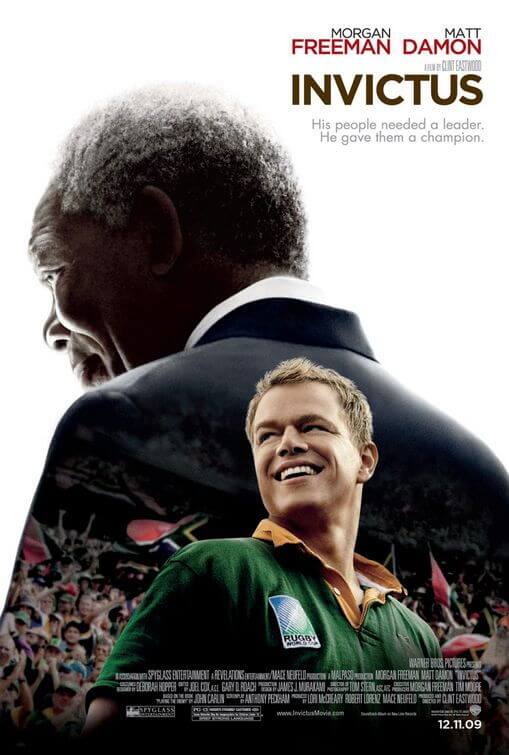

Invictus

By Brian Eggert |

Clint Eastwood films are like a lightly salted, pepper-dusted steak cooked on the grill at a backyard barbecue. It tastes entirely fine; it’s expertly cooked just the way you like it, but it’s one piece of meat that doesn’t have the finesse of something by an artistic chef. That’s not to suggest Eastwood isn’t an artist. He absolutely is. But he’s an artist that relies on subtlety and patience; his safe stories are told with temperance and nuance, and rarely do they challenge the viewer because of the way they’re told. Not to mix metaphors, but he’s a carpenter, a craftsman. It’s doubtful his steaks taste anything like those of Bobby Flay or other grillmasters.

So when thinking about Invictus, it’s easy to praise the film that Eastwood has made. He’s directed another powerful, emotionally stirring drama with his personal touch—the style of a master filmmaker who has honed his craft over a long career. Almost every note hits just as it should, evoking just the right emotion. His camerawork is level, well-blocked, and far from dynamic. Scenes play out just as we expect them to, but the formula is overlooked because of the unique setting and impressive circumstances therein—and because Eastwood lends them particular workmanlike excellence.

Eastwood tells the story of how Nelson Mandela (Morgan Freeman), after his release from prison and election to the president when South Africa’s apartheid fell, took a personal interest in his country’s rugby team, the Springboks. With the white Afrikaners no longer in power, Mandela opts not to dissolve their longstanding rugby team, and instead, he helps unite the white and black members of his divided country by creating a common interest. He approaches the Springbok captain, Francois Pienaar (Matt Damon, well cast and played), and insinuates that, despite their low-ranking status, they should attempt to win the Rugby World Cup.

Those of you up on your world sports history know the Springboks won the competition in 1995, although, that South Africa hosted every game in that tourney didn’t hurt their chances (nothing like home-field advantage). Going into Eastwood’s sports movie, there’s never a doubt of who the winner will be—and not just because we know from history who won, but because the conflict and potential for loss never feel tangible within the movie. The story never has a chance to really take off because of course the Springboks win.

What the audience can cling to, then, are the clever ways that Eastwood makes the greater meaning of the rugby game significant. Mandela’s security detail, for example, goes from an all-ANC foursome to being a mixed octet with four white Afrikaner cops who start off hating their president. Mandela does this on purpose, to force the old and the new groups in power to get along, and to encourage forgiveness. The security guard subplot seems insignificant next to the rugby match, but it helps to illustrate the wise Mandela’s understanding of human nature. He forces an uncomfortable situation so that the two sides will ultimately have the same goals. The crowds of South Africans at first are divided, the Africans unwilling to cheer for the Afrikaners’ Springbok team, but soon it becomes impossible not to cheer when their country’s team keeps winning.

While this is all predictable and rather conventional storytelling, using the very schmaltzy formulas that sports movies often specialize in, what keeps the audience attentive is Morgan Freeman’s staggeringly good performance. It simply must be seen. He displays the humanity of Mandela with flawless presence, capturing that sense of rigid sensitivity and patience in every line of carefully spoken dialogue. Here we see a man reborn onscreen. We believe this is the man who spent nearly three decades in a tiny prison cell and came out not a hardened victim of The System, but a kindly saint. This is a part that Freeman was born to play. For years there’s been talk of Freeman in a Mandela role, and indeed the actor had the president’s personal endorsement to represent him onscreen. But for every Mandela project that failed to materialize for whatever reason, a more politically daring picture was passed up for something safe.

Eastwood couldn’t have made a safer Mandela film than Invictus. This is evident in the overlong, cliché slow-motion finale of the Big Game victory, a sequence that seems to drag when it should have us on the edge of our seats, gripping our armrests. Tremendously apparent in every metaphor and dramatic parallel nodding to the sport, the thick sentiment of the film comes dangerously close to ruining the entire experience. And that’s where Eastwood’s distinctive brand of craftsmanship comes in handy, as he retains the dignity of the picture through his class behind the camera. Had another director shot this film, it’s doubtful the result would be as watchable.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review