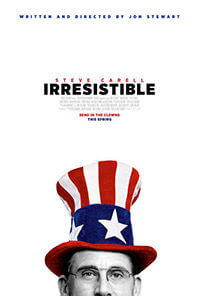

Irresistible

By Brian Eggert |

If Jon Stewart’s first film, the severe Rosewater (2014), about the imprisonment of a journalist in Iran, felt like the work of someone else entirely, then his sophomore effort Irresistible feels more attuned to his political comedy sensibilities established on The Daily Show. The story follows a cynical Washington D.C. strategist trying to find the Democratic party a new candidate from the heartland who will present “a redder kind of blue” to voters. The search takes him to rural America, where he becomes invested in a local mayoral election and discovers a microcosm of everything wrong with our political system. Stewart shrewdly identifies the over-emphasis on data analytics and money mongering that drives American politics, just as he skewers the media that perpetuates unproductive rhetoric. However, his many commentaries emerge in an otherwise messy film of unconvincing characters and broad-spectrum comedy. But the biggest error of Irresistible is that it’s more concerned with making a point than telling a good story.

Steve Carell plays the self-involved Gary Zimmer, who worked on Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2016 and is still spinning from her loss to Donald Trump. Searching for a new Democratic candidate who will appeal to the silent majority, he learns of a YouTube video featuring Col. Jack Hastings (Chris Cooper), a former Marine from Deerlaken, Wisconsin. In the video, this God-fearing, downhome farmer gives a speech at a city council meeting where he defends the presence of immigrants in their small town. Zimmer mobilizes and heads to Wisconsin, where he convinces Hastings to run for mayor against the longtime Republican candidate, Braun (Brent Sexton). He hopes to shed a light on a new kind of Democrat who attends church yet believes in empathy for everyone, regardless of their skin color. The election gains national attention when Zimmer’s competition, the ruthless Faith Brewster (Rose Bryne), brings her skill and Republican dollars to support Braun. Predictably, the two have a history of political and sexual competition, which surfaces in their bawdy exchanges.

Throughout the ensuing campaign, Zimmer behaves like an elitist coastal snob; he’s full of barbed sarcasm and talks down to everyone helping his campaign. Although Hastings and his late-twenties daughter, Diana (Mackenzie Davis), are spared Zimmer’s abuse, the same cannot be said for his data and demographic analysts (Topher Grace, Natasha Lyonne). Stewart’s screenplay uses Zimmer to characterize a strain of the Democratic mentality that preaches empathy yet more often pretends to have empathy as a strategy, and therefore seems rudely superior. Stewart shows that Republicans have become the tyrannical party of the religious right, whereas the Democrats remain twisting in the wind, unsure of what they stand for as a whole. It’s not quite clear what Diana stands for, though, besides a writely device—a symbol for the moral middle ground. She questions the logic of running a dirty campaign that goes almost as low as the Republicans, if only for the “greater good,” and remains at the center of a last-minute twist that teaches everyone the folly of their ways.

Meanwhile, Stewart makes the same mistakes as the Democrats. He can’t decide whether he wants to poke fun at Wisconsinites or show them for being more than Midwestern stereotypes. In one scene, he portrays them as morons who can’t tell the difference between a voter list and an office contacts list. Later on, he shows two locals named Big Mike and Little Mike (Will Sasso, Will McLaughlin) having a smart conversation about the media’s complicity in creating entertainment rather than critical thinking journalism. He acknowledges that Democratic campaigns usually end up isolating swing states by pandering to the liberal base (“To flatter them, you have to condescend to us,” Diana observes), but then Stewart makes the same error by putting Midwestern idiosyncrasies at the butt of many jokes. The film tries to dispel some stereotypes—such as when Zimmer attempts to show he’s down-to-earth by ordering “a burger and a Bud,” only to discover later that it’s a Hofbrau house where neither are served. But it plays into other stereotypes for the sake of laughs, including various gags about cows, pastries, and waistlines.

More to the point, Irresistible has an undercurrent of anger about our political system, and it comes pouring out during several speeches and overt statements in the last third. The funniest of them takes place during the end credits, where a group of MSNBC television personalities questions whether the media is responsible for perpetuating a broken system. “Are we framing these stories on an artificial right-left axis because that’s how our pundit economy is set up? Is there a better way to do this?” Crickets from the panel. Elsewhere, Stewart offers multiple false endings where the credits begin to roll, but then stop and start over (refreshingly, one of them is used to poke fun at the inappropriateness of a romance between Zimmer and Diana). This is followed by a where-did-they-end-up recap for various characters, including one that reads, “Money lived happily ever after… reveling in its outsized influence over American politics.” If these examples are any indication, Irresistible is a satirical blunt object. What’s more, most of these points have been made elsewhere, including Network (1976), Being There (1979), and Wag the Dog (1997), three films that have a better tonal consistency to their satire.

Stewart’s direction is all over the place. He offers tender scenes set to Bryce Dessner’s acoustic guitar score, and then he contrasts them with weird flourishes featuring a cyborg supporter (and references to both Jurassic Park and RoboCop in a single shot). Still, Irresistible contains moments of occasional wit and ironic hilarity. Watch an early scene where Zimmer and Brewster talk to the press and openly acknowledge that they’re being lied to (“It’s called spin”), they know they’re being lied to, and they have accepted that they’re being lied to. Keeping things political and purely satirical would have served the message to a sharper effect. Instead, he struggles to create characters who learn valuable lessons and endear us to the story to boost his point. You can feel Stewart scrambling, trying things out, and reaching to wrap up his closing arguments, all while trying to make it feel important. And while it’s easy to agree with everything he feels outraged about, he puts forth his message in such a scattershot way that it fails to resonate.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review