for what he’s done, but he has something important to show her.

What she sees is a middle-aged woman, stark naked, who approaches them at a moderate walking pace. Hugh acknowledges the woman but talks about her like a thing. He explains that when he and Jay had intercourse, he passed something on to her and that, until Jay passes it on to someone else, it will follow her. Though “it” is never overtly clarified, Hugh explains that if Jay fails to elude it, she will be killed. And if she dies, it will begin to pursue whoever gave it to her, meaning Hugh. It can look like people she knows or complete strangers. It appears at times as grotesque figures or seemingly normal people, always walking at that same deliberate pace. There is no way of stopping it. There’s no escape. It just keeps coming, chasing at a leisurely pace after whomever it’s dispatched. Under the surface remains the notion that, no matter how many people pass it on after Jay, it could, in theory, work its way back to her. And so, even after passing it on, there’s no sense of safety for her, ever. The creepy concept alone is simple, yet brilliant.

In time, Jay realizes Hugh wasn’t just some nutjob who tied her up and drugged her; the supernatural threat is very real, and soon Jay’s friends realize this too. They try to escape up to Greg’s cabin, but it follows. They investigate Hugh, which turns out to be a fake name, and it follows. Jay passes it on, but that person doesn’t heed her warning, and soon it’s back after her. They concoct elaborate ways to escape or kill this force, but stopping it is hopeless. No matter what methods they try, it returns like an incurable, consistent case of herpes. Indeed, the film delivers an unquestionable metaphor for the transmission of STDs, how they spread from person to person and never completely go away. They flare up again, or persist in a psychological state of guilt, shame, and anxiety. And under the right circumstances, they become a weapon to be passed to the next victim.

Mitchell controls the pacing, tone, and camera movements with a master’s touch, using tonal electronic music (also Carpenter-influenced) to build a looming sense of anxiety. In one sequence, a tracking shot rotates around a room 360-style and catches the progress of both “it” and its human prey like blips on radar, and the audience squirms for Jay and company to notice it approaching. Mitchell’s use of cross-cutting delivers a similar outcome when he cuts between a stationary future victim and the force’s ever-encroaching progress. But both methods are equally effective at creating suspense. Elsewhere, Mitchell’s camera zooms in on Monroe as she wades in their above-ground pool or lingers in the mirror, probing into the character and building a sense of loneliness, which in turn allows her desire for a human connection to get the better of her. Doubtful Mitchell wanted Jay to be punished for seeking out such a basic human need, but It Follows certainly explores the risks involved in reaching out.

Mitchell controls the pacing, tone, and camera movements with a master’s touch, using tonal electronic music (also Carpenter-influenced) to build a looming sense of anxiety. In one sequence, a tracking shot rotates around a room 360-style and catches the progress of both “it” and its human prey like blips on radar, and the audience squirms for Jay and company to notice it approaching. Mitchell’s use of cross-cutting delivers a similar outcome when he cuts between a stationary future victim and the force’s ever-encroaching progress. But both methods are equally effective at creating suspense. Elsewhere, Mitchell’s camera zooms in on Monroe as she wades in their above-ground pool or lingers in the mirror, probing into the character and building a sense of loneliness, which in turn allows her desire for a human connection to get the better of her. Doubtful Mitchell wanted Jay to be punished for seeking out such a basic human need, but It Follows certainly explores the risks involved in reaching out.

After its debut at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival, It Follows was picked up for distribution by RADiUS-TWC, The Weinstein Company’s subsidiary, for distribution on smaller platforms such as limited theatrical runs and VOD. The film performed so well at early screenings that the Weinsteins resolved to give the picture a wider release. Positive word-of-mouth and high critical reception may expose a larger segment of the mainstream audience to the film, but they may not get its unyielding purpose, which suggests that there’s no possibility for a tidy ending here—which is usually a requirement for crowd-pleasers. This is not a film where an audience will leave feeling safe; of course, a film’s ability to maintain our fear is the mark of an excellent horror film. Like the original Halloween or The Thing, the genuinely frightening cycle of pursuit, not to mention its conceptual genius, continues endlessly and latches itself onto the viewer’s unconscious, and then remains there long after it’s over. Whereas so few horror films today are memorable, It Follows is a scary film that you’ll be hard-pressed to forget.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review