Into the Woods

By Brian Eggert |

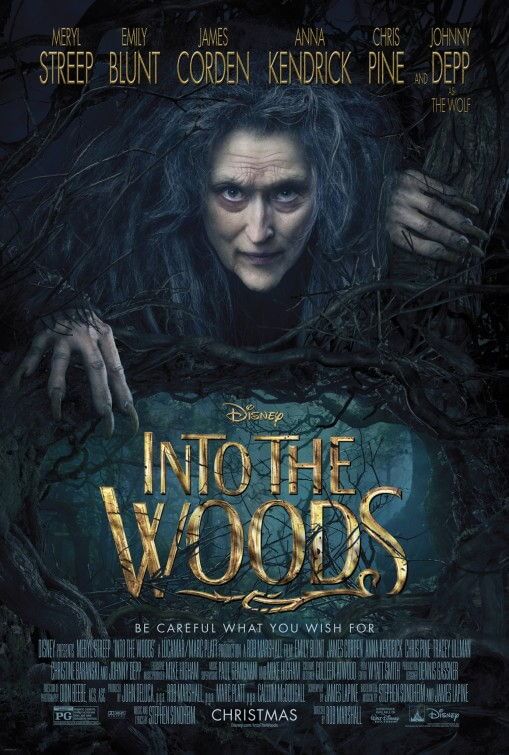

Brothers Grimm fairy tales come to living, singing life in Into the Woods, a long-in-development adaptation of Stephen Sondheim’s Tony Award-winning Broadway musical from 1986. The original and much-celebrated production featured Bernadette Peters and Joanna Gleason in key roles, but Walt Disney Pictures spent a pretty penny ($50 million) on the film and its showy cast: Meryl Streep, Emily Blunt, Anna Kendrick, Chris Pine, and Johnny Depp are just a few of the big names involved. Also showy are the glowing production values, which, in every scene, demonstrate the top-notch skill and visual sense impelling this feature version. Nevertheless, musical purists may feel betrayed by Sondheim and co-writer James Lapine, who have added new musical material and, in some cases, rewrote plot points to satisfy Disney’s family-friendly needs. But therein lies the crucial downfall of such big-screen fare: the filmmakers are so desperate to deliver a universally consumable product (and Oscar-friendly to boot) that the result feels somewhat bland and unfantastical.

The storybook mash-up contains elements from Grimm’s Cinderella, Jack and the Beanstalk, Little Red Riding Hood, and Rapunzel; although, the main throughline revolves around a baker and his wife (James Corden and Emily Blunt). They want to have a child but cannot, as his family has been cursed by a neighboring Witch (Meryl Streep). In order to break the curse, within three days, they must gather a few items for said Witch: a red cape, a golden shoe, a white cow, and some golden hair. So they search for these items in the woods and intersect with characters such as Little Red Riding Hood (Lilla Crawford), the eventually golden-shoed Cinderella (Anna Kendrick), Jack (Daniel Huttlestone) who trades his white cow for the Witch’s magic beans, and the golden-haired Rapunzel (MacKenzie Mauzy). Each of the stories works out as you might expect—according to tradition—but then the story takes several unforeseen turns in the last act, pondering what happens when life doesn’t work out like a storybook.

Talk of an Into the Woods adaptation has stirred through Hollywood since the 1990s, but musicals were out of fashion then and, for one reason or another, it never materialized. Not until Rob Marshall directed Chicago in 2002 and it won the Oscar for Best Picture were musicals chic again. Moreover, Marshall seemed like the perfect choice to champion Sondheim’s musical on film because, along with the lesser Memoirs of a Geisha and Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides to his credit, he’s versed in elaborate productions, and at least a couple of them musicals (Marshall also helmed Nine, but don’t hold that against him; Disney didn’t). With Sondheim closely involved in the adaptation and Marshall directing, the production also boasts three-time Oscar-winning costumer Colleen Atwood, production designer Dennis Gassner, and plenty of special FX to boot. And, Marshall’s cinematographer on Memoirs of a Geisha and Nine, Dion Beebe, brings a showy Tim Burton-esque atmosphere to dark woodlands and old castles, not unlike portions of Alice in Wonderland.

But while laboring over aesthetic details, Marshall and Sondheim’s handling fails to resonate with the same dramatic involvement as the stage rendition did. Indeed, the 2012 version of Les Misérables went through a similar process, where so much attention was given to actors and set-pieces that the narrative took a back seat. What’s more, much too much screen time is spent developing the standard Grimm storylines, whereas Into the Woods doesn’t become novel or really interesting until the final act, when things stop working out in expected storybook fashion (think Enchanted). Moreover, Sondheim’s Disney-ization of his material has led to him toning down the innuendo and death in his story; hints of intercourse in the woods have been modified, and at least one character lives when originally they died. Because the musical’s edgy tone has been reduced, the adaptation feels only just serviceable early on and picks up only when the venerable stories start diverting from their standard trajectories—about three-fourths into the film.

Fortunately, strong casting choices distract from or otherwise enhance the middling treatment of the story. Johnny Depp appears in two brief scenes as Red Riding Hood’s Big Bad Wolf, whose underage sexual proclivities from the stage version have been curbed slightly. Chris Pine appears as Prince Charming, who later pronounces to his significant other that he was raised to be “charming not faithful.” Pine shares the amusing song “Agony” alongside Billy Magnussen, who plays the lesser-defined prince interested in Rapunzel. Christine Baransky, Lucy Punch, and Tammy Blanchard appear as Cinderella’s wicked Stepmother and Stepsisters, all appropriately over-the-top. But the film belongs to Streep and Blunt, whose characters are the most expressive and dynamic in a roster of one-dimensional roles. The Witch and the Baker’s Wife also have the best songs, few of which are truly memorable besides “Into the Woods” and “No One is Alone”.

The long history of Walt Disney mining storybooks for family-friendly motion pictures, animated or live-action, continues with Into the Woods; though, Sondheim’s overall message is far more satirical and grounded than a standard fairy tale. Still, the film version doesn’t feel as playful or revisionist as the stage musical. Those unfamiliar may not notice the differences referenced in this review and, regardless, may find the impressive production captivating and filled with charm in its current state. But those versed in Sondheim’s Sweeny Todd, adapted to expert effect by Tim Burton in 2007, know there’s a comical-macabre streak running through Sondheim’s work that is largely absent here and, as a result, leaves this feeling neutered. And yet, with production values so high and the general pleasantness of the songs and converging, familiar storylines, it’s difficult to find Into the Woods anything but admirable, just not something that deserves wild enthusiasm.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review