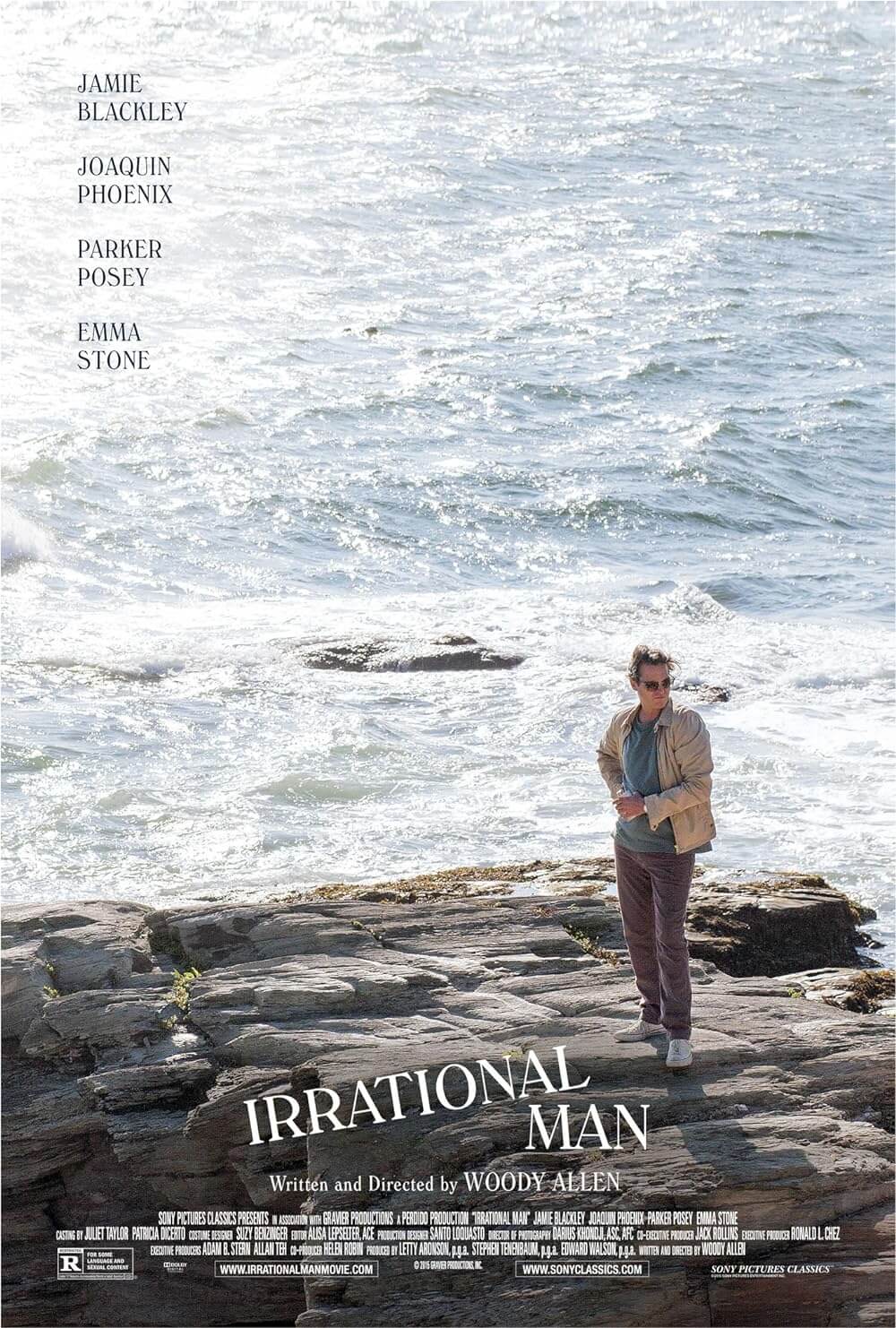

Irrational Man

By Brian Eggert |

Thinking about murder is natural, therapeutic even. Over a drink, friends might deliberate in jest about how to carry out the proverbial perfect murder. There’s a great scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt where a suburban paterfamilias sits down with his neighbor Herb to discuss how they plan to kill one another. When his wife scolds him for such morbid conversation, he replies, “We’re not talking about killing people. Herb’s talking about killing me and I’m talking about killing him.” In Irrational Man, Woody Allen explores the concept of a radical philosophy professor who justifies the ethical implications of murdering a corrupt judge because he determines its positive effect on society results in a moral act. Not unlike Jean-Paul Sartre’s views on the responsibility of freedom, Allen seems to believe that people determine their own moral guidelines—that ethics are a matter of individual conscience. Social and religious structures usually inform moral choices, applying notions of law and sin to our collective conscience; as individuals, we embrace certain rules and choose to abide by them. These structures vary depending on the individual society and, even further, the individual’s own ability to engage in an existential search for answers and then adhere to a unique moral responsibility. The concept goes back to Allen’s longtime perspective that the universe is chaos, and people must find their own purpose somewhere within the bedlam.

“Murder is the most common denominator through history for getting something done effectively,” Allen reportedly mused at a New York City press conference for Irrational Man. “I learned it all from Alfred Hitchcock movies.” Allen’s work has long considered the ease of murder, and his affinity for Hitchcock has been no secret. Films like Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993) and Scoop (2006) both involve characters investigating a murder. But in many of his works, the question of pulling off the perfect murder is not a question of how, not a question of forensics, nor method of choice; it’s a question of whether the murderer can live with their decision. Cassandra’s Dream (2007) follows two desperate brothers (Ewan McGregor, Colin Farrell) who commit a murder together, but only one can live with the decision, which ultimately leads to their doomed end. Match Point (2005), too, considers how getting away with murder is not only a question of conscience, but luck. Easily his best film containing a murder theme, Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989) weighs reality against fantasy, real-life against the “Kingdom of Heaven”, and realism against Hollywood—all in relation to murder and how we perceive the universe as fair or unfair, intentional or chaotic.

Shot on sun-washed days in splendid Panavision widescreen by cinematographer Darius Khondji, Irrational Man begins with the arrival of Abe Lucas, played by Joaquin Phoenix behind a round stomach, greasy long hair, and generally defeated appearance (imagine his Inherent Vice character “Doc” Sportello as an East Coast intellectual). Before Abe arrives at his new summer semester posting at a Rhode Island university, the fictional Braylin College, the campus buzzes with talk of his controversial ideas and books, reputation for philandering with students, and his debilitating depression and drinking. Unhappily married science professor Rita Richards (Parker Posey) has heard about Abe’s exploits and wants a sample, resolutely appearing at his home with a bottle of single-malt Scotch (his favorite) to earn an invitation inside. Bright-eyed student Jill Pollard (Emma Stone), who lives nearby with her parents (Betsy Aidem, Ethan Phillips), has a seat in Abe’s Ethical Strategies class and can’t wait to pick his brain. For Jill, he’s immediately fascinating and sympathetic. She hears stories about his relief work in Darfur and New Orleans after Katrina, how his wife left him for his best friend, and how he witnessed another friend step on a land mine and die in the Middle East.

Shot on sun-washed days in splendid Panavision widescreen by cinematographer Darius Khondji, Irrational Man begins with the arrival of Abe Lucas, played by Joaquin Phoenix behind a round stomach, greasy long hair, and generally defeated appearance (imagine his Inherent Vice character “Doc” Sportello as an East Coast intellectual). Before Abe arrives at his new summer semester posting at a Rhode Island university, the fictional Braylin College, the campus buzzes with talk of his controversial ideas and books, reputation for philandering with students, and his debilitating depression and drinking. Unhappily married science professor Rita Richards (Parker Posey) has heard about Abe’s exploits and wants a sample, resolutely appearing at his home with a bottle of single-malt Scotch (his favorite) to earn an invitation inside. Bright-eyed student Jill Pollard (Emma Stone), who lives nearby with her parents (Betsy Aidem, Ethan Phillips), has a seat in Abe’s Ethical Strategies class and can’t wait to pick his brain. For Jill, he’s immediately fascinating and sympathetic. She hears stories about his relief work in Darfur and New Orleans after Katrina, how his wife left him for his best friend, and how he witnessed another friend step on a land mine and die in the Middle East.

When Abe finally begins his lectures and describes one of Jill’s papers as “original”, he and Jill begin spending time together, platonically. Jill hopes to break Abe out of his funk, while her longtime boyfriend Roy (Jamie Blackley) grows jealous after hearing about how fascinating she finds Abe, noting her emergent infatuation. “He’s a real sufferer,” she swoons. A dejected man, Abe remains obstructed in more ways than one. Formerly addicted to the distraction of orgasms and alcohol, he’s now unable to perform in his inevitable affair with Rita and openly drinks from a flask on campus. Abe also harbors a nasty case of writer’s block, leaving him unable to finish his book (“Just what the world needs,” he quips. “Another book on Heidegger and Fascism.”). When Jill invites Abe to an off-campus student party and one of the youngsters pulls out dad’s pistol, Abe puts a round in the chamber and shows them how Russian roulette is played, much to their horror. Nevertheless, Jill can’t help but find herself drawn to such a complicated man; however, her passes go unreturned. Abe feels he has nothing to offer. Things change when, during a meal at a local diner, Abe and Jill eavesdrop on a woman talking about how she’s fated to lose her ongoing custody case because her ex-husband knows the corrupt judge. Abe and Jill proceed to have one of those hypothetical conversations about how much better the world would be if someone killed the judge.

In true existentialist form, Abe has already resolved that “much of philosophy is verbal masturbation,” and what has that ever cured? Thinking will provide no solution; only doing can help him. His own activist efforts in Darfur and New Orleans had no profound consequence given their scope, but ridding the world of an unethical judge is a solitary, “meaningful” act that would have major implications on the betterment of the world. Not knowing the judge in any personal or professional way, he would never be a suspect; with no obvious motive, he could actually fulfill that long-sought ideal of The Perfect Murder. And so, Abe resolves to carry out a plot involving cyanide, the judge’s ritualized morning cup of juice after a jog, and a switcheroo on a park bench. Somehow, Abe gets away with it, even if he’s initially quite shaken and on the verge of tears. But soon he’s overcome by an all-encompassing sense of purpose. His affair with Rita proceeds splendidly. “You were like a caveman,” she praises. “What happened to the philosopher?” He stops drinking. He smiles and laughs. He now disregards Sartre’s famous quote from No Exit, “Hell is other people,” and embraces simple pleasures like food and the smell of fresh air. Abe even indulges Jill in a romance, while Rita and Roy are tossed aside (“We never said we were exclusive,” Jill claims). Even the music around Abe shines; Allen chose Ramsey Lewis Trio’s lively jazz instrumental “The ‘In’ Crowd” to play throughout the film to echo Abe’s new sense of purpose.

In true existentialist form, Abe has already resolved that “much of philosophy is verbal masturbation,” and what has that ever cured? Thinking will provide no solution; only doing can help him. His own activist efforts in Darfur and New Orleans had no profound consequence given their scope, but ridding the world of an unethical judge is a solitary, “meaningful” act that would have major implications on the betterment of the world. Not knowing the judge in any personal or professional way, he would never be a suspect; with no obvious motive, he could actually fulfill that long-sought ideal of The Perfect Murder. And so, Abe resolves to carry out a plot involving cyanide, the judge’s ritualized morning cup of juice after a jog, and a switcheroo on a park bench. Somehow, Abe gets away with it, even if he’s initially quite shaken and on the verge of tears. But soon he’s overcome by an all-encompassing sense of purpose. His affair with Rita proceeds splendidly. “You were like a caveman,” she praises. “What happened to the philosopher?” He stops drinking. He smiles and laughs. He now disregards Sartre’s famous quote from No Exit, “Hell is other people,” and embraces simple pleasures like food and the smell of fresh air. Abe even indulges Jill in a romance, while Rita and Roy are tossed aside (“We never said we were exclusive,” Jill claims). Even the music around Abe shines; Allen chose Ramsey Lewis Trio’s lively jazz instrumental “The ‘In’ Crowd” to play throughout the film to echo Abe’s new sense of purpose.

All the while, Abe preserves the secret to his newfound joys. And rather than his conscience causing him to unravel, he savors his renewed sense of purpose and confidently navigates the casual suspicions of others. First Rita, who playfully suggests Abe killed the judge because someone spotted Abe in the early morning (Abe is not a morning person), which was when the judge was murdered. During a dinner with Jill’s parents, he secretly gloats as the murder becomes the topic of conversation. The dynamic in this scene cannot help but resemble the familial, yet sexual tension between Uncle Charlie the murderer and his suspicious niece Young Charlie in Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt. Except, it would be a mistake to label Abe a sociopath like Uncle Charlie; rather, a desperate philosopher whose own devotion to a school of thought has at once healed and condemned him. Until the end of Irrational Man, Abe remains sympathetic, if not lost. He begins as an unloved, purposeless intellectual, withdrawn from existence because he finds it futile. After the murder, he no longer despairs over his existence; things like a hearty breakfast make him smile. Opposite Abe, Jill remains wrapped up in life, learning about it, especially the romantic idea of Abe’s former existential pit in which everything disappears. But these romantic ideas are just that, and her impressionable studiousness has a long way to go before reaching Abe’s scholarly level of cynicism and malcontentment before he made his breakthrough.

The clues continue to tally up, and soon Jill confronts Abe about her suspicions. He admits his crime only to discover that her hypothetical moral position on the judge was just talk, and that in reality, the idea of murder devastates her. Of course, in an intellectual argument, Jill cannot debate Abe’s logic. But she feels that what he’s done is wrong. Stone is excellent in her scenes of confrontation; her quiet charm becomes intense emotional distress and the panic of a broken heart. Phoenix, meanwhile, retains the contented calm of a man who knows just where his happiness lies, and he’s coolly suited to the role. To be sure, just as Abe could articulate his earlier melancholy and do nothing about it, he’s profoundly satisfied with his act of murder. After all, Abe is a feeling creature despite his intellectual approach to life; now that the two are in unison, he couldn’t be happier. Jill finally warns that unless he turns himself in, she will go to the police herself. On the outside anyway, Abe agrees, but meanwhile resolves to do away with her. Just as he did the judge, he follows her routine. He waits after her piano lesson outside of an open elevator, the shaft of which he has assured is empty. When Jill arrives, Abe tells her that he wants her to walk him to the police station. As the elevator door opens to an empty drop, he tries to push her down; but during the struggle, he slips (ironically, on the flash light he won for her at the fair), and falls to his death.

The clues continue to tally up, and soon Jill confronts Abe about her suspicions. He admits his crime only to discover that her hypothetical moral position on the judge was just talk, and that in reality, the idea of murder devastates her. Of course, in an intellectual argument, Jill cannot debate Abe’s logic. But she feels that what he’s done is wrong. Stone is excellent in her scenes of confrontation; her quiet charm becomes intense emotional distress and the panic of a broken heart. Phoenix, meanwhile, retains the contented calm of a man who knows just where his happiness lies, and he’s coolly suited to the role. To be sure, just as Abe could articulate his earlier melancholy and do nothing about it, he’s profoundly satisfied with his act of murder. After all, Abe is a feeling creature despite his intellectual approach to life; now that the two are in unison, he couldn’t be happier. Jill finally warns that unless he turns himself in, she will go to the police herself. On the outside anyway, Abe agrees, but meanwhile resolves to do away with her. Just as he did the judge, he follows her routine. He waits after her piano lesson outside of an open elevator, the shaft of which he has assured is empty. When Jill arrives, Abe tells her that he wants her to walk him to the police station. As the elevator door opens to an empty drop, he tries to push her down; but during the struggle, he slips (ironically, on the flash light he won for her at the fair), and falls to his death.

Regardless of how much Irrational Man has in common with Allen’s other, celebrated tales of murder, critics were particularly harsh in their assessments. Several critics accused Allen of “self-parodying” and lamented the shifts in tone from lightheartedness to serious unease to suspense. Many critics attacked Allen’s exploration of existential themes he’s treaded before. Manohla Dargis at the New York Times equated the film to an “existential shrug”. Chris Nashawaty at Entertainment Weekly wrote “Woody Allen has always repeated the same handful of themes in his films, but now even his repetitions are getting repetitious.” This kind of assessment seems illogical and angry, as it accepts that Allen dwells on the same ideas but then condemns him for it. Would one blame the late Ingmar Bergman for making yet another film about the search for answers, or Quentin Tarantino for putting his spin on an established genre? Indeed, many critics seemed fed up with Allen’s ideas and themes in their reviews, specifically his habit of casting an older man opposite a younger woman romantic interest, about which Amy Nicholson of L.A. Weekly wrote, “Finally, Allen is aware that his May-December romances are preposterous and naive.” But this is less an Allen trait than a Hollywood one (titles from 1957 and 1963, Love in the Afternoon and Charade, come to mind). The consensus was Irrational Man was classic Allen, but critics were tired of classic Allen—they were more interested in seeing something fresh like Midnight in Paris (2011) or Blue Jasmine (2013).

Harsh and occasionally thoughtless reviews notwithstanding, the film contains a few inelegant choices by the writer-director. Structurally, Irrational Man employs Allen’s oft-used device of narration to curious effect. Like the prose in a novel, we hear both Jill and Abe’s inner thoughts about one another and about the murder; these sound more like recollections than by-the-minute commentary. The best and most functional narration follows the form of the piece. For example, in Double Indemnity, Fred MacMurray’s character delivers his narration into a tape recorder that will serve as his confession. Irrational Man offers no such device within the film, and the narration proves even less rational once we arrive at the conclusion when Abe falls to his death. But perhaps the didactic quality of the film and its exploration of philosophical ideas negates any need to apply logic to the voiceover. Moreover, this is easily one of Allen’s least accessible films, with brief references to Simone de Beauvoir, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Immanuel Kant, and several other influential thinkers. If viewers are unfamiliar with their works, they may remain on the outside looking in at Allen’s discussion about the difference between philosophy and real-life implementation. This no doubt contributed to detractors calling the film “pretentious”.

Harsh and occasionally thoughtless reviews notwithstanding, the film contains a few inelegant choices by the writer-director. Structurally, Irrational Man employs Allen’s oft-used device of narration to curious effect. Like the prose in a novel, we hear both Jill and Abe’s inner thoughts about one another and about the murder; these sound more like recollections than by-the-minute commentary. The best and most functional narration follows the form of the piece. For example, in Double Indemnity, Fred MacMurray’s character delivers his narration into a tape recorder that will serve as his confession. Irrational Man offers no such device within the film, and the narration proves even less rational once we arrive at the conclusion when Abe falls to his death. But perhaps the didactic quality of the film and its exploration of philosophical ideas negates any need to apply logic to the voiceover. Moreover, this is easily one of Allen’s least accessible films, with brief references to Simone de Beauvoir, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Immanuel Kant, and several other influential thinkers. If viewers are unfamiliar with their works, they may remain on the outside looking in at Allen’s discussion about the difference between philosophy and real-life implementation. This no doubt contributed to detractors calling the film “pretentious”.

The discussion, Allen’s thoughtful application of philosophic theory into narrative, remains the central, edifying device in this film. For example, rather than conclude that Abe is the titular “irrational man,” consider instead the title’s origin, a 1958 text by philosopher William Christopher Barrett, which explains existentialism in Layman’s terms. Allen’s film does much the same and considers the dangers of murder, getting lost in philosophical thought experiments, and then applying them to real-life scenarios. Simone de Beauvoir would argue that freedom is meaningless without responsibility, but Abe feels a sense of responsibility in what he determines to be the morally right decision to murder the corrupt judge. And without a god (Allen has long been a religious skeptic), Abe finds himself content to act out his morally questionable decision—certainly not to the extreme of Dostoyevsky’s view on religious morality, or lack thereof (“If there is no God, everything is permitted,” Dostoyevsky wrote). Abe’s own atheism is addressed quite simply: “How comforting that would be,” he says of religion. But he still believes in morality, in a sense. And perhaps because his first murder is just, he gets away with it. However, his second attempt at murder, to quiet Jill and protect himself from prison, remains unjust and selfish, and ends with his own death in one of Allen’s little ironies.

Woody Allen’s frequent, career-long discussions about the dance between the chaotic and designed structures of existence have an intentionally collegiate stage in Irrational Man—as the Barrett-derived title indicates. Presenting philosophical ideas to his Layman audience, Allen leaves us with much to contemplate after the final scenes. And while critics noted how the film’s shifts in tone can sometimes be challenging, Hitchcock’s maneuvers between humor and the macabre were often equally challenging for viewers (see Rope, 1948, or the often funny Strangers on a Train, 1951). Yet, such tonal shifts are common in any Woody Allen film because, as an enduring post-modernist, he has always tried to deconstruct our understanding of a thing, be it romance, memory, tragedy, nostalgia, artistry, melancholy, or cinema itself. Irrational Man encompasses everything it means to be a Woody Allen film in that sense, as well as more obvious qualities: breezy dialogue, witty asides and observations, and genre playfulness. But the more Irrational Man forces us to ponder the existential nature of murder and morality, the more Allen’s thematic discussion branches into larger existential questions. And if the film ends on a trifle-of-a-moment, perhaps this is Allen’s way of exacting vengeance in favor of what Sartre said about how “existence precedes essence”—or in other words, the life of the mind is no place to live. Identity is forged in the mind and implemented in life. As for Abe, at least he practiced what he preached. But when he stopped, he paid for it.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review