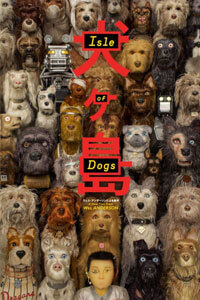

Isle of Dogs

By Brian Eggert |

By now, dogs have figured out that to appear in a Wes Anderson film means death or at least exposure to certain peril. In The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), Owen Wilson’s drugged-up cowboy author madly drove his sports car into the Tenenbaum home, killing their Beagle named Buckley. The family replaces Buckley with an impromptu Dalmatian that probably died shortly after that. In The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), the dog left behind by Filipino pirates had three legs and, alas, its fate was unknown. Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) featured a Beagle put to sleep by poisoned blueberries. Did he ever wake up? Not likely. As for the terrier named Snoopy in Moonrise Kingdom (2012), Khaki Scouts finished him with an arrow. Fortunately, the sole dog in The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) survived; the cat wasn’t so lucky. Perhaps this trend is why the canine actor union staged a protest against Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs, forcing the director to resort once more to stop-motion animation, instead of living dog actors, to tell his story. (No, not really.)

Anderson attempts to make up for a career of doggie displacement with his title, proclaiming “I love dogs,” an oronym that, when discovered, blows the mind. Once again venturing into the fastidiously controlled world of stop-motion animation, where hands move every actor and gesture in just the right way, Anderson labors over design. Isle of Dogs has been lovingly adorned in a million details, and our eyes move about the screen to witness them all, sometimes losing track of the story in the impossible process. Seeing the film twice may be a prerequisite. How appropriate, then, that his film takes place in the Japan of the future, a world envisioned through the director’s understanding of Japanese design principles, as well as his affinity for the films of Akira Kurosawa, paintings of Katsushika Hokusai, and the music of Fumio Hayasaka and Masaru Sato—whose respective scores for Seven Samurai (1954) and Yojimbo (1961) are either used verbatim or influenced composer Alexandre Desplat here.

Anderson wrote the film alongside Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman, and Kunichi Nomura, constructing a scenario comprised of the director’s most familiar narrative tropes: smarter-than-average children who seem wise next to their confused adult counterparts, an elaborate caper whose busy plotting inevitably goes wrong, and characters who descend into contemplative solitude to come out whole. As Courtney B. Vance’s narrator explains, the film spans from Feudal Japan, “before the age of obedience,” to the future’s neo-noir metropolis of Megasaki, where dogs are blamed for a potentially deadly flu outbreak by the despotic Mayor Kobayashi (voiced by Nomura). Should we be suspicious that Kobayashi comes from a long line of cat-lovers? Probably, yes. Kobayashi banishes all dogs to Trash Island, where the exiled canines survive on refuse. Trash Island’s first inhabitant is Spots (Liev Schreiber), the loving guard dog of Atari (Koyu Rankin), an orphaned 12-year-old adopted by his “distant uncle” Kobayashi.

The citizens of Megasaki adapt too easily to the absence of their best friends, except Atari, who flew in a winged jalopy to Trash Island in search for Spots. Instead, the “little pilot” finds a pack of scrappy former house dogs—voiced with proactive aplomb by Edward Norton, Bob Balaban, Bill Murray, and Jeff Goldblum—willing to help. Their leader, a longtime stray named Chief (Bryan Cranston), is a grouchy pooch who warns “I bite” and keeps his distance from the boy, confident that he doesn’t need the love of a human. Fight he does, as evidenced in an altercation between Chief’s pack and a rival group, as they quarrel over garbage in a cottony cloud of arms and tails, recalling Looney Tunes cartoons. To help Atari, the pack heads across Trash Island—a journey set to The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band’s melancholy tune, “I Won’t Hurt You”—picking up clues to Spots’ whereabouts and searching for answers from the wise Oracle (Tilda Swinton) and Jupiter (F. Murray Abraham), the latter of whom interprets the former’s rare dog ability to watch television. Inevitably, over the course of their search, Chief bonds to Atari in a heart melting turn.

Meanwhile, as the story unfolds in a series of chapters, Anderson’s usual detours and asides in the narrative give way to the film’s most inspired moments. Consider the “cannibal dogs” and their sad backstory of lab experimentation and loss, complete with a devastating howl performed by Harvey Keitel. Or Kobayashi’s evil right hand, Major-Domo (Akira Takayama), who arranges for robo-dogs and men with nets to recover Atari and stop him from discovering a dreaded conspiracy. Less interesting, as you might expect, are the human characters, in particular, the underdeveloped American foreign-exchange student, Tracy (Greta Gerwig), a lanky young rebel determined to rescue Atari and expose Kobayashi’s corruption. Anderson’s women often amount to little more than a secondary obscure object of desire for his central male hero (take Chief’s love interest Nutmeg, voiced by Scarlett Johansson, a show dog who doesn’t do much but reluctantly perform tricks). Tracy feels like a superfluous device to propel the plot, whereas our primary emotional investment settles on Atari and Chief.

An active strain of protest against Isle of Dogs had noted Anderson’s appropriation of Japanese culture to suit his film’s requirements. Arguments against the film have noted his failure to subtitle Japanese dialogue, his depiction frowning-faced Japanese men, his dogs speaking American English, and his primary human hero being an American exchange student—altogether creating a sense of Otherness among the Japanese characters. And yet, Isle of Dogs has been lovingly steeped in Japanese cultural influences, revealing Anderson’s apparent Japanophilia. The film features Taiko drumming, Kabuki theater, detailed sushi preparation, cherry blossoms, historical woodblock paintings, and a sumo wrestling match. Kurosawa remains a prevalent resource: when one dog pack faces against another, the scenes echo the showdowns of Yojimbo; the linear procession of heroes on the screen evokes Seven Samurai; the corruption in Megasaki brings to mind The Bad Sleep Well (1960). Are the influences appreciation or appropriation? While Anderson would surely argue for appreciation, this critic found the surface-level Japanese stereotypes distracting at times but never offensive.

Isle of Dogs constructs a world unto itself, derived from a plethora of influences filtered through Anderson’s unique perspective. Competing with The Grand Budapest Hotel as his most fine-tuned work of art direction and design, the film’s mise-en-scène reflects the filmmaker’s interest in surfaces and his knack for building self-contained worlds. Tristan Oliver’s camera captures symmetrical, regimented images centered in the frame, or noticeably off-center as the scene requires, using a color palette of smoky grays contrasted by bold reds, whites, and blacks. Desplat’s inspired score wonderfully approximates its sources with blithe percussions and low, jazzy saxophones from 1960s Japanese cinema. When Anderson’s characters appear on television, they’re amusingly rendered with hand-drawn animation. And there’s always a dark streak to his films, emerging in an assassination, sharp violence, and the pack of former test subjects, now appearing in shambles from missing eyes and limbs to lost sanity. All the while, the viewer must remind themselves that Anderson has created a science-fiction dystopia containing Orwellian notes of cultural suppression and governmental authoritarianism. “Brains have been washed, wheels have been greased, fears have been mongered,” observe Kobayashi’s lackeys at one point, reflecting the film’s potential allegorical undercurrent—Kobayashi’s monumental platform winks at the self-obsessed banner from Citizen Kane (1941).

Admittedly, no review can hope to capture every multilayered facet of Anderson’s meticulous, near postapocalyptic canine world, except to note that Isle of Dogs remains one of his most strange and distinct visions, even if his storytelling isn’t always involving. Through his fetishistic attention to detail, Anderson conceives a work of stop-motion that uses the medium to its fullest by creating a world that could not exist outside of the cinema. But as suggested, it’s perhaps too easy for the viewer to become lost in Anderson’s creativity, as opposed to becoming lost in the emotional power of the storytelling, and so Isle of Dogs feels less engaging than his previous output. Amid the heartening story of a boy and his dog, the intricate animation and humorous deviations keep us laughing (sometimes even sobbing), but more often we’re enraptured in the aesthetics. While the film remains a technical and artistic achievement, its dramatic reach occasionally wobbles, leaving the film impressive but not the usual overwhelming Anderson delight.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review