Reader's Choice

Intolerable Cruelty

By Brian Eggert |

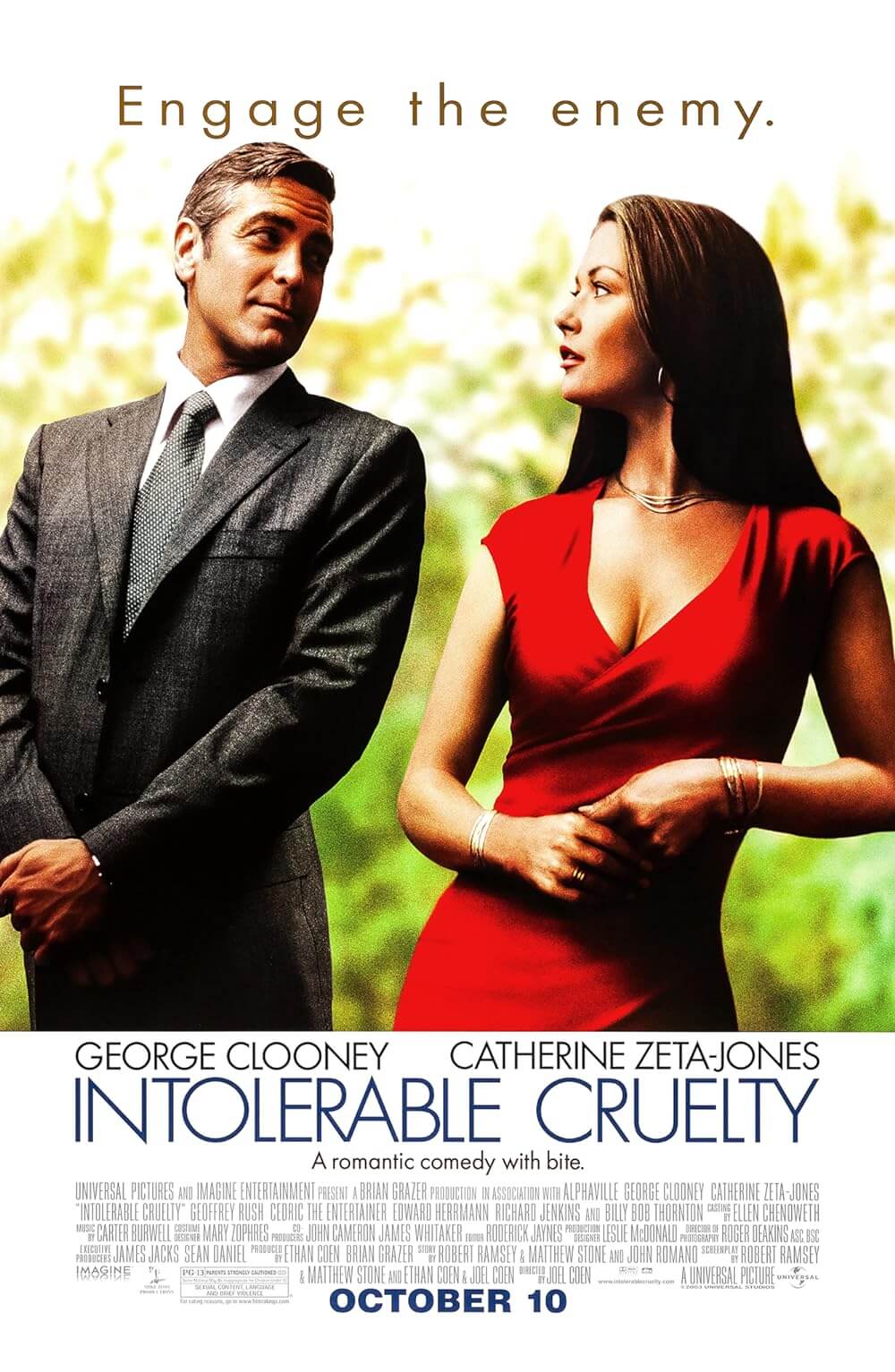

Intolerable Cruelty often takes a place alongside The Ladykillers (2004) as one of Joel and Ethan Coen’s least admired, even dismissible efforts. Compared to much of their other work, the mainstream-friendly result looks light and airy, full of designer clothes, a preponderance of butt jokes, and a stunning cast led by a very smooth George Clooney and an even silkier Catherine Zeta-Jones. On the surface, it looks like a prototypical mainstream romantic comedy packed with weddings, divorces, show-stopping speeches, and a wacky court case whose sitting judge repeatedly declares, “I’m going to allow it.” The uncharacteristically jazzy, larger-than-life score by Carter Burwell seems out of place in the Coens’ oeuvre. And so does the animated opening that shows various cherubs shooting arrows into the hearts of unsuspecting lovers, set to Elvis’ “Suspicious Minds,” a pitch-perfect choice whose lyrics emphasize how the film’s duplicitous characters spend most of their time expecting the worst from their current or future spouses. But like most films by the Coen brothers, Intolerable Cruelty reveals that surfaces can be deceiving. Though it’s about ridiculous Beverly Hills elites who scheme their way into monumental divorce settlements, the characters are intelligent, apart from when their greed or genuine love blinds them. It’s also one of the Coens’ funnier scripts, filled with playful dialogue, ironies galore, and precision plotting.

The film’s reputation is understandable. The project came from an earlier script by Robert Ramsey and Matthew Stone, which was originally planned for directors Jonathan Demme or Ron Howard, whose partner Brian Grazer co-produced. After progress on their adaptation of James Dickey’s 1994 book To the White Sea stalled, the Coens took on this long-gestating project as writers-for-hire, the first of several such arrangements in their otherwise fiercely independent and autonomous career (followed by Gambit, Unbroken, and Bridge of Spies). Among many, the perception was that the Coens had sacrificed their personal signature for a payday, an impression furthered after their remake of The Ladykillers. But the perception of Intolerable Cruelty’s failure is a purely critical one. Commercially, the film’s sheer star power wrangled more than $120 million in box-office receipts, proving for one of the last times in recent history that stars matter. Still, the critic in The Hollywood Reporter called it a “broad farce” and the L.A. Weekly claimed the Coens had “played down to the masses.” Roger Ebert, who thought the opposite was true and felt its humor was too erudite, wrote, “sometimes you just want them to lay off the irony and climb down here with the groundlings.” It seems critics didn’t know if the Coens were elevating lesser material or lowering themselves to commercial fare.

Things appear firmly rooted in the lowbrow in the pre-credits sequence, where Geoffrey Rush plays Donovan Donaly, a television producer who comes home to find an “Ollie’ll Fix It” pool service van in his driveway (Donovan does not have a pool). Inside, he hears scampering feet, his bedsheets appear rustled, and the hair on the back of his wife’s head is frazzled. Though he has grounds to emerge the victor in a divorce settlement, his unfaithful wife (Stacey Travis) has retained Miles Massey (Clooney), a sharp-tongued lawyer who demonstrates his willingness to lie through his newly whitened teeth on behalf of his client. But the Donaly divorce quickly takes a back seat to Miles’ new client, the absurd Rex Rexroth (Edward Herrmann), whose wife, Marylin (Zeta-Jones), has evidence of his infidelity. Marylin’s primary goal is independence, and for that she needs money—she needs to “nail the guy’s ass good,” as her private detective Gus Petch (Cedric the Entertainer) would say. Even as Miles falls head over heels for her, he’s able to expose her gold-digging scheme in court, which sets into motion a series of twists and cons. Marylin’s desire for financial independence becomes ever more scheming—she stages a false marriage to Billy Bob Thornton—while Miles grows increasingly fixated on her (“Obscene wealth becomes you,” he tells her, his eyes twinkling). Both of them question their motives and respective worldviews along the way.

The Coens’ script is a strange compendium of lowbrow humor and the filmmakers’ regular use of witticisms and verbal circularities. Petch’s “nail your ass” routine wears thin, but the playful repetitions and wordplays are a constant source of laughs. The way Miles keeps offering “pastry” at the negotiation between himself and Marylin’s representation, a flabbergasted Freddy Bender (Richard Jenkins) who can’t keep up (in court, Bender objects to Miles’ approach as “arty-farty”), recalls the way a bewitched Tim Blake Nelson repeatedly asks his fellow fugitives in O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) if they “Care for some gopher?” Intolerable Cruelty is also a film of extraordinary names. Take Tenzing Norgay, the Sherpa that helped Edmund Hillary climb Mount Everest in 1915, who Miles references as a metaphor for the people who help others achieve their impossible goals—people who usually have “funny names.” Another such funny name is Baron Krauss von Espy (Jonathan Hadary), a Maurice Chevalier type who directed Marylin toward her first husband (yet another funnily named character, Rex Rexroth). These comical, usually alliterative names are joined by Judge Marva Munson (Isabell O’Connor) and asthmatic hitman Wheezy Joe (Irwin Keyes). Of course, by the final scenes, Marylin’s string of last names becomes a running joke: Marylin Hamilton Rexroth Doyle Massey.

Intolerable Cruelty may be the Coens’ most conventional-looking film. Their versatile cinematographer Roger Deakin shoots the material with gloss and brimming interiors, whereas costumer Mary Zophres dresses Clooney and Zeta-Jones in elegant attire, while everyone else looks either tacky or ridiculous but always brightly lit. Unlike the dominant aesthetic of The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), another unappreciated Coen brothers film drawn from Classic Hollywood archetypes, this film’s formal style takes a backseat to the genre trappings. To be sure, Intolerable Cruelty recalls countless Golden Age screwball comedies—more specifically, the “comedy of remarriage,” a term coined by critic Stanley Cavell in his book Pursuits of Happiness. Cavell argued that Hollywood’s Production Code sought to reinforce moral martial values, but filmmakers wanted to address that married couples often flirt with disaster or engage in extramarital affairs. Since the Code prevented films from showing that some marriages end in divorce, comedies of remarriage—such as Trouble in Paradise (1932) and His Girl Friday (1940)—found couples separating and exploring other sources of romance, only to find themselves back in love with their original spouse by the end. Filmmakers such as Ernst Lubitsch, George Cuckor, Howard Hawks, and Preston Sturges could inject innuendo and thumb their nose at traditional values as long as they restored order by the final scene.

Eventually, Intolerable Cruelty finds Miles and Marylin hitched in a Las Vegas wedding. Both parties have signed the Massey Prenup, an almost mythic document in the context of the film, penned by Miles to eschew any romantic notions of sharing the wealth. But romance is exactly what the prenup allows to flourish (as the saying goes, “Only love is in mind if the Massey is signed”), revealing a romantic at heart under Miles’ distrustful exterior. Miles is the classical besotted mark, duped by Marylin’s beauty and faultless maneuvering. The closest comparison is Preston Sturges’ The Lady Eve (1941), with Zeta-Jones in Barbara Stanwyck’s grifter role and Clooney a stand-in for Henry Fonda’s wealthy but infatuated dope. Both films feature the central couple getting together under the pretense of true love. The woman’s ulterior motive is revealed after her plan proves self-defeating; she has genuine feelings for her naive and endearing gull. The couple reconciles only after admitting their love for one another without any pretense. Intolerable Cruelty deviates from this formula with a decidedly Coen-esque detour into the macabre. When Miles finds himself “exposed” by Marylin’s plan to divorce him and steal his fortune, he hires hitman Wheezy Joe, whose accidental self-inflicted gunshot to the head seems like something that would have happened in a lighter version of the Coens’ debut, Blood Simple (1986).

Those unable to see the Coens’ fingerprints throughout the rest of Intolerable Cruelty need not look further than Miles’ existential dilemma. In the wake of falling in love, he questions his career choices and searches for meaning, just as so many Coen brothers characters—from H.I. McDunnough in Raising Arizona (1987) to Larry Gonick in A Serious Man (2009)—have pondered their existence. As he transitions from money-grubbing divorce attorney to lovestruck target, he’s forced into a cycle of self-reflection and anxiety about his future. When Miles sits in a waiting room to meet with his firm’s senior partner, the vampiric capitalist Herb Myerson (Tom Aldredge) whose lifeblood is the product of failed marriages, he scans over the available reading material. Miles passes over the Harvard Journal of Law and finds a copy of Living Without Intestines, a periodical devoted to rich elderlies who sustain themselves with machines. Miles looks at the centerfold with horror. Is this what awaits him if he continues to thrive on the misery of others? Will he end up like Herb, kept alive by an IV drip of fluorescent green liquid like something out of Re-Animator (1985)? Miles’ ensuing nightmares about Herb as a grotesque monster confirm his dread about leading a life without passion and love.

At the same time, Miles is another of the Coens’ idiotic Clooney characters, one of four (thus far) casting gags played on one of the last true movie stars. As usual, they make Clooney look foolish. Miles first appears in the middle of a teeth whitening session. His dental status is the latest obsession in the Coens’ series of Clooney characters—preceded by his character Ulysses Everett McGill’s preoccupation with “my hair” in O Brother, Where Art Thou?, and followed by his Harry Pfarrer’s need to “get a run in” throughout Burn After Reading (2008) or Baird Whitlock’s quick adoption of the Communist ideology in Hail, Caesar! (2016). Each of these roles features Clooney as a man of some professional or intellectual stature who is reduced by his overestimated sense of Self. Of them all, Miles is most like Ulysses, a word-savvy man who sometimes loses himself in what he’s saying to hilarious effect (Miles begins a self-complement with, “Not to blow my own horn,” mixing idioms). To be sure, Miles has earned a reputation for words, having ruthlessly negotiated on behalf of his clients. For him, compromise is “death” and conquering is “life,” a philosophy that renders him all the more helpless when he falls in love.

Miles’ vulnerability and fear of loneliness are apparent to Marylin, who sizes him up as “bored, complacent, and on the way down.” It’s an astute observation that proves clear to the viewer as well, but not to Miles, whose existential crisis worsens. Love forces him to question his vocation and declare, at a family lawyers’ convention in Las Vegas where he was scheduled to speak about “Nailing Your Spouse’s Assets,” that he’s committing himself to true love and rejecting marital cynicism. It’s the kind of speech that might end a more conventional rom-com, but it’s the catalyst for yet another twist. In a moment of passion, Marylin tears up their prenup. “You’re exposed,” Miles exclaims. But it’s really Miles’ “assets” that are exposed, and Marylin plans to nail them. However predatory Marylin may seem, the Coens humanize her in a scene at dinner, when she confesses the “certain point where you’ve achieved your goals and yet you’re still unsatisfied”—another way of admitting her yearning for a true romantic partner. Watch the way the two characters barely make eye contact, each of them “lost in lonely thoughts,” as observed by critic Adam Nayman. It’s a tender scene that exposes how both of them have become so expert at considering all the angles, but their suspicious minds have left them in a continuous, and lonely, state of doubt.

Whatever Intolerable Cruelty lacks in the Coens’ usual visual richness, it is replaced with slick plotting, attractive stars, and riotous humor. It’s an exchange that might reduce the film to a comparative trifle next to elevated films like Barton Fink (1991) or The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001), except for its lingering commentary about the monetization of marriage. Its rom-com conclusion might seem heartwarming: Miles and Marylin have returned to each other at the last moment before their divorce is finalized. But the film’s coda bristles with the Coens’ auteurist cynicism. The newly alliterative pair of Miles and Marylin have enlisted Rush’s Donovan Donaly to produce a show, America’s Favorite Divorce Videos, suggesting the couple will continue to profit from the marital misery of others. They may have learned to stop trying to exploit each other, but their lesson doesn’t apply to the rest of the world. It’s a development that underscores capitalism’s culture of divorce and greed that the Coens critique with this film, as the show’s host, Gus Petch, compels his enthusiastic crowd to chant “Nail your ass!”—Intolerable Cruelty’s flexible phrase for winning at any cost, even if it means sacrificing your dignity or chances at companionship. Miles and Marylin have found love with each other, but they perpetuate suspicion and the desire to respond to infidelity with revenge, and they profit from the results. Like so many Coen characters, Miles and Marylin have come full circle, though they have learned no great lessons from their experiences in the film, leaving the viewer with a dreary sense of grim inevitability from the otherwise happy ending.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Alex!)

Bibliography:

Baz Allen, William Rodney, ed. The Coen Brothers: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2006.

Cavell, Stanley. Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage. Harvard Film Studies, 1984.

Doom, Ryan P. The Brothers Coen: Unique Characters of Violence. ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2009.

Nayman, Adam. The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together. Harry N. Abrams, 2018.

Rowell, Erica. The Brothers Grim: The Films of Ethan and Joel Coen. The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2007.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review