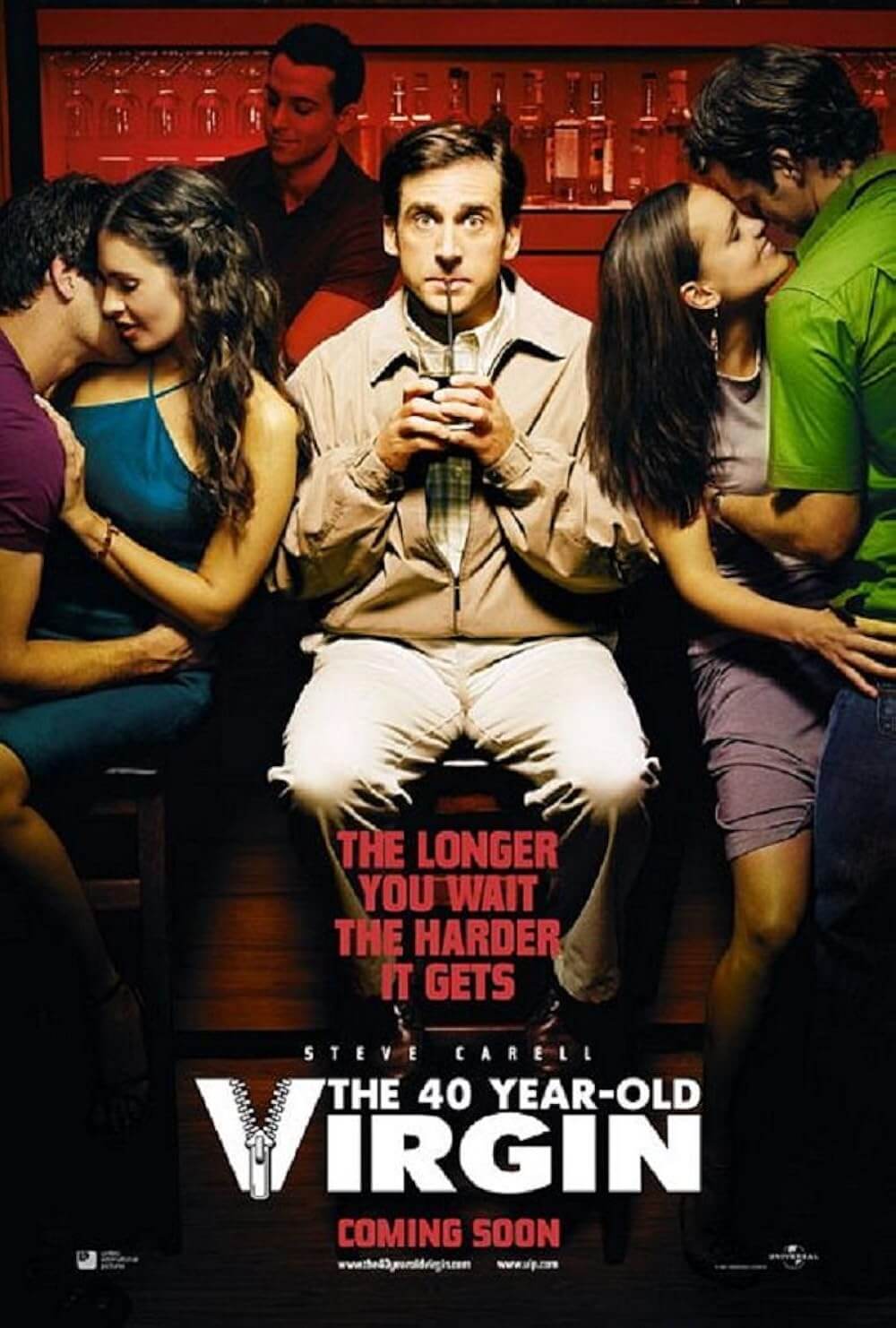

Ishtar

By Brian Eggert |

Writing about Ishtar is a thorny prospect. Or maybe I should call it a difficult problem, a scary predicament, a bitter herb, a dangerous tunnel? The comedy’s reputation as a colossal bomb has followed both the film and its writer-director, Elaine May, since its release in 1987. The title is shorthand for a critical and financial loser. Whenever a comedy goes over budget or will probably result in disaster, it’s common to say, “Well, looks like we have another Ishtar on our hands.” Only in recent years has it undergone reassessment by critics, scholars, and May’s defenders. But after three decades of overwhelmingly bad press, I was surprised to discover that this maligned comedy, often cited among the worst films ever made, isn’t all that bad. Rather, it’s quite good. An unlikely tale of two inept lounge singers caught up in Cold War shenanigans, Ishtar features Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman playing against type in performances that capture May’s improvisational comedy origins. It’s far from the disaster that critics at the time made it out to be, though it’s hardly a misjudged masterpiece either. Then again, it’s easy to fall in love with Ishtar—not unlike the hapless performers played by Beatty and Hoffman, there’s something appealing about rooting for an imperfect underdog.

Curiously, the project started with Beatty feeling indebted to May. She had contributed a sizeable, uncredited rewrite and considerable editing room input to his Oscar-winning Reds (1981), which earned Beatty the award for Best Director. Feeling he owed her, Beatty was determined to make whatever project she wanted, using his clout in Hollywood to make it happen. Her idea was a modern take on Bob Hope and Bing Crosby’s series of Road movies. She imagined a story about two wannabe lounge performers, Lyle Rogers (Beatty) and Chuck Clarke (Hoffman), described as “Simon and Garfunkel’s inbred twins.” Unable to get work in New York (their agent tells them, “You’re old, you’re white, and you’ve got no gimmick”), they accept a gig at a Morocco venue. While there, they get caught up in the untidy relations between the U.S. and left-wing freedom fighters, represented by a CIA official Jim Harrison (Charles Grodin) and a local revolutionary, Shirra Assel (Adjani). Beatty arranged to make the film at Columbia Studios and intended May to have complete control, apart from the title. The film was originally supposed to be called, “The Road to Ishtar,” but Beatty didn’t want to be put up against Hope and Crosby’s reputation.

Many believed the production, which began shooting in October 1985, was doomed from the start. May insisted on shooting in North Africa, in and around the Sahara Desert, where the conflict between Israeli and Palestinian forces had rocked the area with hijackings, killings, and bombings. The area was also littered with landmines, which the production learned about after days of scouting the area. May, a well-known perfectionist filmmaker, took two uncompromising, Oscar-winning actors into a potentially dangerous environment, and she had a blank check to make her film. Looking back, most involved with the production agree it was a recipe for disaster. The overlong production (five months of shooting, ten months of post-production) spent $51 million in Hollywood capital, owing to the difficulty of shooting around Morocco and the difficulty of the principals involved. Everyone wondered why they had to shoot in North Africa, and no one was happy about the extreme heat, least of all May. Unreliable camel wranglers, reports of costly dune-flattening, May’s contentious relationship with Adjani and legendary cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, and the director’s insistence on countless takes made the production a living hell for everyone involved, as detailed in a 2010 article in Vanity Fair by Peter Biskind.

As production costs on Ishtar skyrocketed, the executive leadership at Columbia underwent a changing of the guard. David Puttnam took over for studio chief Guy McElwaine and, as is often the case with transitions at the top in Hollywood, the former administration’s projects became unwanted stepchildren—symbols of a failed management that would often be sabotaged to further articulate that failure. At first, the cost-conscious Puttnam wanted to pull May from the film and replace her. But Beatty, who produced the film, refused to allow that. It didn’t help that, as a producer, Puttnam had made Chariots of Fire, which had competed heavily in the Oscar race against Reds—Puttnam’s film took home four statues, including the Best Picture win, while Beatty’s film took home three. As personalities clashed and power struggles continued in the editing room, May stepped away from the editing process, while both Beatty and Hoffman vied for control over the footage with their own editors. Puttnam resolved to wash his hands of the production; he allowed the chaos to continue, if only to demonstrate that the production was beyond repair. If Puttnam intervened, he could be blamed if Ishtar tanked, but he knew that if he allowed Beatty and May to continue without his involvement, he could absolve himself of responsibility.

By the time the film missed its first release date of Christmas 1986, the press had gotten wind of the troubled production. Some even suspected that Puttnam sought to kill the film by leaking negative stories to the press, as he had been vocal in his criticism of its director (May later called Puttnam “a major putz”). The trades started calling the production “Warrensgate,” linking the film with some monetary scandal of almost criminal proportions. Before it was ever released, the L.A. Times labeled Ishtar “the most expensive comedy ever put on screen,” and the general attitude toward such inflated costs signaled an impending artistic and commercial disaster. To be sure, after additional advertising and distribution costs, Ishtar, which opened in May 1987, would lose around $40 million for Columbia. Though, many involved with the film would later claim the negative pre-release publicity doomed the release. Puttnam supposedly fed ugly details to several magazines, which published pieces about the production’s massive and protracted budget, likening it to another Heaven’s Gate (1980). Taking a cue from the general attitude surrounding the film at the time, critics reviewed the budget rather than the product itself. Roger Ebert, in his half-star review, wrote that May “mounted a multimillion-dollar expedition in search of a plot so thin that it hardly could support a five-minute TV sketch.” Indeed, the negative fervor around Ishtar turned it into a film everyone loved to hate.

May was blamed for the outcome and, to this day, remains exiled from filmmaking. Her career may be one of the most painful examples of someone being welcomed into Hollywood only to be chewed up and spit out again. Her entertainment experience began at a young age in her father’s Yiddish theater group. After dropping out of high school and having a child at the age of 18, she audited university courses and learned about philosophy, comedy, and stagecraft, becoming someone often considered the smartest person in the room. Working her way up from small theater groups in Chicago to New York, she eventually became a regular face on both Broadway and television, where she contributed her barbed sense of humor to both the stage and as a playwright. She became a sensation alongside her school buddy, Mike Nichols, in their widely praised improvisational comedy show, An Evening with Mike Nichols and Elaine May, after it landed on Broadway in 1960. After appearing in a few features, she moved on to directing: the forgotten madcap murder-comedy A New Leaf (1971), in which she starred opposite Walter Matthau; the classic of cruel indecision, The Heartbreak Kid (1972); and Mikey and Nicky (1976), a film wrongfully mistaken as a John Cassavetes picture. She later contributed to the scripts of Beatty’s Heaven Can Wait (1978) and the Hoffman-starrer Tootsie (1982). And though she later wrote The Birdcage (1996) and received an Oscar nomination for Primary Colors (1998), her last feature as a director was Ishtar.

What works about the film is the shared sense of artistic yearning between Lyle and Chuck. They so desperately want to become singer-songwriters, and May gives her actors luxuriously long takes to work out their partnership—scenes filled with the comic rapport between Beatty and Hoffman. Early in the film, they gaze at a New York shop window, looking at records by Simon & Garfunkel and the Talking Heads, but they’ll never be so talented. Their songs, written by May and Paul Williams, may be catchy at times, but their act won’t carry over. Still, there’s something noble about their willingness to endure and keep performing, ever-unaware of where their talent lies on the spectrum. Although they are frequently the butt of May’s humor in the film, Ishtar doesn’t mock or rob these characters of their subjectivity. We cannot help but root for them, though their bickering and stupidity may grow tiresome. By the end, when they’ve resolved to perform their own material instead of tired old tunes like “That’s Amore,” it cheerful rather than groan inducing, despite the winces from the on-screen audience.

While Ishtar turns Lyle and Chuck’s attempt at artistic credibility into the stuff of humor, May uses these daft characters as a platform to address serious issues of the day. Some theories about why the film bombed are quick to note its political message. Ishtar is a movie that, at the height of Reaganism, aligned its heroes with communist guerillas who thwart the CIA’s plans to support the despotic Emir of Ishtar. In doing so, they fulfill a prophecy, telegraphed in an expositional scene early on, about two heroes who humble the mighty to raise up the poor and lonely. The conflict between America’s support of an oppressive regime and the left-wing rebels fighting them initially splits our leading men—Lyle sides with Shirra, Chuck with Harrison. With their friendship split, they learn that neither side proves entirely trustworthy; they’re better off trusting each other. Not only does this realization strengthen the endearing friendship at the center, played with odd couple charm by Beatty and Hoffman, but it reflects a messy political situation unfolding in the Middle East at the time between Afghanistan, Russia, and the United States—which would be Hollywood fodder for years (see Rambo III from 1988). Of course, Spies Like Us covered a similar idea two years earlier. John Landis’ 1985 comedy, starring Chevy Chase and Dan Ackroyd, featured two bungling CIA agents who find themselves in the middle of a plot about the Soviet presence in Afghanistan. Played mostly for cheap laughs, Landis’ movie has none of the feeling found in Ishtar, though it made a whopping $60 million in receipts. By contrast, we want to see Lyle and Chuck succeed, whereas the crass and dopey characters played by Chase and Ackroyd are far less sympathetic.

The humor of Ishtar derives from desperate characters who refuse to separate despite their apparent resentment of one another—they each think they’re the one the other needs more. But they’re both flawed and silly men. I particularly liked Beatty’s stumbling, with Lyle chronically unable to remember lyrics or even perform without his counterpart, whereas Hoffman fits well into the overconfident Chuck. In a more traditionally cast comedy, their roles would be reversed, with Beatty as the cocksure performer and Hoffman as the nervous one. But May’s casting against type enriches the humor. Even so, Ishtar has its fair share of cringe-worthy moments that have not aged well. When Adjani’s character, who dresses like a boy to evade capture, must prove she’s a woman by kissing Lyle or flashing her breast at Chuck in the middle of a busy airport, it feels cheap and forced. Most of the scenes of Adjani’s character seem like plot requirements, not natural developments—which is perhaps why Hoffman clashed with May over the material (the actor proposed that they skip going to Morocco altogether). Likewise, a scene where Chuck pretends to be an Arab auctioneer contains some ugly stereotypes.

By the time machine guns and rockets enter the mix, the film seems to have replaced the singer-songwriter ambitions with a third-act shootout typical of Hollywood films in the 1980s. Still, May’s direction shows an impressive handling of the material, especially given the reports of on-set power struggles and disagreements in the editing room. If the film hadn’t had such a notorious reputation, I would have never guessed it was a troubled production based on the footage. Her other films have a less distinct visual style—a detail indicated by her three cinematographers on Mikey and Nicky, arguably her best film. Still, she works with Storaro to compose some beautiful shots in Ishtar, often employing protracted takes for a more stage-like style in which the actors can improvise, free of today’s impatient cutting. Elsewhere, she shows elegant solutions to standard problems. In a brief flashback sequence, she fades to the past not by using a bar chime—the standard aural indicator of reminiscence—but cuing the change with a familiar ice cream man bell, only to reveal Lyle driving the ice cream truck.

Some have called Ishtar the worst film ever made; by contrast, The New Yorker called it a “wrongly maligned masterwork.” But the film is neither so terrible nor so great. It lingers in the middle-ground somewhere, perhaps even tiptoeing into a belated distinction, if only because such an unfairly discarded film often demands that someone champion it. Hoffman later remarked about Ishtar, “There’s a spine to it: isn’t it better to spend a lifetime being second-rate at what you’re passionate about, what you love, than be first-rate without a soul? That’s magnificent, and that’s what Elaine was after.” It’s a theme that allows the film to transcend its occasional flaws and inescapable reputation. The story’s central friendship, wonderfully played by Beatty and Hoffman as friends who, literally, go out on a ledge for one another, makes everything else in the film seem less important. In a curious parallel, the film’s themes of achieving a sublime form of proud mediocrity mirror the behind-the-scenes story, both marvelously and mordantly so.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review