Into the Wild

By Brian Eggert |

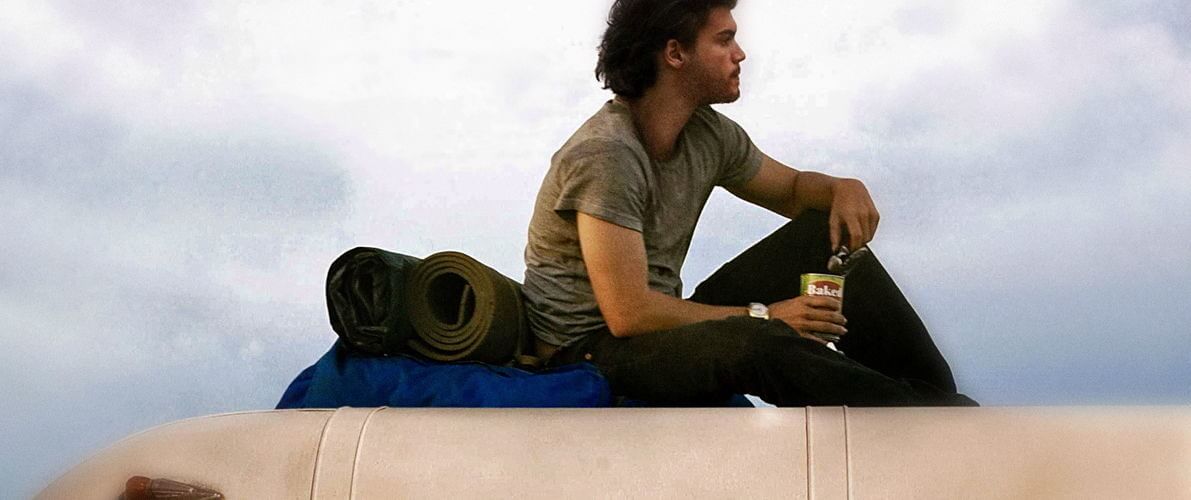

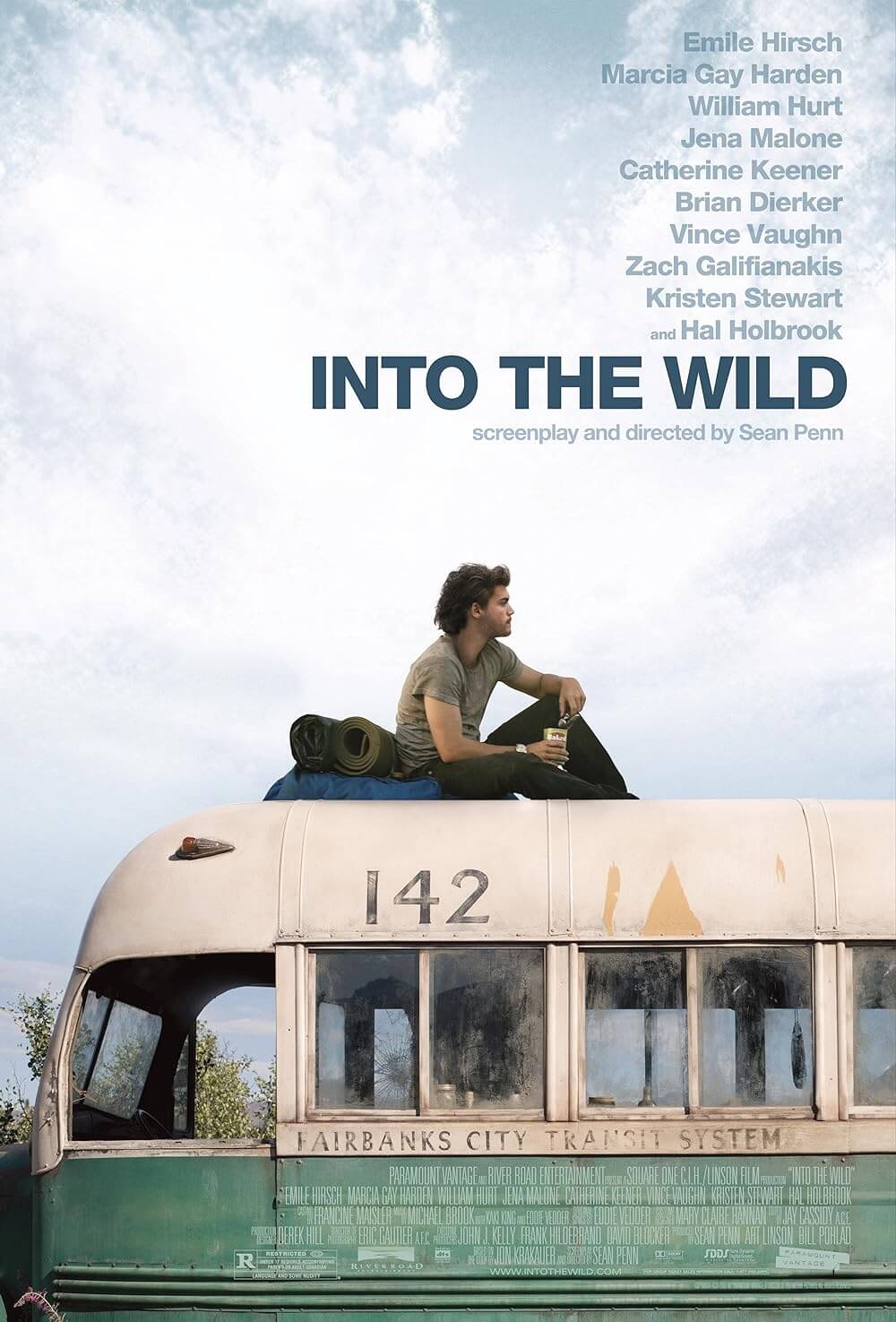

Knowing from the outset that Into the Wild’s existential, holy fool hero Christopher McCandless (Emile Hirsch) reaches his ultimate Alaskan destination instills in us an ever-present sense of foreboding. Since the bulk of the movie depicts his trip there and the personalities he meets along the way, all of whom worry for his wellbeing, Chris’ eventual arrival seems like a victory solely for himself. Based on the acclaimed novel by John Krakauer, Into the Wild grew from the writer’s article published in an Outside magazine article entitled, “Death of an Innocent: How Christopher McCandless Lost His Way in the Wilds.” Sean Penn adapted and directed the screenplay, telling the true story of McCandless’ rejection of “society” as he searches for a more pure way of life, away from injustice and cruelty and civilization in whatever form they may take.

After graduating from college, the idealistic McCandless donates his $24,000 life savings, his law school nest egg, to OXFAM—the organization dedicated to ending famine and poverty worldwide. Ditching his car, Chris sets out on the road, hitchhiking with a purpose and yet with no purpose at all. Guided by Jack London’s novels and survival guides, Chris’ desire to escape is inspiring if naïve. He even creates a new name: Alexander Supertramp, placing himself onto a modern hero pedestal. He rebels against his obtuse parents, who are played by William Hurt and Marica Gay Harden (and are perfectly cast in their roles as out-of-touch narcissists), leaving them and everyone else behind for the road.

The road itself is a symbol that reminds him to remain mobile, which allows him never to question his own actions. He finds brief comforts in friends along the way. Jan and Rainey (Catherine Keener and Brian Dierker) are two aged hippies who seem to recognize that Chris is on a dangerous path. Their concerns are not outspoken, but we see them in Jan’s motherly eyes. Or there’s the elderly Ron Franz (Hal Holbrook), whose old age and wasted life remind Chris why his escape to Alaska is so important. Meanwhile, everyone but Chris himself knows he isn’t coming back.

Pearl Jam frontman Eddie Vedder wrote original songs for the film, accompanied by Michael Brook and Kaki King’s moody, ethereal music. Vedder’s songs are simple ballads, sung with his earthy voice, that flow with the film as they should. They sing to a troubled boy, lost and alone. His sister Carine (Jena Malone) narrates about what she suspects were his motivations, primarily that his parents purported lies and built their family on falsehoods. She feels abandoned, but she understands his quest. For her, Chris’ actions are both catastrophic and necessary. But even out in the world, Chris remains angry, always running and desperate to escape something. Getting away from lies and the people representing them, Chris relies solely on his own sense of survival and on what Nature provides, perhaps not realizing that Nature is just as cruel as humanity. Nature, however, remains innocent, despite its unrelenting brutality, whereas humanity is anything but.

Shot by cinematographer Eric Gautier (The Motorcycle Diaries), Penn’s film is beautifully realized, with full attention to the sublime beauty that Chris loves and respects. Penn is a director who finds beauty in terrible things; his picture The Pledge was one of the most haunting yet attractive movies of 2001. Playing like a dramatized episode of Planet Earth, Chris’ journey places him among deer and on rough rapids and atop high mountains. We understand his desire to see these things, to live, as opposed to enduring what he believes is a decisive preparation for death: a normal life. I couldn’t help but be reminded of Grizzly Man, Werner Herzog’s frightening documentary about a man so misplaced in the world that he can only feel at home when alone with Alaskan grizzly bears. His demise is just as tragic and yet self-effaced as Chris’.

The only absolute statement I can make about Chris is that I respect his determination, although his reasons may have been skewed and planning misguided. I sympathized more with Vince Vaughn’s character Wayne, a farmer Chris meets on his trek, who gives Chris the best advice he can get: to live his life and not think so much. Perhaps when people think too much, they go mad, as it’s what I suspect happened to the real Christopher McCandless. Surely there was an attraction to this story for Penn, whose own Hollywood persona isolated him. Perhaps the once hostile and rebellious Penn saw pieces of himself in Krakauer’s 224-page non-fiction account of McCandless’ journey. Whether Chris found himself, I cannot say, and I don’t believe we can ever really know. So perhaps this is a cautionary tale, a spiritual warning for those who might try to find themselves, to really live. It’s a treacherous world, but escaping from it can be even more dangerous.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review